Policies and Transformation of Long-Term Care System in Taiwan

Article information

Abstract

The Taiwanese government has been facing severe challenges pressed by population ageing. The government started taking the issue of long-term care seriously since the first rotation of the political parties in 2000. However, early plans for long-term care were limited in terms of coverage. The Long-Term Care 2.0 Plan—a tax-funded, universal plan—was implemented in 2016. Soon after its implementation, the number of service organizations and the coverage of service increased sharply. This paper takes Taiwan as an example to discuss the designs of long-term care, and strategies to expand services. With many countries currently under pressure in long term care needs, Taiwan's experience could serve as a good example on how to achieve such policy goal within a short period of time. In addition, policy challenges for expanding long-term care are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Background in Taiwan

Taiwan, like many other countries, is under pressure to develop effective policies in response to population aging. Trends of declining fertility rates and expanding lifespan together have contributed to the growth of the “gray population”. The proportion of the population aged 65 years and over has doubled from 7% in 1993 to 14% in 2018. In addition, life expectancy has increased over the last 50 years to 77.5 and 84.0 years for men and women, respectively.1) Although nearly 55.5% of Taiwan’s older people live with their adult children,2) the increasing proportion of women in the labor market and the declining ratio of those needing care to potential caregivers have raised questions regarding families’ ability to care for the disabled older population.3)

Official projections show that the number of people in need of long-term care will increase from 577,457 in 2017 to 771,431 in 2026.4) To respond to the rapidly growing need for care in these population, Taiwan is seeking a clear direction in which to adjust the development of long-term care.

Small-scale long-term care plans run by local governments first emerged in the 1990s. The central government initiated a major nationwide plan for long-term care in 2007, began planning for universal long-term care insurance in 2009, and finalized the policy plan in 2015. However, the 2016 presidential election resulted in a shift in political power, and the newly elected government abandoned the proposal for a universal long-term care system and instead launched a tax-funded universal long-term care system. The new plan has been successful in terms of expanding service coverage. The number of people receiving long-term care services increased from 9,148 in 2008 to 258,351 in 2019, accounting for 41.47% of those in need.5)

This document uses Taiwan as an example to discuss strategies for developing long-term care. Taiwan has successfully expanded its long-term care coverage within a short-time period and its experiences may serve as a good example for other countries facing rapid population aging and under pressure to expand such services.

This document comprises three parts. The first briefly reviews the development of long-term care policies since the 1990s and introduces several policy reforms for long-term care services. The second part introduces strategies for expanding long-term care, especially focusing on Long-Term Care 2.0 (LTC 2.0). The final part, the discussion, includes policy suggestions, implications for providers, and influences on users and families.

EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF TAIWAN’S LONG-TERM CARE POLICY

While population aging has been an important policy issue since the early 1990s, the focus of political debates on aging policy was primarily income maintenance. Long-term care was ignored. There are two reasons for this. First, under Taiwan’s divided pension system, only those who worked in special occupational groups could receive adequate pensions after retirement. Most of the population faced the risk of old-age poverty. Therefore, the government was under pressure to enhance the income support system for older people. Second, it was reasonable for the government to prioritize cash benefits over care services under the pressures of rapid population aging and political competition, as this could increase the number of beneficiaries in a short time. Once the government had secured financial resources, the social administration system could deliver cash benefits to eligible individuals without delay. In contrast, it would have been more challenging to quickly expand the care services system as that would have required not only financial resources but also extra manpower and service providers. The latter cannot easily be quickly implemented. In the 1990s in Taiwan, the issue of establishing a comprehensive old age income maintenance system was at the core of policy debates in all major political elections.4)

However, the issue of developing a comprehensive long-term care system received less attention in the political arena before the 2010s. The government had implemented several programs regarding care for older people between the 1990s and early 2000s. The Kuomintang (KMT) government put two programs into practice in 1998, namely, the Improving Care Services for Older People Program and the Three-Year Plan on Long-term Care for Older People. This was the first time that the Taiwanese government addressed long-term care as a policy issue and developed related programs. However, these programs were limited. The government lacked funds for these schemes. Related ministries were required to implement services with existing financial resources. These schemes were considered insignificant, and no academic studies or governmental reports have evaluated their performance. However, they demonstrated that the government had noticed the importance of developing a care system for older people.

