|

|

- Search

| Ann Geriatr Med Res > Volume 24(3); 2020 > Article |

|

Abstract

The long-term care insurance (LTCI) system was introduced in Japan in 2000 to address the demands of older persons with disabilities based on the concept of a user-oriented social insurance system with support for independence. Older people with a certification for LTCI service needs can utilize facility services, in-home services, and community-based services depending on their physical and cognitive impairments. After the implementation of the LTCI system, there was a rapid increase in persons certified for LTCI service needs, with a corresponding increase in the financial burden on the government. Therefore, the Japanese government started a disability prevention program in which older people were screened for frailty by the Kihon checklist in addition to a high-risk approach with appropriate prevention programs in each community. After unsatisfactory outcomes of the high-risk approach for disability prevention, the government changed the primary strategy to a community-based population strategy to build a community to seamlessly provide preventive, medical, and long-term care and welfare and housing services to all individuals. Further improvement of the community-based integrated care system is needed for healthy aging in a superaged society.

Hidenin (悲田院 in Japanese) appears to be the first precursor of today’s welfare institutions for older people in Japan. Hidenin is a Buddhist temple built in the 6th century in Kyoto that aimed to care for the poor and children, as well as older people, who could not look after themselves and who could not be cared for by their community or family. It is one of the oldest welfare facilities for older people in the world. As in other Asian countries, Buddhism was an influential factor behind early welfare activities in Japan.

The proportion of older people aged 65 years or over in Japan was less than 5% in 1950. After the first and second baby booms following World War II, Japan has experienced unprecedented aging of its population. Owing to the low birth rate and an increasing trend in the number of nuclear families in addition to population aging, in the late 20th century, many older people were admitted to and remained in hospitals because their families were unable or unwilling to look after them. The associated increase in medical expenditure for this so-called “social admission” became a serious issue for society. Although the Japanese government implemented a 10-year strategy for the health and welfare of older people (the “Gold Plan”) in 1989, the system encountered financial issues owing to its reliance on tax revenue and its increasing expenditure. This is a major reason for the implementation of the long-term care insurance (LTCI) system.

Japan is the most aged country in the world. People aged 65 years or older accounted for 28.4% of the total population in 2019 and that proportion is expected to reach a plateau of approximately 40% in 2040–2050 (Fig. 1).1) In 2018, the average life expectancy was 81.25 years for men and 87.32 years for women. There are approximately 6 million people aged 85 years or older, and this number will reach 10 million in 2040 when the total population in Japan will be approximately 100 million (currently 120 million). In contrast, the population aged 40–64 years will start to decrease after 2021. Thus, we will live in a society where approximately 1 in 10 people will be 85 years or older. In addition, the numbers of older adults with disabilities and those living alone were 4.71 million in 2019 and 5.93 million, respectively, in 2015 and will increase dramatically, which is expected to result in a further financial burden on society.

As the country’s demographics change so does the disease structure. The demand for medical and welfare systems needs to be changed if the increasing number of older people require long-term care for longer periods along with the trend toward nuclear families and the aging of caregivers in families. The Japanese government launched the LTCI system in 2000 considering future demographics and national finances concerning population aging and related healthcare needs. The LTCI system in Japan was based on three basic concepts: support for independence, social insurance, and a user-oriented system. The aims of establishing the LTCI system were to shift the burden of family caregiving to social solidarity, shift cost-sharing with insurance premiums, and integrate long-term medical care and welfare services.

