Polypharmacy, Potentially Inappropriate Medications, and Dysphagia in Older Inpatients: A Multi-Center Cohort Study

Article information

Abstract

Background

Although the relationship between medication status, symptomatology, and outcomes has been evaluated, data on the prevalence of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) and the association of polypharmacy and PIMs with swallowing function during follow-up are limited among hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years with dysphagia.

Methods

In this 19‐center cohort study, we registered 467 inpatients aged ≥65 years and evaluated those with the Food Intake LEVEL Scale (FILS) scores ≤8 between November 2019 and March 2021. Polypharmacy was defined as prescribing ≥5 medications and PIMs were identified based on the 2023 Updated Beers Criteria. We applied a generalized linear regression model to examine the association of polypharmacy and PIMs with FILS score at discharge.

Results

We analyzed 399 participants (median age, 83.0 years; males, 49.8%). The median follow‐up was 51.0 days (interquartile range, 22.0–84.0 days). Polypharmacy and PIMs were present in 67.7% of and 56.1% of patients, respectively. After adjusting for covariates, neither polypharmacy (β = 0.05; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.04–0.13, p=0.30) nor non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory medications (β = 0.09; 95% CI, -0.02–0.19; p=0.10) were significantly associated with FILS score at discharge.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicated a high proportion of polypharmacy and PIMs among inpatients aged ≥65 years with dysphagia. Although these prescribed conditions were not significantly associated with swallowing function at discharge, our findings suggest the importance of regularly reviewing medications to ensure the appropriateness of prescriptions when managing older inpatients.

INTRODUCTION

Dysphagia is a serious problem in older people that affects aspiration pneumonia and patient quality of life (QOL).1-3) Dysphagia is a disorder caused by the disuse of muscles related to swallowing or impairment of the central nervous system.1) The prevalence of dysphagia varies by setting, with 11%–34% in independent individuals, 29%–47% in inpatients, and 38%–92% in those hospitalized for community‐acquired pneumonia.2) Dysphagia is associated with adverse events, including aspiration pneumonia, dehydration, poor nutrition, and low QOL.1-3) In addition, these adverse events can result in unexpected rehospitalization, prolonged hospitalization, and increased medical costs due to excess medications.4,5) Similarly, side effects and drug-drug interactions can also cause dysphagia.6,7)

Polypharmacy resulting from excessive medication use has been a growing concern among older people in recent years.8-11) Although a consensus definition for polypharmacy is lacking.11,12) several reviews8,13-15) have reported that the prevalence of polypharmacy varies widely (10%–90%) owing to age differences, definitions used, chronic conditions, healthcare settings, and geographical settings. Our previous 21‐center descriptive study16) reported a median of six medications (interquartile range [IQR], 4–7) among 467 hospitalized patients aged ≥20 years with dysphagia. Additionally, several reviews8,10,12,15,17) reported that although the numerical definitions (2–11 medications) and prevalence of polypharmacy (4%–97%) vary among studies, polypharmacy is consistently associated with adverse events. For example, adverse drug events are associated with anticholinergic drugs, pneumonia,18) and dysphagia.19,20) A list of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) for older people has been established.21-24) Therefore, polypharmacy and PIMs for older adults are problematic from a health risk perspective.11)

Although the relationship between medication status, symptomatology, and outcomes has been evaluated, data are limited regarding the prevalence of polypharmacy and PIMs and the association of polypharmacy and PIMs with swallowing function during the follow-up period among hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years with dysphagia. Regarding the association with polypharmacy and clinical outcomes, Matsumoto et al.25) reported that polypharmacy on admission was negatively associated with dysphagia and nutritional status on discharge among 257 consecutive stroke patients with sarcopenia in a rehabilitation hospital. Second, Maki et al.26) also reported a significant higher Barthel Index among inpatients in the Japan Medical Data Center claims database aged ≥65 years with acute hip fracture who received ≤5 medications compared with those who received ≥6 medications. Kose et al.19) reported a negative association between anticholinergics (PIMs) and patient functional state. However, data on the proportion of polypharmacy and PIMs in hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years with dysphagia are limited. In addition, information on the association between polypharmacy and PIMs at admission and swallowing function at discharge is scarce. Identifying these associations could help reduce the risk of prolonged hospitalization, overmedication, and increased healthcare costs.4,5)

