Impact of Motivation for Eating Habits, Appetite and Food Satisfaction, and Food Consciousness on Food Intake and Weight Loss in Older Nursing Home Patients

Article information

Abstract

Background

This study analyzed data from the Long-term care Information system For Evidence (LIFE) database to examine the effects of motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness on food intake and weight loss.

Methods

Of the 748 nursing home residents enrolled in the LIFE database, 336 met the eligibility criteria for this cross-sectional study. Motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness were rated on five-point Likert scales (e.g., good, fair, normal, not so good, and not good). We applied Spearman rank correlation coefficient and multiple regression analyses to analyze the relationships between these three items, daily energy and protein intake, and body weight loss over 6 months.

Results

The mean participant age was 87.4±8.1 years and 259 (77%) were female. The required levels of care included—level 1, 1 (0%); level 2, 4 (1%); level 3, 107 (32%); level 4, 135 (40%); and level 5, 89 (27%). The mean daily energy intake was 28.2±7.8 kcal/kg. The mean daily protein intake was 1.1±0.3 g/kg. The mean weight loss over six months was 1.2±0.7 kg. We observed strong positive correlations among motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness (r>0.8). These three items were significantly associated with higher daily energy intake but not with daily protein intake. Only appetite and food satisfaction were significantly associated with lower weight loss over six months.

Conclusion

The observed associations of appetite and food satisfaction suggest that these factors may be more important to assess than motivation to eat or food consciousness among older adult residents of long-term care facilities.

INTRODUCTION

Nutrition is important for maintaining and improving function in older adults. A meta-analysis reported malnutrition prevalence rates of 28.7% and 29.4% in long-term and rehabilitation and subacute care, respectively.1) Malnutrition is common in older adults requiring long-term care, and a malnutrition-disability cycle may occur, in which malnutrition and disability reinforce each other.2) In patients with stroke and hip fractures requiring inpatient rehabilitation, sarcopenia is common, and activities of daily living (ADL) improve with improved nutritional status.3-5) Rehabilitation nutrition, which combines both rehabilitation and nutritional care management, is important for maximizing function in older adults.6-8) Additionally, poor oral health makes it difficult to regain function in rehabilitation.9,10) Therefore, Japan is promoting the triad of rehabilitation, nutrition, and oral management to improve functioning and prevent disability in the Japanese long-term care insurance system by 2021. Moreover, the Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform 2023, a national policy created by the Japanese Cabinet, states that rehabilitation, nutrition management, and oral management should be coordinated and promoted.11,12) Adequate dietary intake is important because it helps maintain good nutritional status and maintain or improve function.

While appetite is important in nutrition and maintaining function, whether differences in appetite are based on eating motivation, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness remain unclear. Moreover, although aging anorexia is a common and distressing geriatric syndrome, it is underdiagnosed and undertreated in routine clinical care.13) Appetite loss is associated with increased risks of malnutrition, mortality, and decreased muscle strength, as well as decreased physical performance.14,15) Anorexia is a diagnostic criterion for cachexia in Asia.16) Therefore, appetite assessment is necessary in older adults who require long-term care. The Long-term care Information system For Evidence (LIFE) database collects data on nutrition to improve nursing care.17-20) The data collected by the LIFE include motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness. However, the potential differing effects of these items on dietary intake and nutritional status are unknown.

Therefore, this study analyzed data from the LIFE database to examine the effects of eating motivation, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness on food intake and weight loss.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study used data from the LIFE database. The details of the LIFE have been reported previously.17-20) In brief, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare launched the LIFE long-term care insurance service database in April 2021. This database stores information on diseases, physical and cognitive functions, rehabilitation goals and interventions, ADL, instrumental ADL, and nutrition. This database provides feedback to users and facilities and promotes high-quality evidence-based services. In addition, based on the LIFE database, service providers can charge additional fees within the long-term care insurance system. The LIFE data used in this study were stored in the electronic medical record system of Care Connect, Japan. This study used cross-sectional data from 748 nursing home residents enrolled in the LIFE database between April 2022 and March 2023, with consent obtained from the nursing homes.

The inclusion criterion was residents of nursing homes with oral intake only. The exclusion criteria included missing data on oral intake, motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness. The Ethics Committee of Mie University (No. H2022-210) approved the study, which was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its subsequent amendments. Informed consent and approval requirements were waived.21) This study complied the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing in the Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research.22)

