A Multiple Case Study of Older Adults’ Internal Resiliency and Quality of Life during the COVID-19 Health Emergency

Article information

Abstract

Background

Few studies have been conducted on unique conditions such as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as an emerging health emergency, despite the strong link between resilience and quality of life in older persons. This study validated the expanded need-threat internal resiliency theory, which claims that an older person who establishes a strong sense of internal resiliency adapts to the situation by maintaining a better disposition.

Methods

The underlying methodology in this study was a qualitative design using multiple case studies with non-probability purposive sampling to choose the target participants aged 60 years and above.

Results

This cross-case analysis showed two major themes that explained and described the similarities and differences between the internal resiliency and quality of life of older adult participants with their respective sub-themes. Furthermore, this study concluded that older adults who have developed a strong sense of internal resilience, as manifested in the participants’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic, have sustained quality of life and better life satisfaction.

Conclusion

The study proposes a shift in the perspective of aging by emphasizing the importance of resilience as a dynamic process helping in the coping process and adapting to new emerging pandemics, leading to improved quality of life amid adversity.

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, initially discovered in 2019 in Wuhan, China, caused a global public health emergency, impacting hundreds of countries and severely affecting the general population health,1,2) particularly older people, worldwide.3,4) The likelihood of critical disease resulting from infection with the virus is particularly concerning for those >60 years of age. Hence, experts and older adult advocates have emphasized the importance of protecting, caring for, and supporting this vulnerable population.5) Different places throughout the country have been placed under a lockdown or community quarantine in response to the mounting threat of the pandemic, including travel restrictions, the closure of various public and private establishments and offices, and the stringent implementation of home isolation and social distancing preventive measures.6,7)

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, various researchers have investigated the impact of this pandemic on the psychological health of older people, which substantially influenced their life satisfaction and quality of life as individuals.4,5) As preventative measures, social distancing and isolation have negatively impacted the overall well-being and health of the older population.7) Most literature on the COVID-19 pandemic has identified the negative psychological impacts of such measures on older people because of their considerable implications on people’s daily life activities, affecting their holistic functioning and well-being.1,2,5)

During the COVID-19 global health emergency, people aged ≥60 years are at a higher risk of depression, poor health-related quality of life, and low life satisfaction.1,5) Restricted social networks and high levels of social isolation act as mediators, amplifying negative moods and reducing life satisfaction.8) Quality of life refers to one’s perception of the influence of illness or medical conditions, such as the COVID-19 crisis, on several domains of functioning, including physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects.1,4,9) Therefore, quality of life is a vital predictor of overall health and resilience.9) However, infectious disease outbreaks, such as emerging health emergencies, have negatively impacted these domains of functioning, particularly in older people, generating emotional distress and developing depressive symptoms, highly reducing the quality of life of this demographic group.1,5) Previous studies during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak highlighted the extensive decline in survivors’ quality of life, and its negative psychological implications, mainly because of the quarantine measures during the SARS outbreak.9)

Resilience has multiple facets that vary by age. For older people, common health problems may disproportionately affect resilience, whereas health crises such as COVID-19 exacerbate existing mental and physical conditions.2) Similarly, some people suffer from the mental effects of such situations, while others, such as the older population, are resilient and move on with their lives, as already documented.10) Internal resiliency refers to an older person’s ability to cope with adversity or a stressful experience (e.g., the COVID-19 crisis) and return to normalcy by surviving difficulties and positively adapting to circumstances.4,11,12) Adaptability improves life satisfaction and quality of life in older adults during emerging health emergencies.10,11)

Resilience refers to the capacity to improve after failure, making a mistake, or experiencing a poor outcome. A resilient individual would not allow difficulties or problems to impede their objectives or overall achievements. To successfully navigate challenging situations, Dr. Howard13,14) worked with hundreds of high achievers before developing the resilience pyramid, which includes Levels 1 to 5, which refer to energy, connection, thinking, awareness, and flow. Resilience is a multifaceted term and can be considered an attribute shared by all people to varying degrees, as well as a dynamic process with bidirectional relationships to developmental and environmental factors and a response or outcome to stress and adversity.15)

The original theory on need-threat internal resiliency asserts that older people's health needs can become health threats during the COVID-19 crisis and that older people must develop internal resiliency to maintain their integrity, well-being, and quality of life.4,12) However, the theory developed in response to this pandemic may not apply to other emerging health emergencies, necessitating the development of a more comprehensive theory to explain the coexistence of needs and threats in older adults as driving forces in the development of internal resiliency. The unique characteristics of this newly expanded theory provide more specific and detailed processes and outcomes that older people experience during such situations, which is central to the lives of such age groups allowing them to efficiently and effectively cope and adapt.11)

One assumption of connection is that “an older person who established a strong sense of internal resiliency adapts to the situation by maintaining a better disposition.”11) The link between resilience and quality of life in older people is long known, and resilience is strongly and favorably associated with subjective assessments of the quality of life in this age group.16) However, few studies have investigated this link in challenging situations, such as COVID-19.11) Most studies showed that negative situations experienced by individuals during global health emergencies reduced life satisfaction; circumstances, such as positive life experiences, social support, good social relations, and psychological strength increased life satisfaction.7,8,16) Through a multi-case design, the present study explored the similarities and differences between older adults’ internal resilience and quality of life while facing a health emergency to validate the theory’s propositions. When recommendations are deeply rooted in empirical data, multiple case studies offer a more compelling approach. Thus, varying situations enable a deeper exploration of research issues and the development of theories. Theoretical replication in many case studies tests the theory by contrasting the results with fresh cases. Theoretical replication can be demonstrated by additional waves of cases with opposing propositions if a series of examples show pattern matching between the data and propositions.17)