Therefore, this study aimed to (1) describe the proportion of polypharmacy and PIMs in hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years with dysphagia and (2) evaluate the association of polypharmacy and PIMs with swallowing function at discharge. We hypothesized that the proportion of polypharmacy and PIMs on admission would be high and negatively associated with swallowing function at discharge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a 19‐site cohort study to describe the prevalence of polypharmacy and PIMs in hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years with dysphagia and to evaluate the association of polypharmacy and PIMs with swallowing function at discharge (Supplementary Fig. S1). The results are reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.27) This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trial Registry (No. UMIN000038281; Registration date: October 12, 2019). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yokohama City University Medical Center (No. B190700074; approval date: August 7, 2019). All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment or were given the right to refuse participation on an opt-out form. This study complied with the ethical guidelines for authorship and publication of Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research.28)

Data Source

The database was derived from a multicenter cohort study that used the Japanese Sarcopenic Dysphagia Database, which primarily aimed to assess the risk and contributing factors associated with sarcopenic dysphagia,16,29) using the REDCap web-base data-capturing system.30) In the database, we registered dysphagic patients aged ≥20 years and with a Food Intake LEVEL Scale (FILS) score of ≤831) from nine acute‐care hospitals, eight rehabilitation hospitals, two long‐term care hospitals, and one home‐visit rehabilitation team between November 2019 and March 2021 through a standardized questionnaire for data collection.

Study Participants

We included non‐consecutive inpatients aged ≥65 years with dysphagia, defined as a FILS score of ≤831) in the database. The exclusion criteria were patients aged 20–64 years and outpatients.

Outcome

The primary outcome was the FILS score at discharge. The FILS31) is used to evaluate swallowing function based on the patients’ level of food intake and the following 10‐point observer‐rated scale (discrete variable, ranging from 0 to 10): scores of 1–3 indicate various degrees of non‐oral food intake; scores of 4–6 indicate various degrees of oral food intake and alternative nutrition; scores of 7–8 indicate various degrees of oral food intake alone; a score of 9 indicates no dietary restriction, but with given medical consideration; and a score of 10 indicates normal oral food intake.

Exposure

We defined polypharmacy as the prescription of ≥5 medications.12,25) PIMs were identified based on the American Geriatrics Society 2023 Updated Beers Criteria.21) We collected medication information from electronic medical chart reviews on participant enrollment. Newly prescribed medication information taken within the 4 weeks before admission was excluded as a washout window. Two researchers (S.T. and M.N.) independently searched for and reviewed the medication codes to identify PIMs (Supplementary Table S1) and discussed with H.W. when necessary. The concordance rate between the researchers was 94.0% (141 of 150 individual medication names). We excluded aspirin and anticoagulant agents such as warfarin and rivaroxaban from our PIM assessment because of insufficient clinical information in our database to assess their appropriateness.

Covariates

We collected the following patient data: age (continuous variable); sex (binary variable); primary disease diagnosed (injuries, cerebral vascular diseases, respiratory diseases, cancer and other diseases); Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)32) (continuous variable); FILS at baseline (discrete variable); and general sarcopenia (binary variable), considered a proxy indication of systemic vulnerability, as diagnosed using the 2019 criteria of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia.33) We plotted a directed acyclic graph that was associated with polypharmacy and swallowing function based on previous studies6,7,10,14,25,34-36) (Supplementary Fig. S2) and discussions with our research team (registered nurses, physical therapists, registered dieticians, pharmacists, and medical doctors).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted according to polypharmacy exposure. First, we described patient characteristics using standard descriptive statistics of medians and IQRs for continuous variables and numbers (%) for categorical variables. Additionally, we described the medication categories of PIMs based on the 2023 Updated Beers Criteria prescribed at baseline. Second, we used descriptive statistics to summarize and repeated measures two-way ANOVA (time×polypharmacy) for the FILS score at discharge by overall and hospital type as effect modifiers owing to differences in patient characteristics and purpose for hospitalization between the three hospital types.