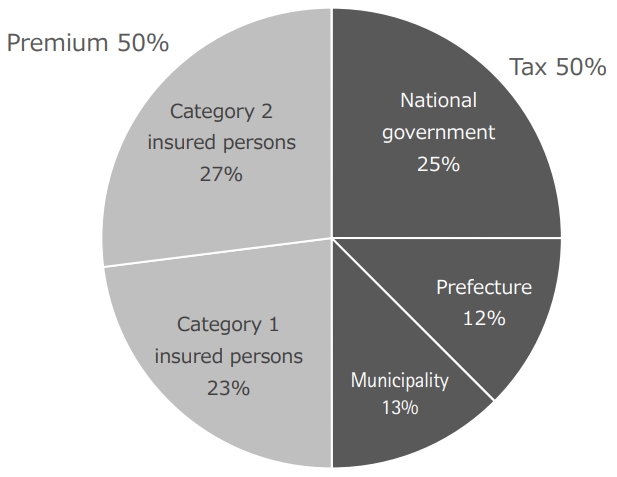

The LTCI budget in Japan consists of premiums (50%) and taxes (50%).2) In this system, every citizen aged 40 years or over pays premiums, whereas the taxes are derived from the national government (25%), prefecture (12.5%), and municipality (12.5%) (Fig. 2). In Japan’s LTCI system, older adults who are certified for the LTCI service pay a 10% copayment for services; the remaining 90% is covered by the LTCI budget.

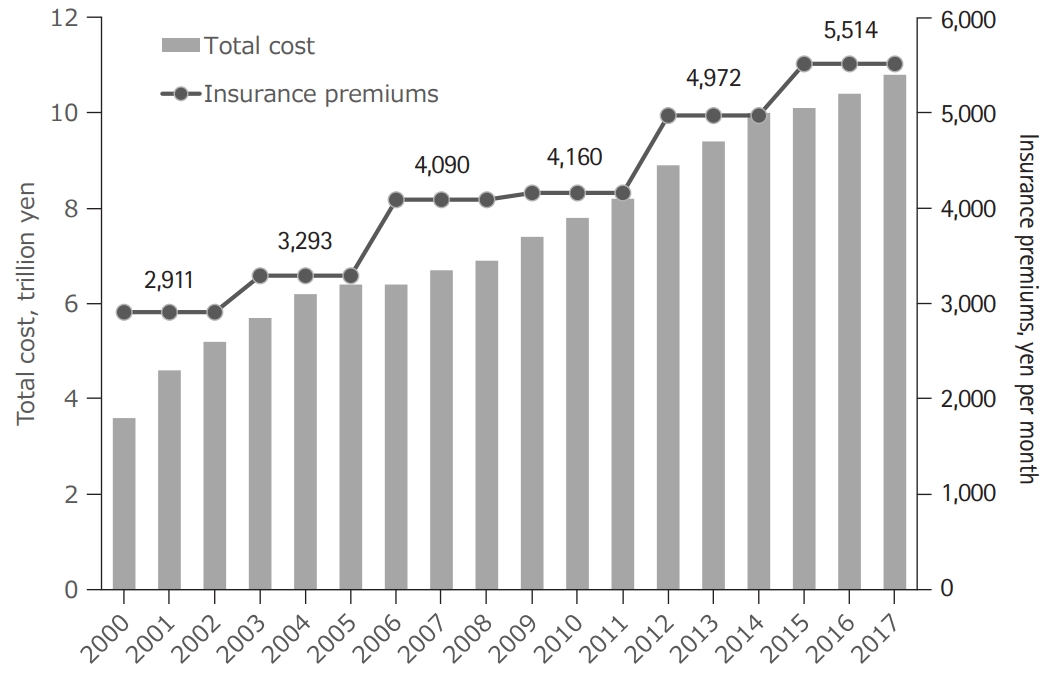

The municipal governments formulate an LTCI service plan that is updated every 3 years. Insurance premiums and copayments are revised according to this plan. As aging proceeds, long-term care expenses have increased from ¥3.6 trillion (US $32.7 billion) in 2000 when the LTCI system was introduced to ¥11.7 trillion (US $106.4 billion) in 2019. This amount is projected to exceed ¥15 trillion (US $136.4 billion) by 2025 (Fig. 3).3) The change affected the financial burden on individuals; premiums increased from ¥2,911 in 2000 to ¥5,514 in 2015, and the copayment rate was increased to 20% or 30% for dependent older adults with moderate income (¥2.8–3.4 million) and high income (¥3.4 million or more). Based on the estimated future Japanese demographic changes, both long-term care costs and premiums are expected to increase; therefore, these revisions aim to maintain the equality and promote the sustainability of the LTCI system. However, it is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain this system owing to the aging population and an increased number of people requiring care and support.

In Japan’s LTCI system, every person aged 65 years or older and middle-aged persons (aged 40–64 years) with specified diseases are eligible for benefits based strictly on physical and cognitive disability. We use category 1 for insured persons aged 65 years or older and category 2 for insured persons aged 40–64 years. LTCI services are provided when persons with category 1 require care or support for any reason and when persons with category 2 develop a specified disease and therefore require care or support.