The LIFE database includes basic patient information such as age, sex, dementia, Barthel Index, and the requirement for a texture-modified swallowing diet. The motivation to eat refers to the willingness to eat three times a day, avoid leftovers, and maintain and improve health and function. The motivation to eat in the past three days was assessed using a five-point Likert scale: good=1, fair=2, normal=3, not so good=4, and not good=5. Appetite refers to the desire for food. Food satisfaction encompasses satisfaction and preferences regarding taste, quantity, appearance, aroma, deliciousness, and appropriate temperature. These two items were rated individually, and their average was combined into a single response. Appetite and food satisfaction were the ratings for appetite and food satisfaction for the last 3 days, selected from five levels: much (level 1), some (level 2), usual (level 3), not much (level 4), and not at all (level 5). Food consciousness is an interest in choosing and eating an appropriate diet, including a balanced diet, appropriate portion sizes, and disease-specific diets, such as low-sodium diets for hypertension and low-protein diets for chronic kidney disease. Food consciousness in the last 3 days was rated according to five levels: much (level 1), some (level 2), usual (level 3), not much (level 4), and not at all (level 5). Food consciousness includes energy, nutritional balance, taste, appearance, aroma, ingredients, and quantity. Nurses, care managers, or care workers evaluated and entered these ratings into the database during the study period. Nutrient intake and other nutritional parameters were assessed by a nationally certified, registered dietician in Japan. Although training for the LIFE database was not conducted, registered dietitians possessed nutritional knowledge and skills. The LIFE database entry manual was used for data entry. The relationships between motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, food consciousness, daily energy and protein intake in the last three days, and body weight loss over six months were examined.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Parametric data are expressed as mean±standard deviation, while nonparametric data are expressed as medians and interquartile range (IQR). We applied Spearman rank correlation coefficient and multiple regression analyses to investigate the relationships between motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, food consciousness, daily energy intake, daily protein intake, and body weight loss over 6 months. The multiple regression analysis was adjusted for age, sex, presence of dementia, eating independence as assessed using the Barthel Index, and the presence of a texture-modified swallowing diet, which was used to examine the relationship because these factors affect energy intake, protein intake, and body weight loss. Variance inflation factor (VIF) values >10 were considered indicative of multicollinearity. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Among the 748 patients in the LIFE database, after excluding 15 patients without oral intake, two patients with both oral intake and enteral nutrition, and 395 patients with missing data, a total of 336 patients meeting the eligibility criteria were included in the analysis. Nurses, care managers, and care workers entered data for 100, 224, and 10 patients, respectively.

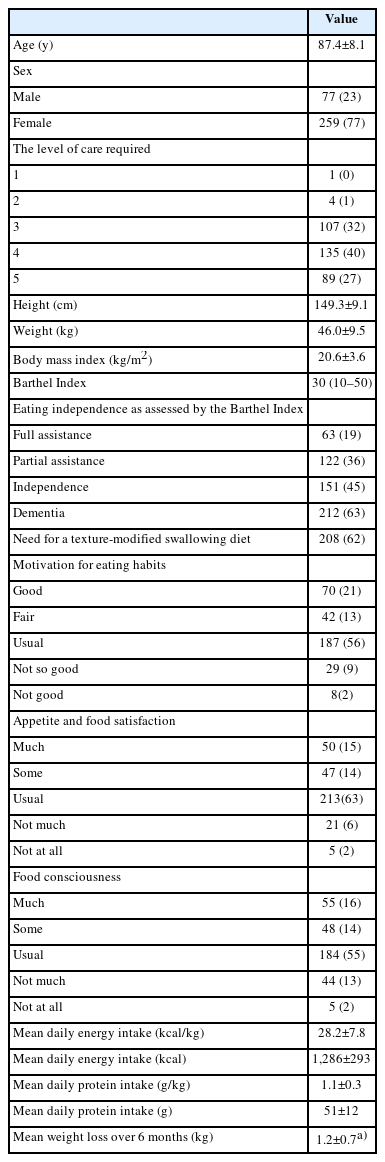

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. The mean age was 87.4±8.1 years, and 259 (77%) were female. The median Barthel Index score was 30 (IQR, 10–50). Most of the responses regarding motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food awareness were “usual,” with no major differences in distribution. Dementia and Alzheimer disease were diagnosed in 212 (63%) and 130 (39%) patients, respectively. The mean daily energy intake, protein intake, and weight loss over 6 months were 28.2±7.8 kcal/kg, 1.1±0.3 g/kg, and 1.2±0.7 kg (n=106), respectively.

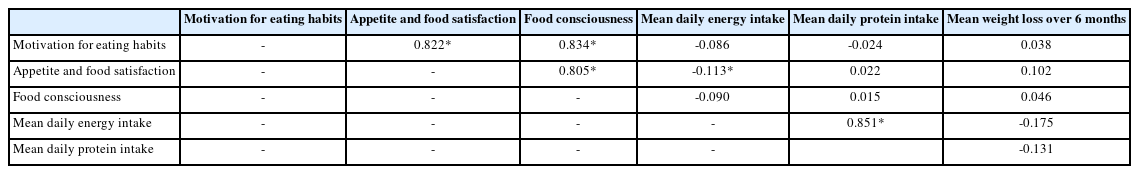

Table 2 shows Spearman rank correlation coefficients. The coefficient value between motivation to eat and appetite and food satisfaction was 0.822, that between motivation to eat and food consciousness was 0.834, and that between appetite and food satisfaction and food consciousness was 0.805, all of which were strongly positively correlated (p<0.001). The Spearman rank correlation coefficients between motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, food consciousness, and daily energy intake showed a weak negative correlation only for appetite and food satisfaction (r=-0.113, p<0.038). We observed no significant correlations of motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness with daily protein intake or weight loss over 6 months.