In 2000, the Democratic Progress Party (DPP) replaced the KMT as a the ruling party. It was the first time in Taiwanese history. The DPP government implemented two phases of the 3-year Care Service and Care Industry Development Plan, from 2002 to 2007, that focused on the development of community and home care services. Although those programs were extended to cover those not categorized as low income in 2002, these schemes benefited only a small portion of the population. For instance, when the first stage of the Plan was completed in 2004, only 12,000 people received domiciliary services.5)

In 2007, a 10-Year Long-Term Care Project, LTC 1.0, was implemented. The LTC 1.0 plan required that local governments set up care management systems and develop in-kind services such as various home care and community care services. They were also expected to provide subsidies for these services.6)

The 10-year plan is important as it orientated the directions and strategies for Taiwan’s long-term care development. However, LTC 1.0 faced three main challenges. First, from the administrative aspect, funding for the plan remained insufficient. According to central government regulations, local governments, had to share fixed copayment ratios for services and thus they, especially poorer local governments, lacked funds to support services. Second, from the service provision aspect, institutional care was not included and only non-profit organizations (NPOs) could provide services. Moreover, NPOs had to wait a long time for benefits, usually over half a year. In addition, people were unfamiliar with the application procedure and regulations. Even when they decided to apply for services, the process usually took over a month, and support for families was insufficient.

Because funding was inadequate, in addition to issues with service supply and application procedures, the KMT sought to build a single-payer universal social insurance system to solve those problems. The newly elected president, Ma Ying-jeou, pledged, during his campaign, to introduce long-term care insurance, and the Task Force for Long-term Care Insurance Planning was formed in July 2009. The name of the task force demonstrated the government’s policy direction to establish long-term care insurance. It soon finalized its planning and published the Report on Long-term Care Insurance Planning in December 2009 as a policy guideline that proposed adopting compulsory social insurance to fund long-term care services.7)

The KMT’s introduction of the concept of long-term care insurance was driven mainly by two forces. The first was its political competition with the DPP. Its political appeal was that a social insurance-style long-term care system is better than a tax-funded one in terms of financial sustainability. The second was the pressure for Taiwan to catch up with its neighboring countries as Japan and South Korea implementing long-term care insurance in 2000 and 2008, respectively. Many Taiwanese politicians saw that as a progressive system to follow. A government document stated that “our neighbor countries Japan and Korea implemented long-term care insurance when the proportions of people aged 65 or over exceeded 15.7% and 9.9%, respectively. Therefore, based on their experience, we should soon establish long-term care insurance in response to trends of population aging”.8)

The KMT’s planning for long-term care continued after the report was published in 2009. The timetable set by the report put the proposed long-term care insurance into force by 2016. The Executive Yuan passed a long-term care insurance bill in July 2015. However, it did not take further action for immediate enactment and the KMT lost the presidential election in January 2016. Debate during the long-term care insurance design process focused on four issues. First, they looked to Germany for guidance on designing population coverage for the total population, meanwhile, Japan’s model including only those over 40 years of age. Second, in terms of benefits, the committee members had to decide whether both in-kind and in-cash services would be provided, as in Germany, or only in-kind services would be provided, as is the case in Japan. Moreover, regarding the administration system, it was unknown whether the insurance could solve issues such as worker shortages and whether the service supply was sufficient. Finally, if and when the single-payer social insurance institution was established, policymakers would have to determine the role and function of local governments.9,10) The KMT spent 8 years designing and working to overcome these challenges. During this period, the Long-Term Care Service Act was passed in June 2015, which provided a legislative base for constructing the LTC service system. In 2016, however, the KMT lost power, and the plan for long-term care insurance was abandoned.