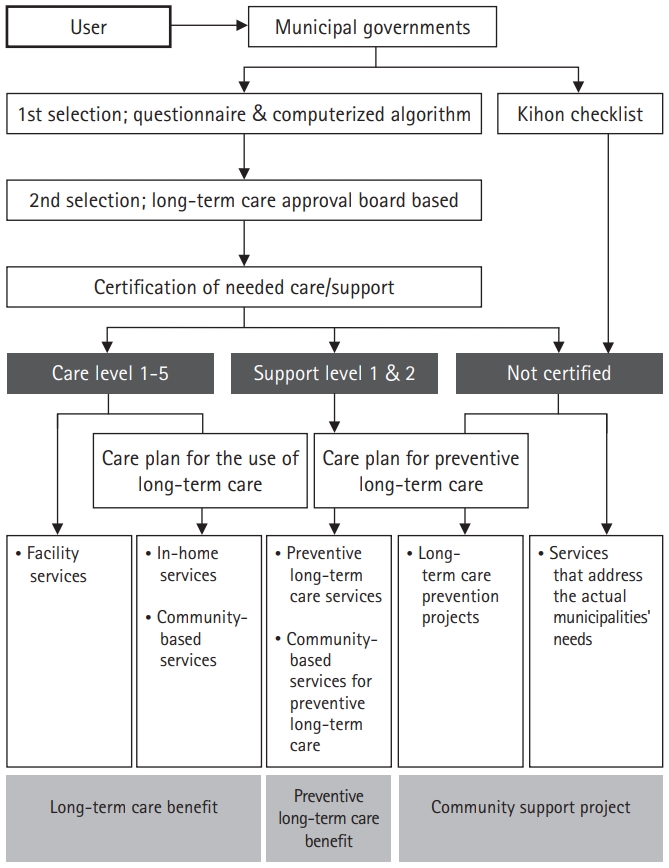

Eligibility is assessed using a 74-item questionnaire based on activities of daily living, followed by a decision made by a long-term care approval board based on the initial computer decision, the home-visit report, and a medical doctor’s opinion. There are seven levels of long-term care that require certificates: support levels 1 and 2 and care need levels 1 (least disabled) to 5 (most disabled).

LTCI services are provided to insured persons who are certified for support or care requirements according to their care needs and certification assessment. The insurance benefits include in-home services (e.g., home visits/day services and short-stay services/care) and services at facilities, including long-term care welfare facilities (also called special nursing homes), long-term care health facilities (also called geriatric health services facilities), and long-term care medical facilities (medical long-term care sanatoriums) without cash benefits or other direct benefits for family caregivers. Dependent older adults can select and use provided facility, in-home, or community-based services according to their care needs and care managers are actively involved in care plans and service arrangements (Fig. 4). Individuals who are not eligible for long-term or support care may utilize preventive care services.

In Japan, future demands for medical care will accelerate the transition to healthcare and nursing care services for dementia, frailty, sarcopenia, and other geriatric syndromes.4) In addition to acute medical care, the provision of healthcare and nursing care should be considered for the convalescent and chronic stages of conditions, which are provided in convalescent rehabilitation facilities and several types of nursing homes. In this environment, it is not sufficient to provide medical care that merely addresses each disease in a fragmented manner for older people. A broad perspective that considers the function of all organs, activities of daily living, frailty, and environmental factors is required. With this in mind, the Japanese government has proposed the establishment of a “Community-based Integrated Care System” by 2025, when baby boomers will be 75 years or older.5) The purpose of this system is to comprehensively ensure the provision of healthcare, nursing care, preventive care, housing, and livelihood support in each community.

Home medical care is the cornerstone of healthcare in a community-based integrated care system; the promotion of this field is undoubtedly important in promoting community-based integrated care. Various home-based services, such as home-visit services and nursing care, play a very important role in community-based integrated care along with home medical care. However, home medical care requires further development by considering future demand. Constructing a comprehensive home medical care system in Japan is a huge challenge and an indispensable milestone for aging.