Study Objective

This study aimed to validate the proposition of the expanded need-threat internal resiliency theory on emerging health emergencies, which states that older persons who establish a strong sense of internal resiliency adapt to the situation to maintain a better disposition. Hence, this study explored the similarities and differences between older adults’ internal resiliency and quality of life while facing the COVID-19 health emergency. This study included open-ended questions during interviews to achieve this; these questions enquired the participants about (1) how they perceived the COVID-19 pandemic as a person, (2) the challenges they encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic and how they coped with such situations, (3) how their coping and or adapting strategies differed from those of other older adults during this COVID-19 pandemic, (4) their living conditions during this COVID-19 pandemic, (5) their life satisfaction during this COVID-19 pandemic, (6) their quality of life during this COVID-19 pandemic, and (7) some life lessons they learned from this COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

We performed a qualitative multiple-case study to provide more detailed descriptions and explanations of the phenomena. The case study method is useful for comprehending a topic in-depth in the context of a real-world event, phenomenon, or concern. In multiple case studies, several cases are carefully selected to allow for comparisons across multiple cases and/or replications.18) Many disciplines, particularly the social sciences, frequently use this well-known research technique. While there are numerous definitions of a case study, they all call for a detailed analysis of an event or phenomenon in its original context. For this reason, a "naturalistic" design is often used instead of an "experimental" design, which attempts to exert control over and manipulate the variable(s) of interest.18,19)

Participants and Locale

This study involved older persons aged ≥60 years who had been staying in Marawi City since the official declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 until now. The inclusion criteria were: (1) at least 60 years of age at the start of the pandemic, (2) having evolved coping strategies in response to this emerging health emergency and displaying characteristics of adaptation to this health crisis through the identification of at least one or more specific types of coping activities used in facing the COVID-19 pandemic, and (3) willingness to participate in the study irrespective of their other socio-demographic profiles. Participants in the target sample were excluded if they had cognitive, memory, or physical disabilities that affected their experiences in this situation.

Sampling Technique

Non-probability purposive snowball sampling was used to select sample participants from six older adults based on data saturation. In qualitative research, purposeful sampling is widely used to identify and select cases with relevant information on the topic under study; this includes determining and selecting individuals or groups with specialist knowledge or experience in a phenomenon of interest. It also entails considering participants’ availability and willingness to participate, including their ability to convey their experiences and thoughts in a direct, expressive, and thoughtful manner.20) Snowball sampling is a technique in which study participants or others with access to potential participants recommend individuals having experience or characteristics comparable to the researcher’s interests (Naderifar et al.21)). Up to 3–4 cases for comparison can be efficiently handled in a multiple-case study using purposeful sampling comparison.18)

Instrument and Data Collection

We conducted semi-structured interviews. The method included a guide questionnaire that allowed the order to be modified depending on the conversation, allowing the researcher to emphasize certain questions while including new ones.22) For instance, questions about the participant’s physical, social, psychological, and spiritual well-being (e.g., how do praying and reading the holy book help you cope with the COVID-19 pandemic and maintain your good outlook?) as older adults during health emergencies were added to explicitly explore their quality of life from a holistic perspective. The schedule was set based on the convenience and approval of the volunteer participants. The interviews were completed within 30–60 minutes, based on the participant’s area of comfort and convenience. The guided questionnaire contained eight general questions translated into the participant’s layman’s dialect to delve further into their experiences with the phenomenon under consideration; probing questions were added based on their flexible responses to these guide questions. Before being used in the study, three qualitative research experts in the respective field of discipline thoroughly reviewed this set of questions. The most typical qualitative data source in healthcare research is semi-structured, in-depth interviews, generally utilized in qualitative investigations. This approach frequently involves discussions between the researcher and participant and uses a flexible interview methodology, including additional follow-up questions, probes, and remarks. This method enables researchers to collect unstructured data, delve into sensitive and often private subjects, and examine participants’ ideas, feelings, and viewpoints on a particular subject.23)

Ethical Considerations

The Research Ethics Board of Cebu Normal University approved this study before participant enrollment (No. REC-01-31-22). Additionally, the researchers requested permission from the Office of Senior Citizens of Marawi City, a unit of the Department of Social Welfare and Development. Basic ethical principles in conducting qualitative studies, such as beneficence, respect for human dignity, and justice, were observed throughout the study. Moreover, informed consent was obtained from the participants to ensure that they had received appropriate information about the study, comprehended the material, and had the right to refuse at any moment during the interview without reason.24)

Although they were free to avoid answering any questions that would make them uncomfortable and withdraw from the study at any moment, the participants were not subjected to any physical or psychological threat. They were also assured that a guidance counselor would be available before and after the interview if they experienced psychological or emotional stress. The researcher ensured that the study participants’ ethical rights were upheld and that no moral lapses occurred throughout the investigation. Pseudonyms or codes were used to safeguard the respondents’ privacy. The researcher also spoke with the participants about their preference to participate in the study at home, at another location alone, or with assistance. Furthermore, COVID-19 health safety procedures were strictly adhered to protect the researcher and the participants.