The result of the 2016 presidential election again changed the history of Taiwan’s long-term care. The DPP took over governing and had a different approach toward long-term care services. The new president, Tsai Ing-Wen, had published a policy platform on long-term care during her campaign. The platform pledged to implement a New 10-year Plan for Long-Term Care, or the 2.0 Plan of 10-year Plan for Long-Term Care, now known as Long-Term Care 2.0 (LTC 2.0). The DPP government criticized the KMT’s plan for compulsory universal long-term care insurance. Instead, LTC 2.0 was to be financed by taxes. The DPP argued that it would be unfair and unjust to collect social insurance contributions for long-term care service, as the service system was not yet in place. The government instead would fund the long-term care system by increasing estate, gift, and tobacco taxes.

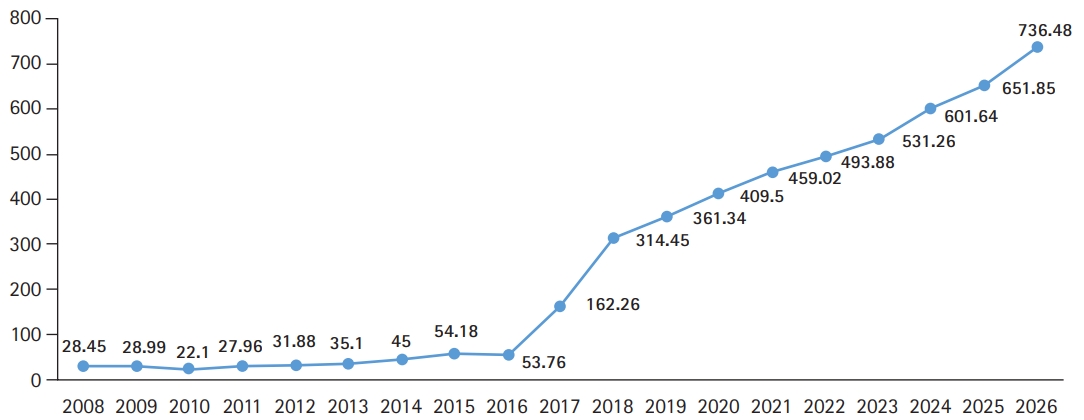

The important consideration is the shift in Taiwan’s politics. Between 2000 and 2016, Taiwan’s two major political parties traded leadership, which meant several sudden changes in how the central government envisioned long-term care policy. For example, the DPP implemented the 10-year Plan for Long-Term Care in 2007. When the KMT replaced the DPP in 2008, they planned universal long-term care insurance starting in 2009. Additionally, the most recent change, in 2016, which saw a complete handover in both presidential and legislative control, led to a major shift in long-term care policy, moving from a policy based on social insurance to one based on welfare. It is important to note that the long-term care system in Taiwan is still in the early stages of expansion. As Fig. 1 indicates, it was not until 2016 that the government significantly increased its investment of financial resources into long-term care.

LTC 2.0 AND EXPANSION OF SERVICES

In 2017, the DPP implemented the LTC 2.0, which included the following aims: first, to construct a high-quality, fair-priced, and universal LTC care system; second, to put aging-in-place values into practice and provide support for families via multiple and continuous home- and community-based institutional types of care; third, to extend care to include preventive care; and fourth, to integrate multipurpose supportive community services and link discharge preparation services to home-based medical care. Moreover, the eligible population included not only older people aged 65 years and over with functional limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) but was also expanded to include people with dementia aged 50 years and over and older people aged 65 years and over with frailty.11)

