Clostridium tetani Infection in a Geriatric Patient: Do Not Let Your Guard Off!

Article information

Abstract

Tetanus is an infectious disease caused by Clostridium tetani toxin. Although easily preventable through vaccination, over 73,000 new infections and 35,000 deaths due to tetanus occurred worldwide in 2019, with higher rates in countries with healthcare barriers. Here, we present a clinical case of C. tetani infection in an 85-year-old patient. Patient robustness and high functional reserve before infection are favorable predictors of survival for an otherwise fatal disease. However, the patient did not experience any severe complications. Therefore, this report is a strong call for tetanus vaccination.

INTRODUCTION

Tetanus is a non-communicable disease caused by the tetanospasmin neurotoxin produced by the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium tetani. The condition presents as spastic paralysis that spreads from the head and neck to the trunk and limbs.1) Global incidence and mortality depend on the barriers to care and availability of vaccines; however, even with proper care, mortality is up to 50% in adults.1) Herein, we describe the tetanus sequelae in an 85-year-old survivor. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publishing this case report.

CASE REPORT

An 85-year-old man was transferred from the geriatric medicine unit of our tertiary hospital to our rehabilitation unit and underwent intensive treatment for the sequelae of C. tetani infection. He is a farmer leading an active lifestyle. His past medical history included atrial fibrillation (AF) and benign prostatic hypertrophy.

Two months prior, he was admitted to a local hospital because of trismus and hypertonia after injuring his leg while working on his farm. Since the clinical findings and medical history were strongly suggestive of C. tetani infection, he began immediate treatment with immunoglobulins, tetanus vaccination, and metronidazole for ten days (Fig. 1). He was transferred to our intensive care unit (ICU), where he underwent tracheostomy, mechanical ventilation, and vasoactive support owing to respiratory failure. The seizures were treated with baclofen, midazolam, and diazepam. Electroencephalography revealed severely slow cerebral activity. Due to worsening respiratory function, opacity on chest radiography, and peripheral leukocytosis due to possible ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), blood cultures and tracheal secretion samples were sent for laboratory analysis. The tracheal secretions tested positive for Klebsiella pneumoniae and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA); therefore, antibiotic therapy with piperacillin-tazobactam was prescribed (Fig. 1).

Timeline of infections and duration of antibiotic treatments. AMC, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; AMK, amikacin; ATM, aztreonam; BSI, bloodstream infection; CAS, caspofungin; CFZ, cefazolin; CST, colistin; CZA, ceftazidime-avibactam; CU, cardiac intensive care unit/cardiology unit; FDX, fidaxomicin; FEP, cefepime; ICU, intensive care unit; KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase; LZD, linezolid; MDR, multidrug resistant; MEM, meropenem; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; MTZ, metronidazole; R, resistant; RTI, respiratory tract infection; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; UTI, urinary tract infection; VAN, vancomycin; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

The patient was later moved to a geriatric unit in a coma and breathed spontaneously on 4 L/min of supplemental oxygen via a tracheal cannula. After three days, the antibiotic therapy was switched to linezolid (14 days) due to VAP exacerbation, and combined treatment with meropenem for 17 days was prescribed after septic shock occurred (Fig. 1). The patient gradually awoke, and the feeding tube was removed. He developed cholestasis and acute edematous pancreatitis; however, the endoscopic treatment got postponed due to spontaneous recovery. Urinary tract infection caused by the multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) K. pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Enterococcus faecalis was treated with colistin and amoxicillin-clavulanate for 1 week (Fig. 1). Eventually, his clinical condition improved, and he was considered eligible for rehabilitation.