Also, this study complied the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing in the Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research.25)

Data Analysis

This study conducted a cross-case analysis. This analysis allows researchers to compare similarities and differences in the events, actions, and processes that comprise the units of analysis in this case study. Themes, similarities, and distinctions between cases are used to connect the evidence gained to the proposition using cross-case analysis.26) This research strategy simplifies the comparison of the parallels and discrepancies among the events, behaviors, and procedures that form the cornerstone of the case study analysis. With a cross-case analysis, the investigator’s expertise expands beyond a single case. It sparks the researcher’s creativity, brings up new problems, offers fresh viewpoints, produces alternative explanations, develops models, and conjures ideals and utopias.27,28) Additionally, this analysis makes it possible for researchers to identify the variables that could have affected the case’s outcomes; seek an explanation for why one case is unique or similar to others; make sense of puzzling or unusual findings; or better express concepts, hypotheses, or theories that found or developed from the initial case. Cross-case analysis helps researchers to understand the potential links between disparate examples, gather data from the first case, develop and refine ideas, and establish or test theories. By applying cross-case analysis, researchers can compare examples from one or more settings, communities, or groups.28) We applied the Miles–Huberman approach, which entails three continuous flows of operations. These include (1) data reduction, the process of choosing, concentrating, simplifying, abstracting, and altering the outcomes of investigations; (2) data display, in which organization and compression of the information allows the drawing of conclusions and the taking of action utilizing a “tool-box”; and (3) conclusion drawing and verification, where qualitative analysts begin to determine what things mean from the outset of data collection by noticing regularities, patterns, explanations, potential configurations, causal processes, and propositions.29)

Rigor and Trustworthiness

Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability, the four criteria created by Lincoln and Guba (1985) in ensuring rigor and trustworthiness, were strictly observed and used in the execution of this qualitative investigation.30) To prove its validity, the researchers reviewed each participant’s transcript to identify patterns among all participants to interpret an event so that those who have had it may relate to it easily. While describing the demographic and geographical parameters of the study to check for transferability, the researchers provided a thorough description of the groups under consideration. Peers were engaged in the analysis process for dependability and a thorough explanation of the research methodology was provided. Finally, confirmability was evaluated using a self-critical mindset that considered how the researcher’s preconceptions affected the findings.

RESULTS

This section discusses the results of this qualitative multiple case study that aimed to validate one of the propositions of expanded need-threat internal resiliency, that an “older person who established a strong sense of internal resiliency adapts to situation in maintaining a better disposition,” using cross-case analysis. This study included six senior citizens following set parameters, and data saturation was observed in the data analysis process during transcription. This was undertaken through unit analysis, which involved connecting the transcribed data to the proposition under consideration and interpreting the findings to support this proposition. Following the unit analysis, we developed subthemes and categorized them further into themes connected to the proposition. The results revealed two major themes and their respective subthemes. Theme 1 discusses the differences and similarities in older individuals' coping strategies and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, also known as “internal resiliency,” which the study participants used to cope effectively with the COVID-19 health emergency. These internal resiliency strategies include acceptance of COVID-19 as an illness, self-discipline and strict observance of health protocols, the practice of healthy lifestyle activities, trust in healthcare professionals, and a strong spirit and strengthening of spiritual beliefs.

Theme 2 describes the similarities and differences in older adults’ life disposition during the COVID-19 pandemic. The participants described their life disposition, particularly in terms of life satisfaction and quality of life, as stable and even improved despite the challenges and adversities they faced (and still face) as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, despite their vulnerability as a population group. Life disposition included a sustained source of living and basic needs, the absence of illness, family as a source of satisfaction, and a strengthened spiritual connection. We identified two notable life dispositions related to the expected consequences of COVID-19 crisis management, including restricted social life and psychological disturbances.

Participant 1 (P1) was a 64-year-old married woman residing with her extended family. Her primary means of support were family and government assistance, such as pensions for older citizens. Compared with before the pandemic, during the pandemic, she spent most of her time at home and frequently visited her relatives during the pandemic. She believed the COVID-19 pandemic to be similar to emerging illnesses in her early childhood, including fever, chills, and cough. Hence, following the authorities' instructions to stay home was the primary step in preventing this illness.

Participant 2 (P2) was a 62-year-old married man who lived with his wife and children. He was currently employed by the government in a provincial agency. He claimed that the COVID-19 pandemic had affected the entire world and that the best way to end this crisis was to adhere to health protocols, including getting vaccinated, wearing masks and face shields, and avoiding close contact with others. He also had symptoms of COVID-19 during the outbreak but had never undergone testing.

Participant 3 (P3) was a 70-year-old married man who resided with his family in their ancestral home. He was a retired elementary school teacher and administrator who received a monthly government pension. He held a doctorate in education and had dedicated his entire life to teaching until reaching retirement age. He confined himself to their home throughout the pandemic and kept busy in their backyard with gardening as a way of coping. He claimed to have carefully observed practicing a balanced diet, exercising, and taking maintenance medications on time to avoid contracting this disease.

Participant 4 (P4) was a 61-year-old married woman who had been working as staff in a university for more than 30 years. Before the COVID-19 crisis, she preferred to visit her siblings and other family members; however, the pandemic prevented her from doing so. She nevertheless consistently showed up for work. She had been exposed to a person with COVID-19 but never tested positive for the illness. She acknowledged that the pandemic brought many difficulties and obstacles to her personal life, but she managed to overcome them.

Participant 5 (P1) was a 64-year-old married man who lived with his wife and children. Before retiring at 60 years of age, he was an overseas Filipino worker (OFW) in the Middle East. After retiring overseas, his business became his primary source of income. He claimed that his business suffered significantly due to the societal restrictions and lockdowns brought on by the pandemic, yet he was still able to operate normally, even during the peak of the crisis. He enjoyed interacting with friends and family, especially before the pandemic, but still managed to maintain the same attitude during the pandemic.