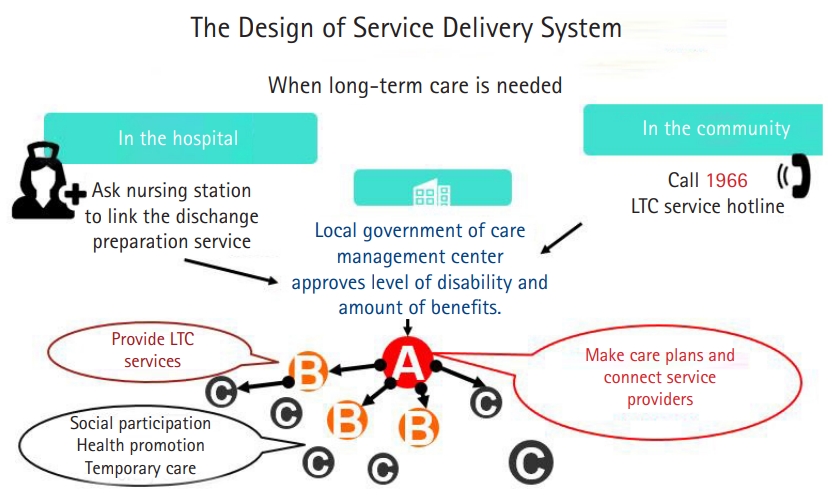

LTC 2.0 covers 17 types of services. The following items were added: dementia care, aboriginal community-integrated services, small-size multiple-function centers (linking adult daycare, respite care, and others), multiple support services for family caregiver centers, a community-based integration care system (ABC system), community health preventive care, preventive and delaying disability programs, links to discharge plans from hospitals, and links to home-based medical care. The delivery flow for accessing long-term care in the LTC 2.0 system begins with a long-term care management center, which is a department of local governments. Users can access long-term care management center services by themselves or may be transferred to the center from hospitals or clinics. Then care managers at the management centers assess care needs; formulate a care plan; collaborate with the ABC network to communicate and negotiate with users, families, and providers; and implement the care plan. Eligibility determination uses a long-term care case-mix system checklist categorized into 11 parts, including ADL, instrumental ADL (IADL), cognition level, behavioral changes, rehabilitation, home environment, and caregiver stress. Initially, recipients were classified into eight categories, with those in level 8 having the most severe disabilities.11,12)

The community-integrated care system, a three-layered service network termed the ABC network, is the core innovation in the LTC 2.0 reform. Users requiring long-term care, regardless of whether they stay in the hospital or live in the community, can connect with the local government’s care manager, whose role is to approve the disability level and benefit amounts. Then, service provider A’s function is to develop a care plan and connect the service providers. The missions of B and C, respectively, are to provide long-term care services and promote community care stations, as well as to help people find opportunities to participate in social activities and promote health and temporary care (Fig. 2).

The service delivery system design (source: the Ministry of Health and Welfare, https://1966.gov.tw/LTC/cp-3636-42415-201.html)

The payment system was also modified in 2018, during the LTC 2.0 reform. Previously, fees for home-based care were based on service hours. In the new system, payment is categorized into four parts: personal (home and day care services, etc.) and professional care (home nursing, rehabilitation, nutrition service, etc.; NT $334–$1,206/month), transportation (NT $56–$80/month), assistive devices and home modifications (NT $1,333/month), and respite care for family caregivers (NT $1,078–$1,617/month). According to the disability level, each case has an upper limit and each type of service delivery is paid by fee-for-service. Users and family choose what they prefer to use from a menu of professional and personal care services. Co-payments are waived for low-income users. Users are responsible for charges for service usage exceeding the upper limit.11)

The LTC 2.0 reform has seven successes. First, population coverage has increased. Compared to 29% in 2018, the growth rate of new applications in 2019 was almost 52%. This rapid expansion of service is a remarkable achievement of Taiwan’s long-term care system. The reduction of co-payments was the key factor because service users had to share 30% of fees as co-payments for long-term care before LTC 2.0 was implemented. The copayment rate was reduced to 16% under LTC 2.0. This reduction generated motivation for eligible users to take up the service.