In 2006, the government implemented measures aimed to identify frail or prefrail older adults, provide early preventive care programs for the prevention of functional decline, and delay dependence on long-term care. Because frail or prefrail older adults have a high risk of disability,6,7) it is important to screen this population early and provide interventions to prevent incident disability. The measure consists of identifying older people with disability risks by screening them using a validated questionnaire, Kihon checklist (Table 1).8,9) Identified frail or prefrail older persons are subsequently referred to no-cost community prevention programs. This prevention program is effective in preventing the progression of frailty and further disability in community-dwelling older adults.10)

However, the utilization of the Kihon checklist was not sufficient to identify individuals at a high risk for disability; additionally, participation in the local intervention programs was quite low. Based on available evidence, the government estimated that approximately 5% of the total older population was at risk and therefore should be the target of preventive care. However, in 2014, by the 9th year of strategy implementation, only 0.8% of older adults had joined the community prevention program, which was unexpectedly low.11) This result was because of the low participation in the screening process for functional difficulties, which was only 34.8% of older people.11) We speculate that physical and environmental barriers and the lack of support to overcome these barriers, such as incentives and transportation, may explain the low participation. In addition, low awareness of disability prevention among general practitioners and the general public might have affected the outcome. The low participation in community prevention programs resulted in limited attributable effect unless researchers committed to the prevention program.12) The government recognized the difficulties in maintaining participants’ motivation and changed its policies for population-based preventive service provisions.

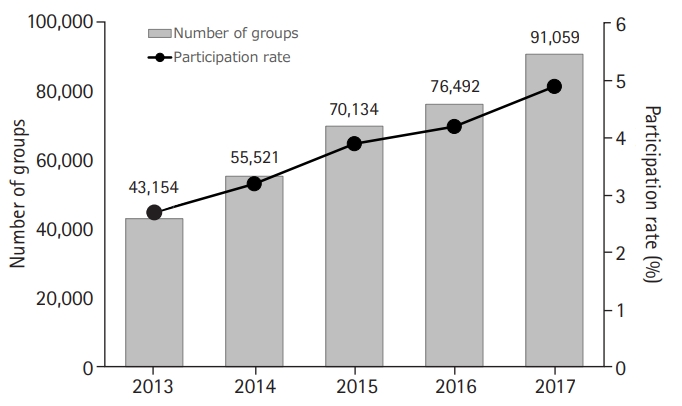

With extensive efforts for disability prevention after the implementation of the LTCI system, public long-term disability prevention plans now focus on promoting social participation and preventing the isolation of older people as isolation is a strong risk factor for disability and mortality. In 2015, the government reformed the Long-term Care Insurance Act by changing its primary strategy for long-term disability prevention from a high-risk strategy to a community-based population strategy. The new strategy aims to build a community that can seamlessly provide preventive, medical, and long-term care and welfare and housing services to all individuals. Based on the population strategy for long-term disability prevention, central and local governments have promoted community activities, such as salons, to facilitate group participation and encourage social activities among older adults. These group activities lead to reduced disability incidence and further long-term care costs in older adults.13,14) Therefore, both the Japanese central and local governments have been promoting community group activities in each community. As a result, the number of groups increased from 43,154 in 2013 to 91,059 in 2017 (Fig. 5).15) Shifting from a high-risk to a population strategy involving multidisciplinary community collaborations has been successful in Japan. For community-based integrated care systems to succeed, collaborations between community members and diverse service providers are mandatory. These collaborations allow community members to create or modify their community welfare services in line with their needs and local situations. Quantitative health equity assessments and visualization of results in an easily understandable manner are also useful for identifying and prioritizing problems and sharing community goals of local actions and policies with service providers and community members.

In 2017, the World Health Organization published the Guidelines on Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) to provide guidance regarding preventing, slowing, or reversing the decline of intrinsic capabilities and maximizing functional abilities of older individuals.16) The guidelines make evidence-based recommendations for the comprehensive assessment of the health status of older people and the delivery of integrated healthcare. Most of the guideline recommendations involve secondary prevention measures, i.e., identifying frail older people and providing them with preventive care. However, as supported by Japan’s experience, secondary prevention measures or screening of frail individuals requires effective screening measures to identify frail individuals, effective interventions to mitigate possible risks, and effective means to deliver interventions to frail individuals. Integrated care for long-term disability prevention should include more community-based interventions. Healthcare professionals and organizations should be actively involved in building local organizational networks to provide such care.