Participant 6 (P6) was a 67-year-old woman who was a retired elementary-level teacher. As she was already widowed, her primary source of income, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, was her government-issued monthly pension. She claimed that the lockdowns and social limitations imposed on the community at the height of the crisis made this pandemic one of the most difficult periods of her life. She had liked to roam around malls after receiving her monthly pension but could not do so after the pandemic began; however, she enjoyed staying at home with her family, especially her grandchildren.

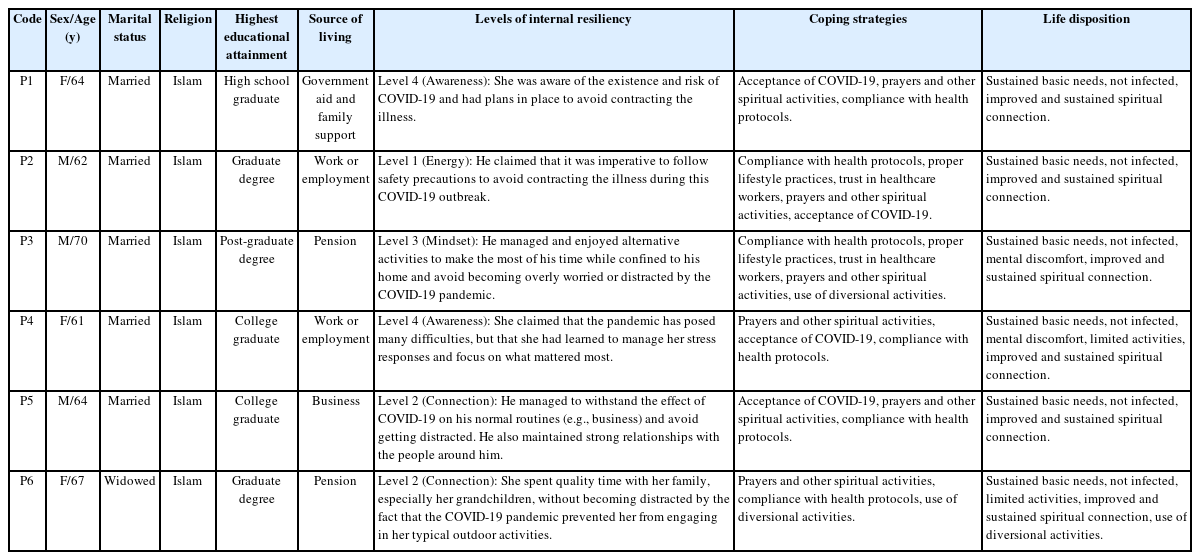

Table 1 shows the cross-case matrix of the participants’ profiles in terms of age, sex, marital status, religion, highest educational attainment, source of living, level of resiliency, coping strategies, and life disposition. This study involved three male and three female Muslim older adults aged between 61 and 70 years, most of whom were married. Majority had earned graduate degrees or at least college degrees. Four relied on jobs, employment, and pensions to make ends meet. Their levels of resiliency were based on Howard’s resilience pyramid, which has five levels: level 1 (energy), level 2 (awareness), level 3 (mindset), level 4 (connection), and level 5 (flow).

Cross-case matrix of the participants’ profiles and levels of internal resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic

In level 1 (energy), a person must improve their physical vigor. Controlling energy requires examining routines and ways of life to determine what is or is not working. This pyramid level supports the other levels and serves as the basis for resilience. The pyramid's base level, or level 2, is awareness and aids in stabilizing the foundation. The important markers of this level are growing self-awareness and understanding of the causes of stress and how to deal with them. At this level, concentration on what is vital is achieved by controlling stress triggers. Level 3 (mindset) calls for intentionally using thoughts to focus on answers and avoid ruminating on difficulties once control over energy and awareness of the manifestation of our stress is achieved. Level 2 strategies were beneficial. In this step, individuals should also make goals and have a vision for each day or their lives.

In level 4 (connection), a person can help others to become more powerful. Individuals at this level should already be able to manage their emotions and energy levels, as well as set boundaries and be aware of their limitations. Individuals should also encourage others to be their best versions while simultaneously emphasizing the value of their limits to prevent demotivation and burnout.

Finally, in level 5 (flow), individuals safeguard their value as human beings and treat themselves as high-performing. By incorporating these steps, obstacles can be overcome, and progress can continue. Through this process, individuals discover more about themselves, develop new abilities, and overcome the overwhelming feelings that formerly held them back.13,14)

Thematic Results

Two major themes were derived with their respective subthemes to explain and describe the differences and similarities in coping strategies and life dispositions of the older adult participants amid the COVID-19 crisis. These coping strategies and measures, known as “internal resiliency,” were assumed to be the underlying factors that helped these individuals to effectively adapt to such health emergencies, leading to the maintenance of stability and better life disposition in late life, consistent with the proposition of the expanded need-threat internal resiliency theory, which states that “older person who established a strong sense of internal resiliency adapts to situation in maintaining a better disposition.” These themes and subthemes are summarized in Table 2 and discussed further in the following sections.

Theme 1: Coping strategies and measures used by older adults to adapt well to the COVID-19 pandemic

This theme describes the differences and similarities in coping strategies used by older adults to adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic. These “internal resiliency” strategies were created by such people to adapt well to dangers, trauma, or significant sources of stress, collectively known as emerging health emergencies, to achieve and maintain a sense of purpose and vigor, and to emerge stronger amid such trying circumstances, resulting in sustenance or improved outlook in later life. The internal resiliency strategies used by the participants included acceptance of COVID-19 as an illness, self-discipline and strict observance of health protocols, the practice of healthy lifestyle activities, trust in healthcare professionals, and a strong spirit and strengthening of spiritual beliefs.