Third, we conducted a complete case analysis as a base-case analysis, considering that the proportion of missing values was <5%; thus, the effect of selection bias due to missing values was likely to be small37,38) (Supplementary Fig. S3). Because the FILS score is a finite discrete variable, we applied a generalized linear model with a Poisson distribution and log‐link function using Huber-type robust estimators (robustbase package in R)39) to evaluate the association of polypharmacy and PIMs with FILS score at discharge. In Model 1, we introduced the FILS score at discharge (discrete variable, ranging from 0 to 10) as the dependent variable and polypharmacy, age, sex, CCI, FILS score at baseline, and hospital type as independent variables in the analytical model. In Model 2, we added general sarcopenia as an independent variable to Model 1 to assume that it was an intermediate factor. In Model 3, we added primary diagnosis at hospitalization as an independent variable to Model 2. Additionally, we applied individual PIM categories with proportions >4% as exposure using Models 1–3.

We then conducted a sensitivity analysis. First, we applied a change cut-off value from 5 to 6, which was used as a secondary frequency in a previous systematic review,12) to assess differences in the results due to changing the cut-off value for polypharmacy. Second, we applied the multiple imputation approach under the missing-at-random assumption to check the results due to changes with multiple imputation. We generated 50 imputed datasets using the multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) procedure and pooled the results (mice package in R) using the standard Rubin’s rule.40,41) Third, we analyzed the associations using four primary diagnoses (injury, cerebrovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, and cancer) to check for groups with different effect sizes. Finally, for scenario analysis, we excluded participants diagnosed with conditions commonly associated with dysphagia, including esophageal cancer (10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems [ICD-10] codes: C15x), laryngeal cancer (C32x), pharyngeal cancer (C14x), stroke (I630, I631–I636, I638, I639, I600–I611, I613–I616, I619, I629, and G459), Alzheimer’s disease (G20), head injury (S00x–S19x), Parkinson disease (G20x), and pneumonia (J15x, J18x, and J690) to evaluate the results in participants without common conditions known to cause dysphagia.1,42)

We performed data processing and all statistical analyses using R version 4.0.5 for Mac (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)43) (Supplementary File).