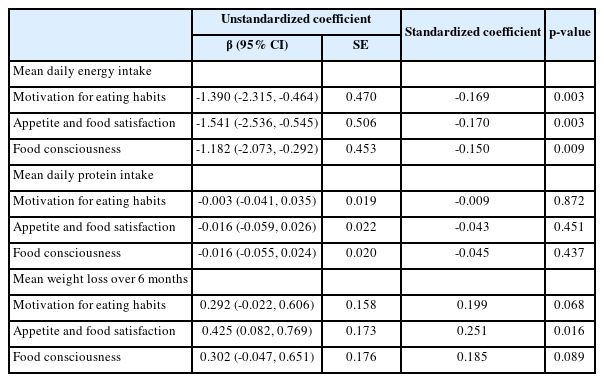

Table 3 presents the results of the multiple regression analysis. After adjusting for age, sex, presence of dementia, eating independence as assessed by the Barthel Index, and presence of a texture-modified swallowing diet, higher motivation to eat, higher appetite and food satisfaction, and higher food consciousness were all significantly associated with more daily energy intake, but not with daily protein intake. In contrast, only higher appetite and food satisfaction were significantly associated with lower weight loss over 6 months. All VIF values in the multiple regression analysis ranged from 1.0 and 1.6. Therefore, our multiple regression analysis did not reveal multicollinearity issues.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the effects of motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness on food intake and weight loss. Motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness were associated with daily energy intake but not with daily protein intake. Appetite and food satisfaction were significantly associated with weight loss over 6 months. Motivations to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness were strongly positively correlated.

Regarding the association of motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness with daily energy intake but not with daily protein intake, a previous systematic review reported that appetite scores were not correlated with energy intake in 51.3% of studies, regardless of participant age or sex.23) Although these factors were associated with daily energy intake, the correlation was weak or insignificant according to the Spearman rank correlation coefficients. Although appetite should be assessed, factors other than appetite may have a greater influence on energy intake. Protein supplementation may suppress appetite; however, a previous meta-analysis reported that it had either a positive or no effect on total energy intake in older people.24) Moreover, appetite does not necessarily correlate with protein intake in older adults.25) In older adults with decreased appetite, energy intake is likely to be lower than protein intake; therefore, it may be better to first recommend increased energy intake. However, monitoring protein intake may be important in nursing home residents with good appetite because protein intake does not increase with appetite. If appetite is good but protein intake is inadequate, protein intake should be increased.

Appetite and food satisfaction, but not motivation to eat or food consciousness, were significantly associated with weight loss over six months. Motivation to eat can be improved with interventions.26) While interventions to improve food consciousness can increase interoceptive sensitivity and exteroceptive expression,27) these may not be enough to prevent weight loss. Age-related anorexia is also associated with physical frailty and weight loss.28,29) Food satisfaction is associated with oral frailty in community-dwelling older people.30) Moreover, oral frailty is a risk factor for physical frailty and may lead to weight loss.31) Therefore, the assessment of appetite and food satisfaction may be more important than that of the motivation to eat or food consciousness.

We observed strong positive correlations among motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness. Although these are different concepts, the strong correlations suggest much common ground. As the LIFE database has many input items and a high input burden, the number of input items should be reduced if possible. The results of the present study showing strong correlations suggest that if appetite and food satisfaction are recorded, the other two items may not be required.

This study has several limitations. First, not all items related to dietary intake and weight loss were adjusted in the multivariate analysis. The LIFE database contains many items; however, including more items in the multivariate analysis would increase the number of cases excluded because of missing values. Second, many of the patients had dementia and may not have responded appropriately to questions about motivation to eat, appetite, food satisfaction, and food consciousness. Third, the multiple regression analysis included the presence of dementia rather than its severity. The LIFE database lacks data on the severity of dementia; however, it did include the “criteria for determination of the daily life independence level of older adults with dementia,” which comprises eight steps. We conducted multiple regression analyses using these criteria instead of the presence of dementia. Nevertheless, the results were similar, and neither the criteria for determining the daily life independence level of older adults nor the presence of dementia was independently associated with energy intake, protein intake, or body weight loss. Fourth, because the LIFE database contained only cross-sectional data, we were unable to perform a longitudinal study, and the causal relationships were uncertain. Future studies should use the LIFE database that contains longitudinal data.

In conclusion, higher motivation to eat, appetite and food satisfaction, and food consciousness were significantly associated with more daily energy intake but not with daily protein intake. Only higher appetite and food satisfaction were significantly associated with lower weight loss over 6 months. Motivation to eat, appetite, food satisfaction, and food consciousness were strongly positively correlated. Further longitudinal studies are needed to examine the relationship of appetite and food satisfaction with weight loss, ADL, oral status, and swallowing function to determine whether some items can be removed from the LIFE database.

Notes

We would like to thank Care Connect Japan for providing the LIFE data.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The researchers claim no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

Ryo Momosaki was funded by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 22H03311).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, HW; Data curation, HW, SK, RM; Funding acquisition, RM; Investigation, HW; Methodology, HW, RM; Project administration, RM; Supervision, SK, TI, KS, HT; Writing-original draft, HW; Writing-review & editing, SK, TI, KS, HT, RM.