Sub-theme 1 (Acceptance of COVID-19 as an illness): The first sub-theme refers to the acceptance of the existence of COVID-19 as an illness, which is among the emotion-focused coping strategies practiced by older adults in facing emerging health emergencies. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“Sakun na kagya adun a wata akun a miklas sa medicine na ditawn die makapangi-ngisa na paniwala ako a adun talaga a covid-19 sie sa ingud tano aya. Pkaylay tano sa social media ago mga news a tanto a madakul a kya apektowan ago so pud na mindod sa limo o ALLAH swt misabap sa gyangkae a paniyakit.” [Since I have a son who has studied medicine and was able to ask questions, I believe in the existence of COVID-19 in my community in my situation. We see on social media and the news that many have been affected, and others have even died of this illness]. – P2

“So mga restrictions na tanto a margun lalo so kapakindodolona ko pud a taw, ogaid na paka adap-ako ka kagya inaccept akun angkae a masoswa-swa ago dapat na pka follow tano so mga bitikan ago policy.” [The restrictions are very difficult, especially in terms of socializing with other people, but I cope with this by accepting the situation and the need to follow rules and regulations.] – P5

Sub-theme 2 (Self-discipline and strict observance of health protocols): The second subtheme considers the participants' self-discipline and strict adherence to health protocols during the COVID-19 crisis to successfully avoid contracting the illness and adjust to the situation. This problem-focused coping mechanism can be employed when facing difficulties. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“So sitwasyon tano imanto na siebo anan matitimo ko taw. Dapat na may disiplina tayo at alam ntin ang mga protocols na binibigay ng otoridad ago dapat na ino-observe natin yon. Sabinga nila na aya mapiya a taw na so katawan iyan so kapanang-gila. Na kagya sabap sa aya ta ipkaluk ta na obata mapositive ago ma quarantine odi na mawit sa ospital na aya pingola-olako na so makapantag ko paano maiwasan at ma spread a gyangkae a paniyakit ago igira adun a magugudam akun na diyako die quarantine sa kwarto a sakun bo.” [Our situation today depends on people. We must have discipline, and we should know the protocols given by the authorities and observe them. They stated that a good person knows how to avoid such issues. Because we are afraid that we might be positive, quarantined, or hospitalized, what I did was to prevent and spread this illness, so I usually quarantine myself in the room alone when I feel something is new.] – P2

“Aya syowa akun na pagosar ako sa preventive measures datar o kasulot sa mask, kausar sa alcohol, ago face shield, ago social distancing igira sisie sa public a mga areas.” [What I did was I used preventive measures like wearing masks, limiting alcohol use, using face shields, and social distancing in public areas.] – P3

Sub-theme 3 (Practice of healthy lifestyle activities): The third subtheme focused on the participants' adoption of healthy lifestyle practices to strengthen their immunity to COVID-19, allowing them to respond effectively to the community's ongoing emergent health emergency. These lifestyle practices included eating a balanced diet, exercising, ensuring strict compliance with medication maintenance, taking vitamin supplements, and engaging in various diversionary activities for mental health. These measures are dimensions of both problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“Gyangkae a covid-19 na myakapanang-gila so taw. So di pag-exercise na myakapag exercise. Apya so dingka kun na myakan ka lagido gulay ago prutas ka pantagbo sa an pakabagur so lawas ka para kaiwasan ka gyoto a covid-19 a paniyakit.” [People must be careful about COVID-19. Those who don’t exercise are able to exercise. Even if you don’t eat vegetables and fruits, you are now eating them to strengthen your body and avoid getting infected with this illness.] – P2

“Dyakopn die mag exercise ago regular so kapaginom akun sa maintenance akun a bolong para sa highblood ago vitamins. Diyakopn die garden sa walay para pkatumbang apya maito.” [I exercise and regularly take my maintenance medication for high blood pressure, and I take vitamins. I also do some gardening at home so that I remain entertained somehow.] – P3

Sub-theme 4 (Trust in healthcare professionals): The fourth subtheme refers to the trust given by the participants to healthcare professionals facing the COVID-19 pandemic. These people have served as sources of information and guidance, especially for observing health protocols against such illnesses and managing symptoms related to COVID-19. This practice is part of problem-focused coping, particularly using informational support to adapt and emerge well in such emerging health emergencies. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“Sie raknun na kagya adun a mga wata akun a miklas sa medicine na pagisaan akun siran ago sie ako kiran puk-wa sa advice.” [For my part, since I have a son studying medicine, I usually ask him for advice.] – P2

“Sakun na paratiyayaan akun so mga pkanug akun ko mga doctor ago nurses a health measure sa gya covid-19. Di ako basta basta psong ko madakul a taw ago bako pliyo a daa sabap a ipliyo akun.” [As for me, I believe what I hear from doctors and nurses about health measures for covid-19. I don’t just go out to meet many people and come out for no good reason.] – P3