RESULTS

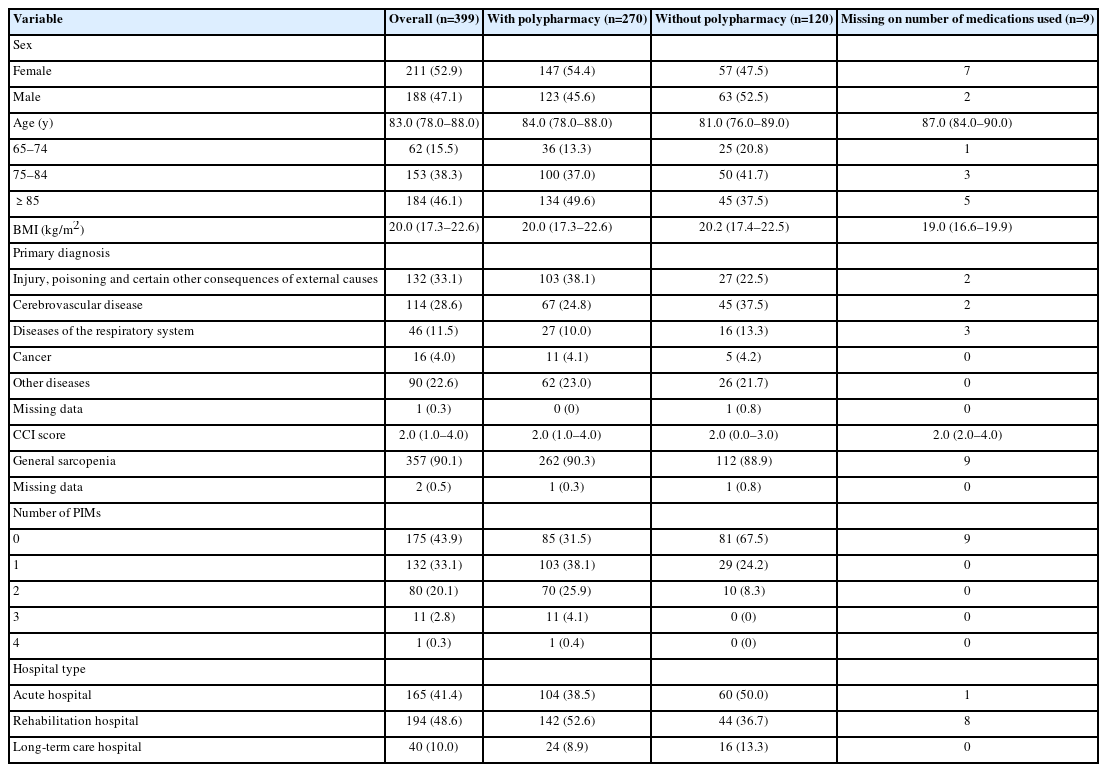

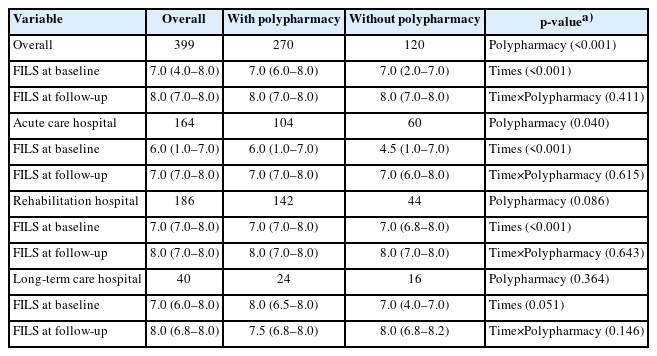

The final analysis included data from 399 patients (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. Patients with polypharmacy were more likely to be female, older, have PIMs, have injuries, and have been admitted to rehabilitation hospitals. They were also less likely to have cerebrovascular diseases and be admitted to acute-care hospitals. Of the nine patients with missing medication data, seven were female, five were aged ≥85 years, and nine had sarcopenia. The median follow‐up period was 51.0 days (IQR, 22.0–84.0 days).

Study flow. A total of 467 patients were registered in our database. Of these, 42 patients (9.0%) were excluded for the following reasons: 40 patients (8.6%) aged 20–64 years and two outpatients (0.4%). Of the 425 patients (91.0%), 26 patients occurred dead by follow‐up period and zero patients had been lost to follow‐up. Therefore, 399 patients (85.4%) were analyzed in the study.

