|

|

- Search

| Ann Geriatr Med Res > Volume 27(1); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

A recent review by Kumari and Khanna examined the prevalence of sarcopenic obesity using various comorbidities, diagnostic markers, and possible therapeutic approaches. The authors discussed the strong impact of sarcopenic obesity on quality of life (QoL) and physical health. In addition, there are significant interactions among bone, muscle, and adipose tissue, and the concomitant presence of osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and obesity, termed osteosarcopenic obesity, represents a terrible trio for postmenopausal women and older adults as each of these conditions is associated with adverse outcomes in terms of morbidity, mortality, and QoL in several domains. Timely diagnosis, prevention, and pro-health education are crucial for improving QoL in patients with osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and obesity. Education and prevention play a pivotal role in the long term for individuals to have longer and healthier lives. Osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and obesity share modifiable risk factors that may benefit from physical activity, a healthy and balanced diet, and lifestyle changes. “Prevention is better than cure” and planning are proven strategies for individuals and sustainable healthcare.

Kumari and Khanna,1) in a recent review, examined the prevalence of sarcopenic obesity using various comorbidities, diagnostic markers, and possible therapeutic approaches. The authors highlighted the strong impact of sarcopenic obesity on quality of life (QoL) and physical health.

Sarcopenia is defined by lower levels of three parameters: muscle strength, muscle quantity/quality, and physical performance as an indicator of severity. Advanced age and physical inactivity are among the main risk factors for osteoporosis2) and sarcopenia.3) The coexistence of these two conditions marks a complex clinical syndrome known as “osteosarcopenia.”

The impact of osteoporosis on the QoL, economic costs, and health burdens is well documented in the literature. Osteoporosis affects 23.1% of women and 11.7% of men worldwide,2) while Clynes et al.4) estimated the global economic burden of osteoporotic fractures to be around $17.9 and £4 billion per annum in the United States and the United Kingdom, respectively.

Frost’s mechanostat theory explains the deep interconnection between the bone and muscle quality and quantity. According to this theory, the mechanical load on the bone affects its quantity (bone mass) and architecture.5) Subsequently, several molecular mechanisms have been identified based on hormonal crosstalk (growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor-1 and gonadal sex hormones), inflammaging (via the ubiquitin-protease pathway and increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-α], interleukin-1 [IL-1], and IL-6), myokines (myostatin) and osteokines (osteocalcin), as well as the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.6) The drugs to treat osteoporosis, including bisphosphonates,7) denosumab,8,9) and romosozumab,10) may also have "double effects" with beneficial effects on both bone and muscle.

Despite evidence of the protective effect of increased body fat mass on bone mineral density (BMD), the "obesity paradox" or "reverse epidemiology" remains controversial.11 Some studies have shown that osteoporosis is associated with lower BMD12); an increased expression of a pro-inflammatory phenotype, activation of the osteoclast-stimulating pathway, infiltration of adipocytes into bone tissue, and increased leptin secretion have explained this detrimental effect. However, higher levels of circulating estrogen and hyperinsulinemia have been reported to be protective against osteoporosis.13) Therefore, understanding the complex interactions between bone and adipose tissue requires further investigation.

A decrease in muscle mass may be accompanied by an increase in fat mass, resulting in a condition called "sarcopenic obesity" or "sarcobesity," in which diseases associated both with obesity (insulin resistance, depression, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension) and sarcopenia (frailty, joint disorders, decreased muscle strength, and reduced functional capacity/disability) have a negative synergistic effect on the individual.1)