Our approach for disability prevention in our LTCI system remains incomplete and requires further revision. We do not have enough geriatricians and physicians with geriatric practice and need to increase the number of physicians who are interested in frailty prevention for their daily practice. Most of the physicians still take a disease-oriented approach rather than a function-oriented approach for older adults. A gap between healthcare professionals and care workers is another significant issue that needs to be addressed. The Japanese government has introduced 15 questionnaires for the health checkup for older adults aged 75 years or over from April 2020 to identify frail older adults and provide appropriate disability prevention programs in collaboration with public health nurses and primary healthcare physicians. Our approach for disability prevention is still underway; however, we believe that we can increase the awareness of frailty and its prevention in physicians and the general public and change the approach for frailty prevention.

Japan is the most aged country worldwide, and the burden of long-term care is continuously increasing. To minimize the negative effect and maximize the positive effect of aging and to achieve healthy longevity, it is pivotal to increase the quality of a community-based integrated healthcare system and accumulate further evidence on disability prevention in Japan.

Fig. 1.

Changes in the population. Adapted from the Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.1)

Fig. 2.

Japan’s long-term care insurance system in 2018. Adapted from the Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.3)

Fig. 3.

Trends of long-term care total cost and premiums. Adapted from the Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.3)

Fig. 4.

Procedure for use of long-term care insurance. Adapted from the Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.3)

Fig. 5.

Trends of number of community groups and participation rate. Adapted from the Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.15)

Table 1.

Kihon checklist

BMI, body mass index.

Adapted from Arai H, Satake S. English translation of the Kihon Checklist. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15(4):518-9, with the permission of John Wiley & Sons.9)

REFERENCES

1. Cabinet Office. White paper on aging society [Internet]. Tokyo, Japan: Cabinet Office; c2020 [cited 2020 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2018/html/zenbun/s1_1_1.html.

2. Tsutsui T, Muramatsu N. Care-needs certification in the long-term care insurance system of Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:522–7.

3. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. The current and future role of the public long-term care insurance system [Internet]. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; 2018 [cited 2020 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/0000213177.pdf.

4. Arai H, Ouchi Y, Toba K, Endo T, Shimokado K, Tsubota K, et al. Japan as the front-runner of super-aged societies: perspectives from medicine and medical care in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15:673–87.

5. Tsutsui T. Implementation process and challenges for the community-based integrated care system in Japan. Int J Integr Care 2014;14:e002.

6. Yamada M, Arai H. Predictive value of frailty scores for healthy life expectancy in community-dwelling older Japanese adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015 16:1002.e7-11.

7. Yamada M, Arai H. Social frailty predicts incident disability and mortality among community-dwelling Japanese older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19:1099–103.

8. Tsuji T, Kondo K, Kondo N, Aida J, Takagi D. Development of a risk assessment scale predicting incident functional disability among older people: Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2018;18:1433–8.

9. Arai H, Satake S. English translation of the Kihon Checklist. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15:518–9.

10. Yamada M, Arai H, Sonoda T, Aoyama T. Community-based exercise program is cost-effective by preventing care and disability in Japanese frail older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:507–11.

11. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. The survey for implementation of long-term care prevention programs and preventive everyday living support comprehensive programs [Internet]. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; 2014 [cited 2020 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12300000-Roukenkyoku/0000077238_3.pdf.

12. Saito J, Haseda M, Amemiya A, Takagi D, Kondo K, Kondo N. Community-based care for healthy ageing: lessons from Japan. Bull World Health Organ 2019;97:570–4.

13. Yamada M, Arai H. Self-management group exercise extends healthy life expectancy in frail community-dwelling older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:531.

14. Saito M, Aida J, Kondo N, Saito J, Kato H, Ota Y, et al. Reduced long-term care cost by social participation among older Japanese adults: a prospective follow-up study in JAGES. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024439.

15. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Sources from the 76th meeting of the Long-Term Care Insurance Subcommittee of the Social Security Council [Internet]. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; 2019 [cited 2020 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi2/0000184159_00003.html.

16. World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

Related articles in

Ann Geriatr Med Res -

Policies and Transformation of Long-Term Care System in Taiwan2020 September;24(3)