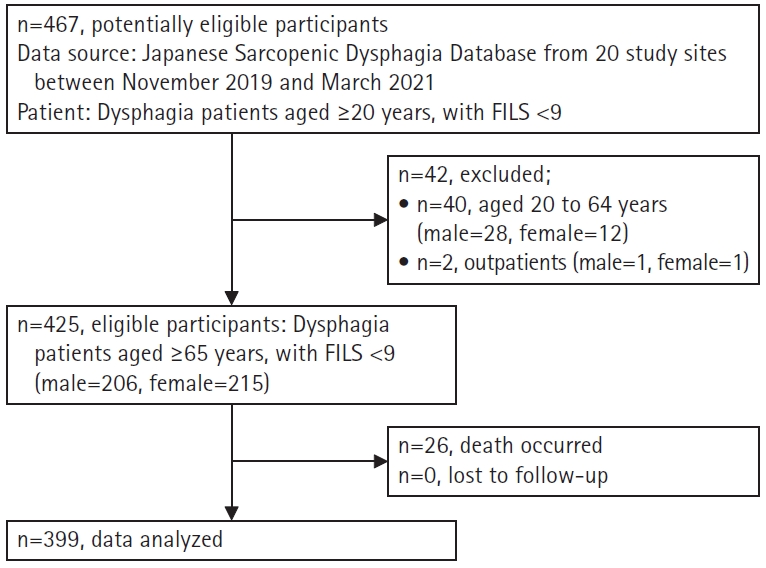

Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S4 provide information on polypharmacy and PIMs, respectively. A median of 6.0 medications was prescribed (IQR, 4.0–8.0). Polypharmacy, defined as the use of ≥5 medications and ≥6 medications, was observed in 270 (67.7%) and 231 (57.9%) participants, respectively. Additionally, 224 (56.1%) participants used a median of 1.0 PIMs (IQR, 0.0–1.0). Table 2 presents the medication categories of PIMs at admission. The most frequently prescribed PIMs were proton pump inhibitors (PPIs; 45.6%), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; 14.9%), antipsychotics (6.4%), and non-benzodiazepines (5.1%).

Description of medication categories of PIMs based on the Beers Criteria 2023 prescribed at baseline

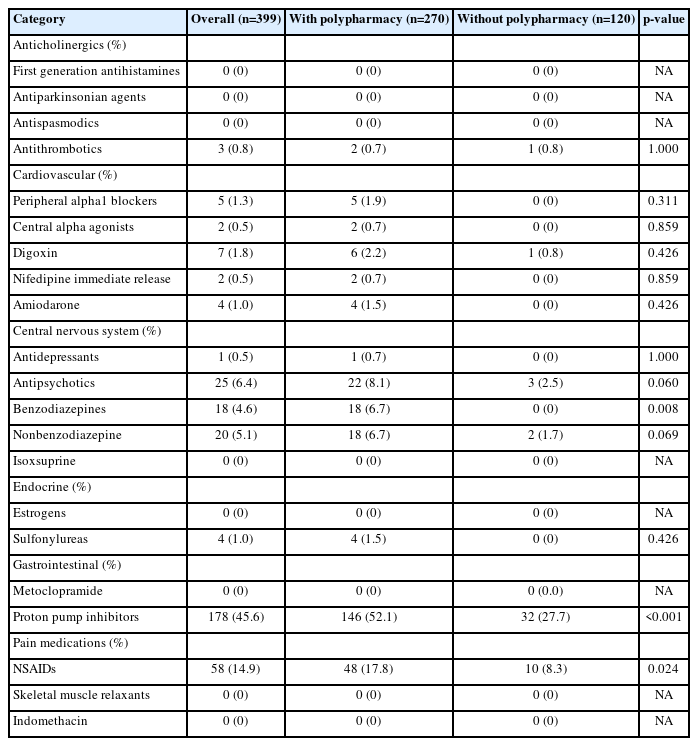

Table 3 summarizes the repeated-measures two-way ANOVA (time×polypharmacy) results for the FILS score at discharge among patients with and without polypharmacy across all hospitals (Supplementary Fig. S5) and by hospital type. While each factor (time and/or polypharmacy) showed a significant change in FILS score, the interaction term (time×polypharmacy) did not significantly change for either the overall participants (time×polypharmacy, p=0.41) or hospital type.

Table 4 presents the results of the association between polypharmacy and PIMs on admission and the FILS score at discharge. After adjusting for covariates, neither polypharmacy nor PIMs individual category was significantly associated with FILS score at discharge (β=0.05; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.04–0.13; p=0.30) in base‐case and sensitive analysis. Regarding the PIMs individual category, NSAID use was not associated with FILS score at discharge (β=0.09; 95% CI, -0.02–0.19; p=0.10). These results demonstrate trends similar to those observed in the sensitivity analysis, where the change cutoff value of polypharmacy and the MICE approach (Table 4).