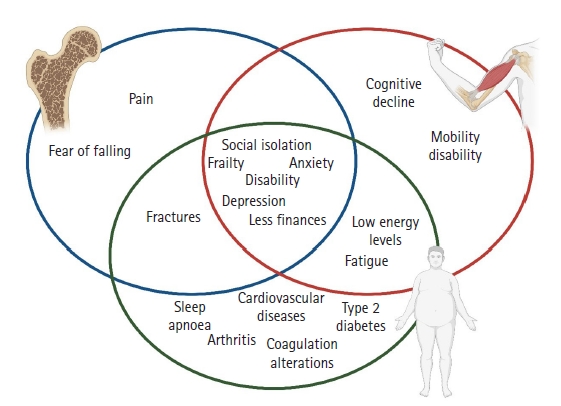

The concomitant presence of osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and obesity, termed “osteosarcopenic obesity,”6) represents a terrible trio for postmenopausal women and people of advanced age as each of these conditions is associated with adverse outcomes in terms of morbidity, mortality, and QoL in several domains (Fig. 1). A cross-sectional retrospective study by Kolbasi and Demirdag14) reported a prevalence of 10.7% in community-dwelling older adults. Perna et al.15) estimated a total prevalence of 6.86% (3.1% in males and 5.4% in females) in a population of older adults. Sarcopenia increases the risk of physical limitation and disability and is associated with a higher risk of falls, cognitive decline, reduced energy, and frailty.3) Increased risk of fractures and hospitalization, loss of independence, pain, functional limitations, fear of falling, and inactivity negatively affect QoL in patients with osteoporosis.16) Obesity increases the risk of coagulation alterations and chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, degenerative articulation disease, cancer, and sleep apnea; it negatively impacts fatigue, energy levels, sleep quality, and rest.17) Finally, all three conditions are associated with social isolation; psychological outcomes such as anxiety, fear, depression, and reduced self-esteem; and negative impact on the environmental domains of QoL, including security, finances, leisure, and information.16-18)

To improve sarcopenia awareness and treatment, the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) updated its definition and diagnostic strategies in 2018 to recommend an updated screening and assessment pathway that is easy to apply in clinical practice.3) A recent study by Prado et al.19) reiterates that screening is the only means to identify individuals at risk of hidden muscle loss and malnutrition. The SARC-F (strength, assistance walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and falls) and the SARC-CalF (strength, assistance in walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs-calf circumference) instruments can screen patients with sarcopenia. Surrogate instruments have been applied to identify low muscle mass in the absence of body composition techniques as not all body composition assessment methods are available in all clinical settings. Calf circumference is an anthropometric measure that correlates well with muscle mass, requires minimal training, and can be used with validated assessment tools within the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) framework to help diagnose malnutrition.20)

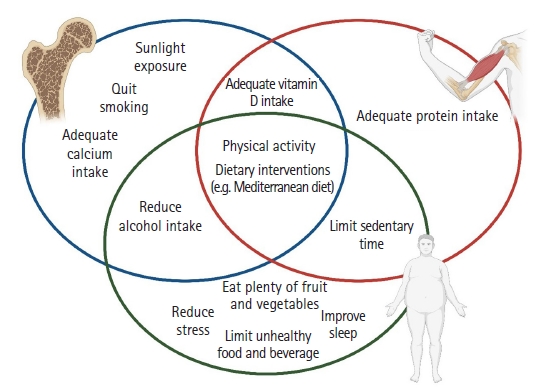

Considering the general aging of the population and the increase in chronic conditions, timely diagnosis, prevention, and pro-health education are crucial for improving health-related outcomes and QoL in osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and obesity. These three conditions share modifiable risk factors (Fig. 2) that may benefit from changes in lifestyle, physical activity, and diet (e.g., health and balanced diets such as the Mediterranean diet).3,6,21-26) It is crucial to follow a healthy, balanced diet that limits the intake of foods high in fat or refined sugars and favors fruit and vegetable consumption to reduce obesity risk. Reducing stress, maintaining good sleep quality, and limiting sedentary time are also components of a healthy lifestyle that may play a role in preventing obesity.21,27,28) High caloric intake due to excessive alcoholic beverage consumption fosters the deposition of excess adipose tissue and can also be a risk factor for the development of osteoporosis. Smoking is also a deleterious habit that can predispose individuals to osteoporosis. The potential measures to prevent bone loss include adequate calcium intake, increased sunlight exposure, and vitamin D intake, which have beneficial effects on sarcopenia.22,29) Finally, dietary interventions and exercise are effective in preventing and treating sarcopenia and physical disability in older people.23)

Nutrition and exercise, parts of a healthy lifestyle, are efficient polypills for improving health outcomes and QoL. Awareness initiatives and education play a pivotal role in the long run for individuals to live longer and healthier lives. As wisdom reiterates, "prevention is better than cure," and planning represents a sure bet for individuals and allows for more sustainable healthcare.

Fig. 1.

Domains of quality of life affected by osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and obesity. Created with Biorender.com.

Fig. 2.

Multi-dimensional interventions to prevent osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and obesity. Created with Biorender.com.

REFERENCES

1. Kumari M, Khanna A. Prevalence of sarcopenic obesity in various comorbidities, diagnostic markers, and therapeutic approaches: a review. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2022;26:296–308.

2. Salari N, Ghasemi H, Mohammadi L, Behzadi MH, Rabieenia E, Shohaimi S, et al. The global prevalence of osteoporosis in the world: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2021;16:609.

3. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyere O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019;48:16–31.

4. Clynes MA, Harvey NC, Curtis EM, Fuggle NR, Dennison EM, Cooper C. The epidemiology of osteoporosis. Br Med Bull 2020;133:105–17.

6. Clynes MA, Gregson CL, Bruyere O, Cooper C, Dennison EM. Osteosarcopenia: where osteoporosis and sarcopenia collide. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:529–37.

7. Harada A, Ito S, Matsui Y, Sakai Y, Takemura M, Tokuda H, et al. Effect of alendronate on muscle mass: investigation in patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 2015;1:53–8.

8. Miedany YE, Gaafary ME, Toth M, Hegazi MO, Aroussy NE, Hassan W, et al. Is there a potential dual effect of denosumab for treatment of osteoporosis and sarcopenia? Clin Rheumatol 2021;40:4225–32.

9. Aryana IG, Rini SS, Setiati S. Denosumab’s therapeutic effect for future osteosarcopenia therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2023 Jan 11 [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.22.0139.

10. Mockel L, Bartneck M, Mockel C. Risk of falls in postmenopausal women treated with romosozumab: preliminary indices from a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 2020;6:20–6.

11. Oliveira MC, Vullings J, van de Loo FA. Osteoporosis and osteoarthritis are two sides of the same coin paid for obesity. Nutrition 2020;70:110486.

12. Chen YY, Fang WH, Wang CC, Kao TW, Chang YW, Wu CJ, et al. Body fat has stronger associations with bone mass density than body mass index in metabolically healthy obesity. PLoS One 2018;13:e0206812.

14. Kolbasi EN, Demirdag F. Prevalence of osteosarcopenic obesity in community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional retrospective study. Arch Osteoporos 2020;15:166.

15. Perna S, Spadaccini D, Nichetti M, Avanzato I, Faliva MA, Rondanelli M. Osteosarcopenic visceral obesity and osteosarcopenic subcutaneous obesity, two new phenotypes of sarcopenia: prevalence, metabolic profile, and risk factors. J Aging Res 2018;2018:6147426.

16. Madureira MM, Ciconelli RM, Pereira RM. Quality of life measurements in patients with osteoporosis and fractures. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012;67:1315–20.

17. Pimenta FB, Bertrand E, Mograbi DC, Shinohara H, Landeira-Fernandez J. The relationship between obesity and quality of life in Brazilian adults. Front Psychol 2015;6:966.

18. Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Arnal JF, Bautmans I, Beaudart C, Bischoff-Ferrari H, et al. Quality of life in sarcopenia and frailty. Calcif Tissue Int 2013;93:101–20.

19. Prado CM, Landi F, Chew ST, Atherton PJ, Molinger J, Ruck T, et al. Advances in muscle health and nutrition: a toolkit for healthcare professionals. Clin Nutr 2022;41:2244–63.

20. de van der Schueren MA, Keller H, Cederholm T, Barazzoni R, Compher C, Correia MI, et al. Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM): guidance on validation of the operational criteria for the diagnosis of protein-energy malnutrition in adults. Clin Nutr 2020;39:2872–80.

22. Uchitomi R, Oyabu M, Kamei Y. Vitamin D and sarcopenia: potential of vitamin D supplementation in sarcopenia prevention and treatment. Nutrients 2020;12:3189.

23. Bernabei R, Landi F, Calvani R, Cesari M, Del Signore S, Anker SD, et al. Multicomponent intervention to prevent mobility disability in frail older adults: randomised controlled trial (SPRINTT project). BMJ 2022;377:e068788.

24. Quattrini S, Pampaloni B, Gronchi G, Giusti F, Brandi ML. The mediterranean diet in osteoporosis prevention: an insight in a peri- and post-menopausal population. Nutrients 2021;13:531.

25. Cacciatore S, Calvani R, Marzetti E, Picca A, Coelho-Junior HJ, Martone AM, et al. Low adherence to mediterranean diet is associated with probable sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults: results from the longevity check-up (lookup) 7+ project. Nutrients 2023;15:1026.

26. D’Innocenzo S, Biagi C, Lanari M. Obesity and the mediterranean diet: a review of evidence of the role and sustainability of the mediterranean diet. Nutrients 2019;11:1306.

27. Volpe SL, Sukumar D, Milliron BJ. Obesity prevention in older adults. Curr Obes Rep 2016;5:166–75.

- TOOLS