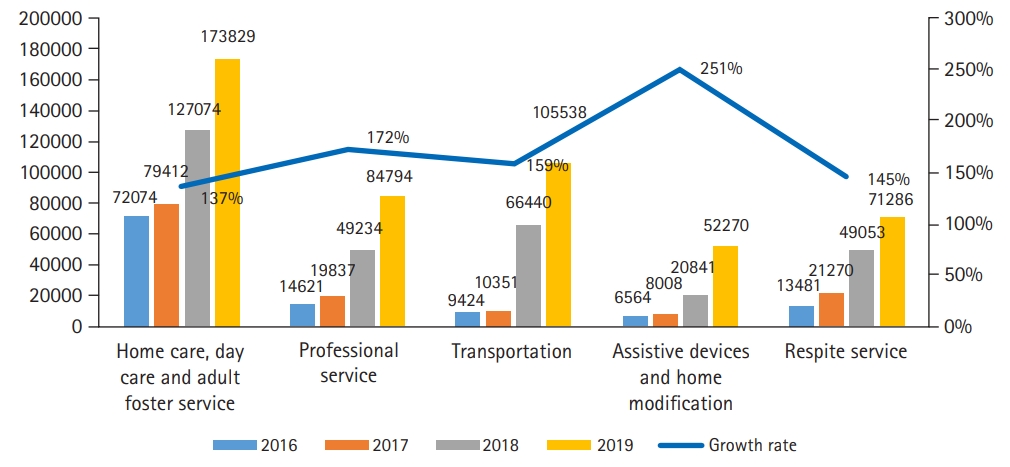

Second, the contract system for service providers has been radically changed. In the early stage of LTC 2.0, long-term care organizations were required to go through a complex and long process to compete for a limited number of positions as contracted service organizations. Moreover, only NPOs could join the service system. The Long-Term Care Service Act enacted in 2017 allows all long-term care organizations, both for- and non-profit, to join the system. This resulted in a boom in the number of service organizations immediately after its implementation, which has helped increase the availability of long-term care services. Fig. 3 shows the increased rates for each of the services. Compared to the previous outcome, the LTC 2.0 policy reform seeks to provide incentives to grow or expand the long-term care industry.

Third, the system of payment for service fees has been modified. The new and generous payment system not only encourages for-profit organizations to join but also attracts “local” manpower. For instance, home care services were previously paid according to the hours of service provided. This payment method put a limit on care workers’ salaries, as there was a maximum number of work hours for a job. The new fee-for-service system permits care workers now to increase their salaries by improving their service efficiency. The more service they provide, the higher the pay. This new payment method has resulted in substantial increases in care workers’ salaries. Therefore, more manpower has participated in the service system, which underpins the expansion of the LTC 2.0 service system.

Fourth, additional incentives are provided for long-term care organizations to expand to rural areas with insufficient service. These include more subsidies from the government and higher payment for services. For instance, governmental financial subsidies allow long-term care institutions to buy more vehicles to provide transportation services in rural areas. Additionally, service providers can receive up to 20% extra payment for each service they provide in rural areas.

Fifth, LTC 2.0 not only focuses on the needs of care recipients but also considers the care burdens of family caregivers. Every city already has family caregiver support centers and each local service center is supposed to provide all of the following 8 types of services: case management, individual and group home care skills training, respite service, psychological counseling, support groups, relaxation and stress-management courses or activities, and telephone support.

Sixth, the number of dementia service centers has increased. These centers help clients receive rapid diagnoses and access necessary resources. Seventh, the reform is allowing employers of migrant care workers to apply for respite and professional care services. Fig. 4 clearly shows the significance in terms of increases in service usage since 2018.

The final success is the expansion of community health preventive and delaying disability programs. The government cites Japan as a reference for its long-term care system. From late August to early September, 2016, a team comprising Taiwan’s Deputy Minister of the Department of Health and Welfare and several high-level officers visited Japan to learn about its community care system. The report submitted by the visiting group suggested that Japan’s “comprehensive community social care model” should be a model for Taiwan’s long-term care development.13) This visitation report and frequent communication visits between Taiwan’s and Japan’s NPOs have not only become the ideal for the ABC framework but have also led to the expansion of Taiwan’s long-term care system into preventive healthcare. Community care stations and health centers provide health training programs as well as hope for older people by helping users form exercise habits and perform health self-management to postpone or avoid disability.

Despite its many successes, LTC 2.0 still has room for improvement. From the administrative viewpoint, the long-term care service was managed by two separate departments before 2017. To address this problem, the central government established a new department, the Long-term Care Bureau. However, at the local government level, long-term care services are managed by two separate departments: the social department controls the majority of service supply, whereas care management centers belong to the health department. This results in unbalanced services development, an issue that is prevalent in different counties.