In the sub-group analysis, participants with cancer (β=0.39; 95% CI, -0.21–0.99) showed a higher point estimate compared with overall (β=0.05; 95% CI, -0.04–0.13) and the other sub-group (β=0.07; 95% CI, -0.10–0.25 in injury; β=0.05; 95% CI, -0.11–0.20 in cerebrovascular diseases; β=0.05; 95% CI, -0.22–0.32 in respiratory diseases) in Model 2 in complete case analysis although no statistically significant differences were observed (Supplementary Table S2, S3). Among cancer patients without polypharmacy (n=5), two had laryngeal cancer, one had lung cancer, one had stomach cancer, and one had pancreatic cancer.

In the scenario analysis, the results, after excluding participants diagnosed with conditions commonly associated with dysphagia, were generally similar to those of the base case analysis (Supplementary Tables S4, S5).

DISCUSSION

This multicenter cohort study is the first to reveal the proportions of polypharmacy and PIM categories on admission among hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years with dysphagia and to evaluate the association of polypharmacy and PIM categories with swallowing function at discharge. In summary, we observed high proportions of polypharmacy and PIMs but no significant association between these prescribing conditions and swallowing function at discharge. These findings suggest that regular medication reviews8,44,45) for older adults with polypharmacy could help prevent frailty and maintain good body function, activities, participation, and QOL.6,7)

First, the proportions of polypharmacy and PIMs were 68% and 56%, respectively, among hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years with dysphagia. The high proportion of polypharmacy was similar to that in a recent systematic review,44) which reported a pooled proportion of 71% (95% CI, 57–86) among patients aged ≥60 years with frailty as a hospitalized subgroup from 14 studies. The proportion of PIMs in our study is higher than those reported in previous reviews,34,45) which reported proportions of 9% and 57% among older patients with frailty45) and cancer,34) respectively. From a clinical viewpoint, patients with multimorbidity are more likely to have polypharmacy and prescription of PIMs. The risks of polypharmacy and PIMs are likely to increase with comorbidities and complications13,21) and could be harmful to older people.11,21) Polypharmacy and PIMs are associated with increased risks of malnutrition, sarcopenia, falls, frailty, dysphagia, and cognitive impairment in older adults.6,7,10,11,13) Moreover, prescribed medications are often not changed despite improved clinical conditions.46) As a result, the risk of drug-drug interactions and prescription cascades increases. Therefore, healthcare providers should focus on routinely sorting polypharmacy because PIMs are likely to cause dysphagia as a side effect of drugs.

Second, contrary to our hypothesis, polypharmacy was not associated with swallowing function at discharge among hospitalized patients aged ≥65 years with dysphagia in the base case and sensitivity analyses. Our study showed different results to those of a previous single-center cohort study25) that reported a negative association between polypharmacy and swallowing function using the Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS) at discharge among stroke inpatients with sarcopenia in a convalescent rehabilitation ward. However, another study36) reported no association between polypharmacy and swallowing function in patients with stroke. Our findings showed a significant impact of time on FILS improvement, with a smaller trend in polypharmacy. According to previous studies,25,35,36,47) polypharmacy may inhibit the recovery of swallowing function by causing sarcopenia, malnutrition, and impaired activities of daily living. Moreover, these associations were modified using rehabilitation therapy and nutritional support.