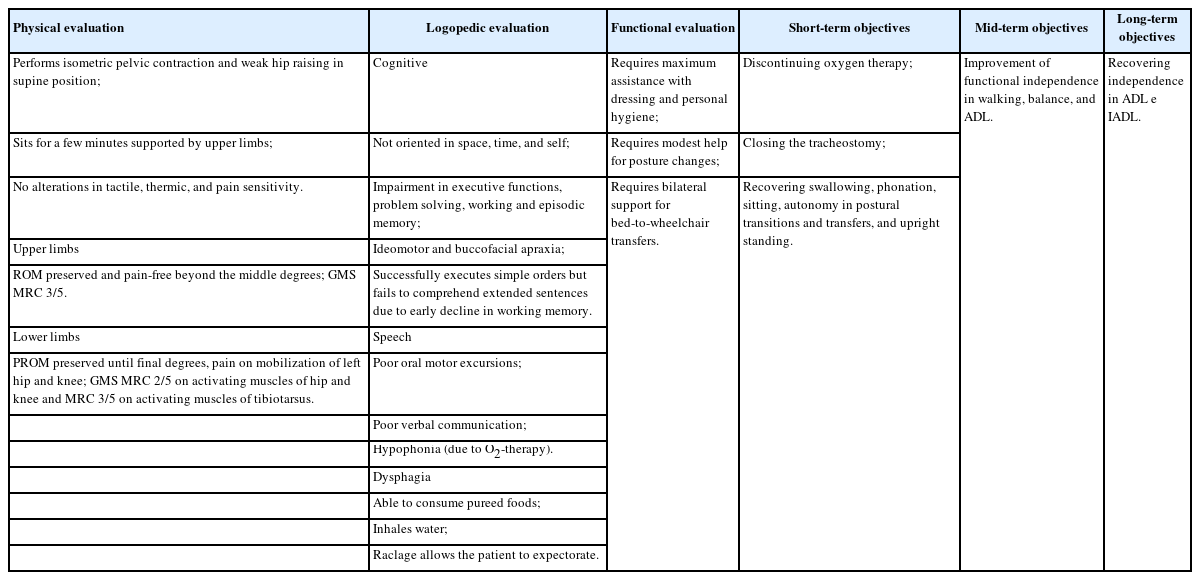

In our unit, the patient was placed in MDRO isolation. He still required tracheal supplemental oxygen (1 L/min) and a bladder catheter and developed pressure ulcers on the right (unstageable) and left (stage II) heels, sacrum (stage II), and right elbow (stage III). He was sarcopenic and had low handgrip strength (9.9 kg) and appendicular skeletal mass (ASM, 16.9 kg). The rehabilitative evaluations are presented in Table 1.

On the first day, the patient underwent rehabilitation with good compliance. However, Clostridioides difficile infection occurred, and oral vancomycin was prescribed for 10 days. After 3 days, he presented with AF with a third-degree atrioventricular block (heart rate, 30 beats/min) without secondary bradyarrhythmia. The patient was transferred to our hospital’s cardiac ICU to undergo single-chamber pacemaker implantation and presented with hyperkinetic delirium during the postoperative course. Two days later, the patient was transferred to our hospital. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection was treated with ceftazidime-avibactam and amikacin for 1 week (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, on a routine nasopharyngeal swab, the patient tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The patient was treated with remdesivir for 3 days and placed on droplet isolation. The following day, a second recurrence of C. difficile occurred; therefore, he was transferred to a geriatric medicine unit. The infection was successfully treated with fidaxomicin for ten days.

Two days after completing treatment for the recurrence of C. difficile, he presented with bloodstream infection due to Candida parapsilosis (fluconazole-resistant), MSSA, and Candida tropicalis originating from the intravenous catheter; after replacing the infected catheter, it was treated with caspofungin and cefazolin for 17 days. After 10 days, the patient presented with a bloodstream infection caused by P. aeruginosa. Antibiotic treatment with piperacillin-tazobactam was prescribed and eventually shifted to aztreonam and ceftazidime-avibactam owing to evidence of antibiotic resistance from the antibiogram. After 4 days, owing to the improvement in clinical condition, the antibiotic was shifted to cefepime for 10 additional days (Fig. 1).

During the last months of hospitalization, tracheostomy closure was performed by an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist and pulmonologist. Throughout the hospitalization, nutritional supplementation was prescribed to manage malnutrition and sarcopenia. From the motor point of view, although intensive rehabilitation was compromised due to the large number of infectious (Fig. 1) and non-infectious complications, the patient continued to undergo short physiotherapy sessions according to the changes in his clinical condition.