Sub-theme 5 (Strong spirit and strengthening of spiritual beliefs): The fifth subtheme refers to the strong spiritual relationships developed by the participants as an overarching coping strategy in facing and adapting to the COVID-19 crisis. These activities involved the practice of the five daily prayers as Muslims, reading the holy book (Qur’an), putting their trust in the creator, doing a lot of dhikr, or constantly remembering the name of God (ALLAH swt). This type of coping is emotion-focused coping, which is unique and widely used among the older population during times of adversity. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“Naka-adjust ako dahil nilakasan ko ang loob ko at basta malaka e paratiyaya ko ALLAH (swt) na pkakayangka apya antonaa klase a problema. Pakadakulun ka so simbangka ago so tasbik ka, ago kapangadi sa qur’an, na In shaa ALLAH na ipkalimo o ALLAH swt so manosiya a lagidoto. So kasambayang na aya mala pakawgop rakun nago aya lalayon akun a pipikirin na so ALLAH swt.” [I was able to adjust because I took courage, and as long as you have great faith in ALLAH (SWT), you can withstand any problem. We must increase our prayers and always read the Qur’an (a holy book for Muslims); surely, he will always help and bless us. Our prayers can help us a lot, and I always remember God’s (ALLAH swt) name.] – P1

“Sa prayer ko dinadaan ang lahat. Ang ALLAH swt lang ang nakaka control sa mga bagay bagay.” [In my prayer, everything goes through. Only ALLAH swt can control things.] – P4

Theme 2: Life dispositions of older adults in the COVID-19 pandemic

This theme describes the similarities and differences in the life dispositions of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. The participants sustained or even achieved better life satisfaction and quality of life despite the challenges and adversities they faced as persons in this health crisis, in addition to their vulnerabilities as a population group. This life disposition, as described by the participants, includes a sustained source of living and basic needs, the absence of illness, family as the source of satisfaction, and a strengthened spiritual connection. However, we identified two notable life dispositions related to the expected consequences of the management of the COVID-19 crisis, including restricted social life and psychological disturbance.

Sub-theme 1 (Sustained source of living and basic needs): The first subtheme describes how older adults in this study have sustained their sources of living and basic needs while facing the COVID-19 crisis despite the challenges that this pandemic has posed to the financial and economic stability of the community. Most participants stated that their primary source of living had consistently sustained their basic needs amid the pandemic, paving the way for them to live good and even improved lives as older adults. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“Mabuti, ganun parin ang aking pamumuhay. In shaa ALLAH na walang pagbabago kasi nakaka-kain parin ako ng maayos at walang problema sa pera dahil hindi naman ako maluhong tao.” [Good, my living conditions are the same. In Shaa ALLAH, there are no changes because I can still eat well and have no money issues since I am not a luxury person.] – P1

“Okay nman ang pamumuhay ko kahit covid-19 pandemic kasi government employee tayo at may sweldo parin kahit papano. Mas nakatipid pa tayo kasi hindi tayo makalabas at pasyal sa mga malls.” [My life is good even during the COVID-19 pandemic because I am a government employee and still earn a salary. We can save even more because we can neither go outside nor visit malls.] – P4

Sub-theme 2 (Absence of illness): The second subtheme describes how, despite their vulnerability as a population group, older persons in this study managed to avoid getting sick during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, they accepted the fact that certain physiological changes exist due to their age, which is a normal part of aging and is not directly related to the illness caused by COVID-19 virus. The absence of illness during health emergencies has helped older adults sustain their life satisfaction and quality of life amid adversities. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“So kambobolawasan akun na mapyadn ogaid na basta pakatowa so edad na dirundn kada so mga sakit sa lawas ka part anan o ageing.” [My physical health is so far good; however, when we get old, it is normal to feel some changes that include body aches as part of aging.] – P1

“Normal so kaledad a kapka-oyag-oyag akun. Mapiyadn odi na health a magugudam akun kasi na dako katakdi angkaya a COVID-19.” [My quality of life is normal. I feel physically healthy because I am not affected by Covid-19.] – P5

“Wala namang masyadong problema sa physical na aspeto sa awa ng ALLAH swt. Wala naman akung mga nararamdaman na sakit simula magka pandemya hanggang ngayon.” [There is not much problem with my physical health at the mercy of ALLAH swt. I have not felt any pain since the pandemic began.] – P6

Sub-theme 3 (Family as a source of satisfaction): The third subtheme describes how older adults sustained their quality of life despite the COVID-19 crisis with the help of their families, who served as sources of satisfaction. This source of satisfaction made their lives easier and more resilient in dealing with such a health emergency in the community, despite the challenges and struggles of the movement restrictions and lockdowns, especially for vulnerable groups such as the older population. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“Alhamdulillah ka mapipiyatadn ago satisfied ako ka pka ilay akun so pamilyakun ago mapiya so environment akun.” [Alhamdullilah, I am still good and satisfied as long as I can see my family and have a good environment.] – P3

“Pkaconsider akun a mapiyadn odi na average so kapka-oyag-oyag akun imanto kagya diyako makapliyo-liyo a daa bakun pipikira ogaid na madakul so oras para ko family bonding.” [I consider my living conditions as good or average as of now because I cannot go outside without worrying, although there is always time for family bonding.] – P5

Sub-theme 4 (Strengthened spiritual connection): The fourth subtheme describes how the older adults in this study have sustained their living conditions despite the adversities brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic through a strengthened spiritual connection with ALLAH (swt), which led to a sustained and even enhanced quality of life in old age. Their prayers and faith in God helped, guided, and aided them in facing this health emergency. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“Mas myakabagur so paratiyaya akun ko ALLAH swt na sie ako mambo pukwa sa bagur para magagakn angkaya a t’pung a inibgay nyan ruktano.” [My faith in ALLAH swt grew stronger than before, and that is where I draw courage to pass this test that he gave us.] – P1

“So sambayang akun ago paratiyaya ko ALLAH swt na aya mala a myakawgop rakun para magagakun langon aya ago mawyag-oyag lagid o kapka-oyag-oyag akun kayko dapun a COVID.” [My prayers and faith in ALLAH swt helped me overcome everything and live the same way as before when there was no pandemic.] – P4