Third, each category of PIMs was unrelated to swallowing function at discharge. This result differs from that of a previous study19) that reported a negative association between increased anticholinergic drug use during hospitalization and swallowing function at discharge among older inpatients with stroke in a convalescent rehabilitation ward. In the present study, none of the patients were prescribed anticholinergic drugs as PIMs on admission, and all had dysphagia. In contrast, in the previous study, the frequency of anticholinergic drug use on admission was 30%, and half of the patients had dysphagia (median FOIS score of 6; IQR, 5–7).19) One potential cause of these discrepancies is differences in the participants’ backgrounds. In addition, our results showed that PPIs, NSAIDs, and antipsychotics were the most frequently prescribed PIMs. The risks of long-term intake have been reported.21,48) However, we did not examine the association between the change in prescribing PIMs during hospitalization and the improvement of dysphagia because we did not collect medication information at follow-up.16) Further research is needed to examine the association between changes in the prescription of PIMs during hospitalization and the improvement of dysphagia.

An intriguing finding was that the cancer type could influence the association between polypharmacy and swallowing function at discharge. Contrary to our hypothesis, our results showed that polypharmacy was likely to be positively associated with FILS score at discharge in patients with cancer, although the number of patients was limited (Supplementary Tables S2, S3). Additionally, the proportion of cancer types differed between participants with and without polypharmacy. Given the small sample size, further research on the association between polypharmacy and dysphagia in patients with cancer is needed.

This study had some limitations. First, the measurement error in medication information could have resulted in an underestimation of the frequency of PIMs and their association with the outcome because of zero values (3.9%), missing numbers of medications (2.1%), and missing medication information (7.3%), despite using a standardized questionnaire. Second, the nature of this observational study design could not determine causality because of unmeasured confounding factors. However, this might have had a limited impact on the results because we considered the major confounding factors in previous studies6,7,10,14,25,34,49,50) (Supplementary Fig. S2) and multidisciplinary team discussions.

In conclusion, the results of this study revealed a high prevalence of polypharmacy and PIMs among hospitalized older adult patients with dysphagia. Although we did not identify an adverse association between polypharmacy and PIMs and subsequent swallowing function during the follow-up period, our findings suggest that regularly reviewing medications for the appropriateness of their prescriptions might help prevent frailty and maintain high body function, activities, participation, and QOL. In this study, the most frequently prescribed medications were PPIs and NSAIDs. Based on the indications for these drugs, the prophylactic use of PPIs to prevent NSAID-induced complications suggests that regular pain monitoring should inform the concurrent discontinuation of both PPIs and NSAIDs once they are no longer required. Additionally, even for PPIs prescribed alone, there is a defined duration of appropriate use, beyond which the risks of long-term intake have been reported. Therefore, the need for ongoing PPI therapies must be reviewed and reassessed to mitigate their potential adverse effects.

Notes

We thank all the collaborators from the Japanese Working Group on Sarcopenic Dysphagia for their clinical work, data collection, and data registration.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The researchers claim no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the JSPS‐KAKENHI, Grant Number 19H03979, during the conduct of the study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, ST, HO, HW, SN, RM; Analysis and interpretation of data, ST, HO, TN, HW; Writing–original draft preparation, ST, HO, TN; Writing–review and editing, ST, HO, TN, HW, MN, AS, SN, RM; Funding acquisition, HW.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.23.0203.

Study diagram. CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; FILS, Food Intake LEVEL Scale.

Covariate selection using a directed acyclic diagram.

Plot on missing information regarding data analysis.

Histogram for the number of medications used and PIMs at baseline: (A) number of medications used, (B) number of medications used by hospital type, (C) number of PIMs based on 2023 Updated Beers criteria, and (D) number of PIMs based on 2023 Updated Beers criteria by hospital type. PIM, potentially inappropriate medication; IQR, interquartile range.

Plot outcome data. Error bar indicates standard error. FILS, Food Intake LEVEL Scale.

List of medication codes with two researchers’ review

Description of outcome by each primary diseases

Association of polypharmacy and PIMs with dysphagia at discharge by each primary diseases

Description of outcome according to hospital type as scenario analysis

Association of polypharmacy and PIMs with dysphagia at discharge as scenario analysis

Studywarecode.R