On the supply side, LTC 2.0 payment is only for community/home services. Thus, these generous payments have attracted both providers and manpower for the community and home care sectors. However, neither resources nor payment is provided for institutional care, which has resulted in a significant disadvantage for institutional care. Therefore, the number of care institutions has not grown with the rise in the aging population. Fortunately, in September of 2019, the central government announced that it would provide subsidies for users of institutional care. However, it will be some time before we see any effects in terms of institutional growth.

One characteristic of LTC 2.0 was an attempt to establish a community-integrated service network with the ABC network functioning as a team and community care station, or C, comprising the largest in number. According to the original design, each township set an A, with a role requiring both day and home care services. Each junior school district set a B, and every three villages set at least a C. The ideal numbers of ABCs are shown in Fig. 5. Notwithstanding, service providers prefer to take the A role, meaning they can take control of care packages. Some service providers have persuaded the government to waive the requirements of A. The new payment system allows no incentives for service providers to build community integration networks. This has resulted in continued insufficiently effective basic community care station numbers and functions; moreover, the cooperative relationships between service providers also require improvement. The original plan intended that the ABC network work like a pyramid, with C (community care stations) comprising the largest number and serving as a foundation for the network as a whole. But in reality, what we have seen is shaped more like a diamond, with the majority being B, service providers and A, coordinators, with community care stations, C, still lacking (Fig. 5).

The shape of the ABC network (A indicates coordinators; B, service providers; C, community care stations).

From the user and family viewpoints, the policy so fervently encourages people to use LTC 2.0 that the labor department has continually loosened regulations regarding hiring family migrant care workers. For example, people age 85 years or older with only one item of disability can now hire a live-in migrant care worker. Because family migrant care workers are cheaper and more flexible than formal services, the number of family migrant care workers continues to increase. The main care model in Taiwan includes four choices: institutional care (11%), family migrant care workers (26%), care responsibility provided only by family members (40%), or using LTC 2.0 services (23%).14)

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

It has been almost two decades since a World Health Organization-sponsored study15) encouraged governments to provide universal long-term care services rather than small-scale, selective services. One of its most important recommendations was to view long-term care as a “normal life” risk. The risk is that many families may become impoverished by paying for long-term care services. Therefore, governments should, at least partly, shoulder the responsibility for developing public long-term care services. Taiwan’s experience has shown that, with effective strategies, the government can rapidly expand long-term care.

However, Taiwan’s experience also demonstrates the substantial impacts of political factors on the development of long-term care. A universal long-term care insurance plan based on years of study was abandoned overnight because of a shift in political power. The DPP government has stated repeatedly that the current tax-funded system is sustainable. However, scholars remain suspicious of this claim. Campaigns for universal long-term care insurance have never faded. With coverage expanding rapidly, the government is facing growing pressure to secure adequate funding for long-term care. The next important policy task is to build a consensus regarding a sustainable financial plan.

At the administrative level, the Ministry of Health and Welfare has established the LTC Division to integrate resources in the health and social sectors. Further cooperation with the labor division is needed for manpower training and providing information to employers of migrant care workers regarding the use of long-term care services. In addition, as local governments are responsible for supervising long-term care services, the central government must provide them more resources and professional support to improve the quality of services.

In terms of service, institutional care remains a missing piece for long-term care in Taiwan. The Taiwanese government’s policy orientation for long-term care is to encourage aging in place. Under such a policy direction, most resources have been allocated to in-home care and community care. The government is reluctant to invest resources in institutional care. However, institutional care is an important part of long-term care and should be included in the long-term care system so that people in need can get better service.

The implication in Taiwan’s case is that establishing an accessible, affordable, universal long-term care service system with good-quality, upstream prevention to delay disability and provide support services for family caregivers is a step in the right direction. These strategies allow families more time and energy to care for their older family members and fulfill the policy goal of “aging in place”.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The researchers claim no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, CC, TF; Writing-original draft, CC; Writing-review & editing, TF.