Sub-theme 5 (Restricted social life and finding alternative ways to connect): The fifth subtheme describes how the older adults in this study experienced changes in their normal routines of socialization due to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly when lockdowns and movement restrictions were put in place in the community to mitigate the rapid spread of illness among the general population, including older adults. However, such restrictions have resulted in a lack of community socialization but have not totally hindered their communicating means with friends and relatives. The participants used alternatives such as social media and other digital platforms to consistently connect with other people. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“Sie ko kapakindudulona ko pud a taw na myakayto kagya babawalan kmi ran mliyo-liyo ago kokontrol’n eran so kandadalakaw kagya so edad ame mambo malbod katakdan a gya paniyakit. Ogaid na so kapakimbityarae ko mga tunganay ago layok akun na sige sige parin ago knaba pman myaputol ka adun a facebook akun ago pakatawag ako kiran parin sag yaya a cellphone akun.” [Socialization is minimal only because it is forbidden to go outside because movements are restricted and limited because of our age vulnerabilities. However, my communication with my relatives and friends is still consistent and was not totally cut off because I have Facebook and can still call them via mobile phone.] – P4

“Diyakodn makipundodolona odi na makipumbityarae s apud a taw ago di ako dn pagattend sa mga kalilimod lagido ka-kawing ka dikun kapakay lalo sie rkami a mga myaka edad.” [I no longer socialize with other people and can no longer attend gatherings like weddings because it is prohibited, especially for older adults.] – P6

Sub-theme 6 (Psychological disturbance): The sixth subtheme describes how the COVID-19 crisis caused psychological disturbances in older adults. Most admitted that its uncertainty as an illness resulted in some fear and worrying while facing the adversities of such a health emergency. Although it has created some disturbances in their mental health as a person, the crisis has not completely negatively affected their life dispositions because of their strong faith and belief in God (ALLAH swt) as the controller of all things in this world and hereafter. According to them, the pandemic was destined to happen and will eventually disappear in God’s perfect time. This subtheme was supported by the following participant statements:

“Sie ko kapamimikiran na mapipiyakodn ogaid na datar oba sa didalum na maaluk akobo ka obako badn masakit sag yaya covid-19. Pero so ALLAH swt na malae limo ka asar ka panarig kawn ago pakabagarun ka so paratiyaya kawn na In shaa ALLAH na dikadn maribat ka pagogopan ka niyan ago ikalimo kaniyan.” [I am still good in terms of psychological health; however, underneath this, I have little fear of getting infected with this illness. However, ALLAH swt is merciful as long as we trust him and continually strengthen our faith in him, then he will help us, especially in times like this.] – P3

“Mapipiyadn so kapamimikiran akun ogaid na igira kwan na pkapikir akun a ibarat oba-ako katakdi odi na so isako pamilyakun sangkae a covid na di siran pakabaw ago dadun a kataam eran, inoto diyakun plipatan obako di makasusulot sa mask ago pamangni ako sa tabang ko ALLAH swt.” [I still have a good mind, but sometimes this thought haunts my mind what if I or one of my family members get infected with it and are unable to smell or taste anything, so I always wear a mask and ask for help from ALLAH swt.] – P4

DISCUSSION

This study was primarily conducted to validate one of the propositions of expanded need-threat internal resiliency theory, which states that in times of emerging health emergency (e.g., the COVID-19 crisis), “an older person who established a strong sense of internal resiliency adapts to the situation in maintaining a better disposition.” This multiple-case study identified two major themes addressing this proposition, describing the similarities and differences between coping strategies known as “internal resiliency” developed by older adults to adapt and cope well with such stressful and challenging situations, resulting in sustained or improved life dispositions.

These themes included Theme 1 “Coping strategies and measures of older adults used in adapting well to the COVID-19 pandemic.” This theme included five subthemes (acceptance of COVID-19 as an illness, self-discipline and strict observance of health protocols, the practice of healthy lifestyle activities, trust in healthcare professionals, and strong spirit and strengthening of spiritual beliefs); and Theme 2 “Life disposition of older adults in the COVID-19 pandemic.” This theme included six subthemes (sustained source of living and basic needs, absence of illness, family as the source of satisfaction, strengthened spiritual connection, restricted social life, and psychological disturbance).

Older people are frequently considered a high-risk population owing to high incidence and fatality rates in most emergent health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 crisis. This is one of the most recent trends.31) People must make significant adjustments to their daily routines to cope with challenging life events such as the COVID-19 pandemic.32) Other containment measures implemented in residential care communities and residences are exceptionally harmful to older individuals, such as limiting outdoor activities and visiting schedules.31,32) These measures go beyond general social distancing policies. However, some factors, including a person's coping strategies and resilience, may influence whether potentially stressful situations arising because of the pandemic lead to better or poorer health and well-being.31)

Resilience and coping skills are cognitive and behavioral capabilities that might assist older persons in adjusting to changes in their way of life caused by adversities, such as health crises.11,33) Studies on older adults in Asia, particularly in The Philippines and South Korea, have reported positive correlations between resilience, coping mechanisms, life satisfaction, and quality of life. Therefore, coping mechanisms and resilience play critical roles in protecting and promoting a better way of life, particularly among older adults.33)

Quality of life is one dimension impacted by contextual circumstances experienced during this life period, such as emerging health emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.4) These contextual elements can negatively affect the central components of life. Individuals’ coping mechanisms for dealing with environmental stressors mediate the connection between the two.31,34)

The results of this study highlighted that older adult participants made use of both problem-focused (e.g., self-discipline and strict observance of health protocols, the practice of healthy lifestyle activities, and trust in healthcare professionals) and emotion-focused (e.g., acceptance of COVID-19 as an illness, the practice of healthy lifestyle activities, and strong spirit and strengthening of spiritual beliefs) coping strategies and measures in facing the COVID-19 health crisis to adapt to such situations, as reflected in Theme 1.