At discharge, the patient was able to perform postural transition with assistance. Motor and respiratory reconditioning continued at discharge. From a motor point of view, posture transition training and aided transfers, axial stability, and balance improvement exercises, with the primary goal of achieving a standing position, were prescribed. From a respiratory perspective, breath-movement coordination exercises, thoracic expansion and girdle opening exercises, and inhalation-exhalation exercises were recommended. Wheelchairs and walkers were recommended for the current mobility deficit on short and medium trips and to facilitate safe postural transitions. Rehabilitation, ENT, and geriatric follow-up evaluations were recommended.

DISCUSSION

This report describes the sequelae of tetanus in a geriatric patient. Tetanus is an often-fatal disease accompanied by several complications and is even more severe in geriatric patients.2,3) Our patient developed respiratory failure, coma, VAP, septic shock, healthcare-associated infections (HAI), acute sarcopenia, life-threatening bradyarrhythmia, and pressure ulcers. The electroencephalogram and cognitive function assessment results (Table 1) raised the possibility of incident dementia, likely with vascular or mixed etiology. AF also plays a role in cognitive decline,4) and ICU admission may increase the risk of dementia.5,6) However, as no specific examinations were performed, this diagnosis cannot be validated. Furthermore, HAI, delirium, and sarcopenia were associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients.7-11)

This case demonstrates the catastrophic effects of an otherwise preventable disease. In 2019, more than 73,000 new infections and 35,000 deaths due to tetanus occurred worldwide, with the highest incidence rates reported in Nepal, Eritrea, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.12,13)

Maternal and neonatal tetanus are public health concerns in developing countries12); in higher-income countries, aged individuals are susceptible to both cases and death.1) Although vaccination does not affect the environmental distribution,14) serum antibody levels decrease with aging.15,16) Furthermore, the possibility that older adults may not have completed their primary vaccination cycle should not be overlooked.17) Vaccines have reduced tetanus incidence and mortality by up to 89% in the last century.12) After the primary cycle,1) periodic booster shots are recommended for adults.13) The current state-of-the-art tetanus vaccination involves three vaccine doses at the 3rd, 5th, and 11th months of life; booster doses at 7 and 14 years of age; further booster doses every ten years.18) Diagnosis of C. tetani infection is based on clinical examination, medical history, and epidemiology. The differential diagnosis of trismus includes local oral or pharyngeal conditions, and the differential diagnosis of muscular spasms includes strychnine poisoning and iatrogenic causes.18) In the event of a risk of C. tetani infection, the procedure envisages the administration of a vaccine dose plus the simultaneous administration of immunoglobulins if the vaccine status is absent or uncertain or if 10 years have elapsed since the last booster vaccine was administered. If the last dose of vaccine was administered <5 years prior, no further booster vaccine is required; on the contrary, after the 5th year of administration, a booster dose is recommended without simultaneous administration of immunoglobulins. Other steps for infection management include endotracheal intubation and early tracheostomy for airway protection, diazepam or midazolam administration to eliminate reflex spasms, surgical debridement of infected tissues, and antibiotic therapy with metronidazole or benzylpenicillin for 7–10 days.18,19)

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has deeply affected people’s lifestyles, especially those of older and frailer individuals.20-22) The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused a dramatic decrease in compulsory vaccination among children.23-25) Although no studies have been conducted on vaccination shifts in older individuals, the effect of the pandemic on health service accessibility in older persons has been widely documented.26,27)

Therefore, this study is intended to be a strong call for tetanus vaccination, especially in geriatric patients. In addition, we hope that health can become a universal right.

Notes

The authors would like to thank all the medical doctors, nurses, unlicensed assistive personnel, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and all the professionals who have been involved and are still involved in the management of this highly complex case. We also thank Fabio Zeoli, Rocco Mastromartino, Giacomo Piaser Guerrato, and the people of the Medical Research Opportunities Mentoring Program (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy) for allowing many undergraduate students into the world of medical research and guiding them through the writing of scientific articles.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The researchers claim no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, SC, LG, EDA; Methodology, LG, LM; Validation, EDA, FI; Investigation, AP, FA, SC, RR, FI, FMP; Supervision: LG, LM, FL; Writing–original draft, AP, SC; Writing–review & editing, SC, EDA; Visualization, AP, SC.