Hence, this strong sense of coping, known as “internal resiliency,” established by the participants, allowed them to effectively sustain and even improve their life disposition throughout this health emergency, as reflected in the different sub-themes describing their life disposition as older adults. These sub-themes included a sustained source of living and basic needs, absence of illness, family as the source of satisfaction, and strengthened spiritual connection, as reflected in Theme 2.

These results are consistent with those reported by the study in the United States, in which 74% of the 5,180 older adult respondents described using a variety of coping mechanisms to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic, including problem and emotion-focused coping, which frequently involved exercising and staying outdoors, changing routines, following public health measures, maintaining social connections, and changing attitudes. Such coping primarily led to improved lifestyle choices, quality of life, and self-perception of aging well.35) Furthermore, acceptance (risk ratio=2.710; 95% confidence interval, 3.926–1.493) as a coping strategy negatively predicted the COVID-19-related stress score in a study of older adults coping strategies and their significant connection with COVID-19 pandemic-related stress. This further implies that acceptance as a coping approach positively correlates with the capacity to handle stressful conditions such as the COVID-19 health crisis.36)

Although fear, anxiety, and loneliness were continuing stressors in a different study of older couples living alone in India during the COVID-19 pandemic, many of these individuals adapted and emerged resilient to the changing situation because of the various coping strategies used to deal with the health crisis, including accepting one's destiny, developing one's own health literacy, engaging in spiritual practices, and returning to creative leisure activities.37)

In a review on on the efficiency of coping mechanisms in older persons, Choudhury and Shivani38) reported that coping mechanisms are imperative for enhancing well-being, particularly mental health, during a pandemic. Problem- and emotion-focused coping are some of the most frequently used techniques,4,31,38) consistent with the observations among the participants in the present qualitative multiple-case study. Hence, the results of this study successfully prove that utilizing coping techniques to deal with a health crisis promotes and enhances the health and life disposition of older adults, as claimed by the expanded need-threat internal resiliency theory.

Conclusion

The theory of expanded need-threat internal resilience in emerging health emergencies defines the internal resilience of older adults as their capacity to perceive and recognize the threat of an emerging health emergency, allowing them to develop specific coping skills, such as physical, psychological, social, and spiritual strategies, to successfully and efficiently recover from adversities; thrive with persistent purpose; evolve in turbulent, challenging, and uncertain situations, resulting in sustained or improved quality of life while facing a global health crisis. The results of the present study provide strong evidence supporting the claim of the proposition of the expanded need-threat internal resiliency theory that during an emerging health emergency, “an older person who established a strong sense of internal resiliency adapts to the situation in maintaining a better disposition.” This further provides a foundational structure for existing knowledge about the relationship between internal resilience as a vital factor for older adults to sustain and even improve life disposition during a health crisis. Therefore, caregivers of older adults, healthcare workers, community leaders, and those who support the older population should always consider promoting holistic coping strategies, as it empowers and supports such individuals in times of emerging health emergencies.

Limitations

To date, few studies have reported on this phenomenon, especially in this locality. Hence, this study offers baseline literature in this age range, especially considering their vulnerability to emerging health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, this study substantially strengthens the literature body supporting the broader idea of need-threat internal resiliency in older persons. However, this study included only five adults aged ≥60 years in a single area. Thus, older adults in various regions may be able to describe their quality of life and develop internal resilience. Additionally, the participants' educational backgrounds did not accurately reflect each grade or level, even though the value of a multiple case study is increased by including the experiences of participants with low levels of education. Therefore, future studies should use different research approaches and incorporate the demographics of older adults to establish how internal resilience and quality of life coexist when confronted with developing medical issues.

Recommendation

This study offers a change in the perspective of aging by highlighting the significance of resilience as a dynamic process aiding in the coping process and adapting to newly emerging pandemics, leading to successful aging, longevity, and quality of life. It also emphasizes the importance of creating policies and preventive and intervention programs that support older people’s resilience and the accompanying factors that may attenuate the negative effects of adversity on their physical and psychological health. When considering older adults from the perspective of their identified internal resilience, it is evident that dealing with spirituality is fundamental; therefore, this factor must be acknowledged to provide adequate support to older people. Thus, programs and support groups related to spirituality must be strengthened and highlighted in their communities as an essential approach to providing a holistic and people-centered response to older people amid these adversities.

The community is recommended to work on developing religious activities during these trying times with the aid of technology, such as online seminars and small-group discussions with religious leaders, as spirituality is a vital coping strategy for older people that helps them to cultivate strong internal resilience, which can be achieved through collaboration between local leaders, the general public, and line government agencies (e.g., the Department of Health and the Department of Social Welfare & Department). In addition, it is becoming increasingly clear that health professionals and care providers must be equipped with the knowledge and ability to recognize and assist patients' spiritual needs to provide holistic care for this population group.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The researchers claim no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, JMS; Data Curation, JMS; Investigation, JMS, DRP, DJEA, NTD, JTPA; Methodology, JMS, DRP; Project administration, JMS, DJEA, NTD, JTPA; Supervision, JMS, DRP; Writing-original draft, JMS; Writing-review & editing, JMS, DRP, DJEA, NTD, JTPA.