Very Late-Onset Schizophrenia-Like Psychosis: A Case Report and Critical Literature Review

Article information

Abstract

Late-life psychosis presents a challenge, wherein a wide range of differential diagnoses should be considered. Very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis (VLOSLP) is a nosological entity that remains a conundrum. We provide a comprehensive literature review on the neurobiological underpinnings of VLOSLP. We describe a case that typifies the clinical presentation of VLOSLP. Although not pathognomonic, certain features, namely the two-stage progression of psychotic episode, partition delusions, multimodal hallucinations, and absent formal thought disorder or negative symptoms, are quite suggestive of VLOSLP. Several medical causes that might cause late-life psychosis, including neuroinflammatory/immunology diseases, were ruled out. Neuroimaging revealed basal ganglia lacunar infarctions along with chronic white matter small-vessel ischemic disease. The diagnosis of VLOSLP is based on clinical evidence, and the aforementioned clinical features support this diagnostic hypothesis. This case adds to the growing body of evidence pertaining to the relevance of cerebrovascular risk factors in the pathophysiology of VLOSLP, alongside age-specific neurobiological processes. We hypothesized that microvascular brain lesions disrupt the frontal-subcortical circuitry and uncover other core neuropathological processes. Future research should focus on identifying a specific biomarker that would allow clinicians to more accurately diagnose VLOSLP, differentiate it from other overlapping clinical entities such as dementia or post-stroke psychosis, and provide a tailored treatment for the patient.

INTRODUCTION

Late life onset of psychosis causes challenges in its diagnosis owing to the array of neurobiological processes that occur in the aging brain and medical and neurological illnesses that may emerge with advanced age. The nosology and pathophysiological underpinnings of very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis (VLOSLP) remain unclear. Both neurodegenerative1) and cerebrovascular processes have been proposed, given the common neuroimaging findings of white matter hyperintensity, particularly in the periventricular regions.2,3) Owing to the lack of specific biomarkers, diagnosis is based on clinical evidence, implying the importance of a thorough anamnesis and diagnostic workup.

CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old retired female patient with several cerebrovascular risk factors, including a history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, mild cognitive decline, and an ischemic stroke that had occurred more than 3 years ago with grade 4 hemiparesis on the right side and hearing loss as sequelae, was admitted to our psychiatric ward because of a psychotic episode with a two-stage progression. Initially, the patient manifested persecutory and partition delusions, in which she believed that a TV journalist could transgress the walls and pull her to the TV scene. After 6 months, the delusional symptoms became more striking and were accompanied by multimodal hallucinations, comprising complex visual hallucinations (scenic, lilliputian, and holocampine) and elementary auditory, cenesthetic, olfactory, and gustatory hallucinations, which profoundly impacted her daily life and well-being. No negative symptoms or formal thought disorders were observed.

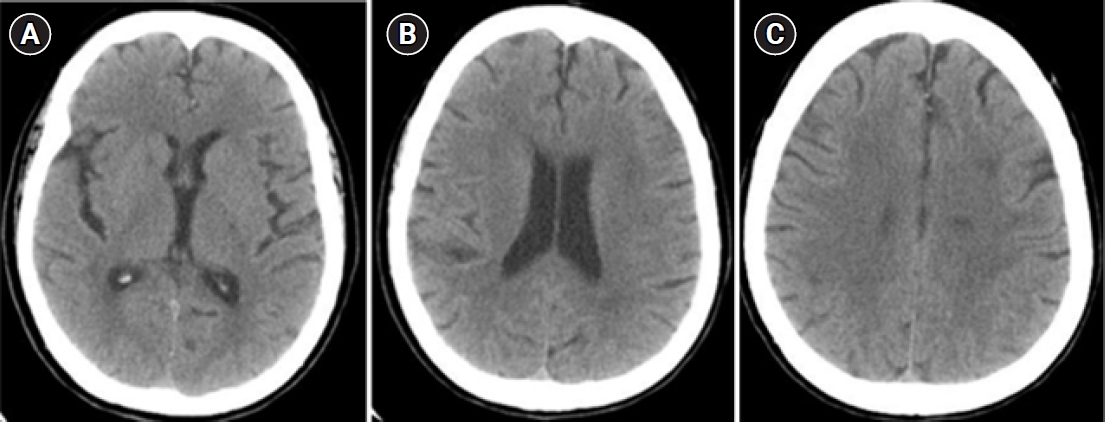

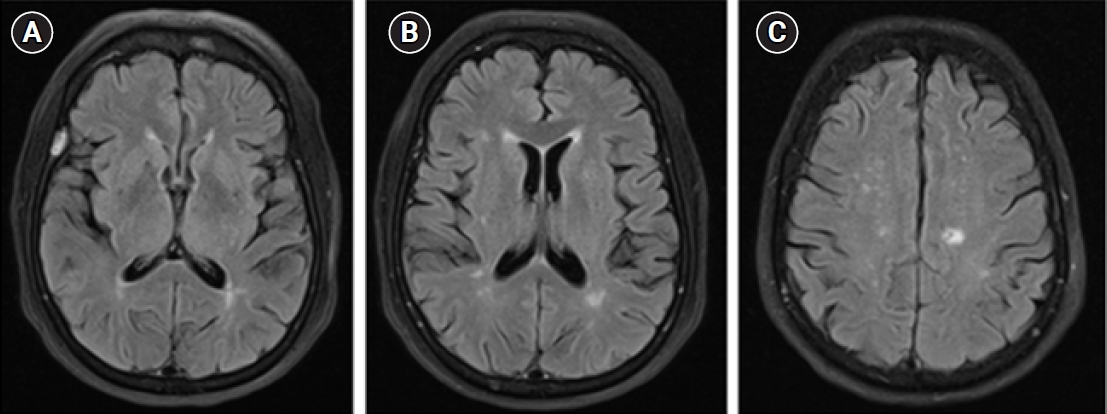

Hematological and biochemical screening revealed normal thyroid function and folic acid and cyanocobalamin levels. Serological tests were negative for venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and C, and transglutaminase antibodies. Neuroimaging revealed chronic microangiopathic cerebral disease with lesions in the periventricular and deep subcortical white matter regions along with deep cerebral infarct lesions in the left centrum semiovale and basal ganglia, encompassing the bilateral thalamic and striatocapsular infarctions (Fig. 1, 2).

Computerized tomography (CT) scan showing cerebral small vessel disease, with bilateral thalamic and striatocapsular infarctions (A) and multiple hypodense lesions in the periventricular and deep subcortical white matter regions (B and C).

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (4 years before the hospitalization in a psychiatric ward) revealing multiple hyperintensities in the periventricular (A and B), and subcortical frontoparietal white matter regions, alongside a gliotic lesion in the left centrum semiovale (C).

Electroencephalography results were normal. Neuropsychological examination revealed mild-to-moderate impairments in the working memory, sustained attention, executive function, abstract thinking, and visuospatial ability. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score was 20/30.

Treatment with risperidone and olanzapine was unsuccessful, and clinical improvement was observed after initiating clozapine treatment. As the psychotic symptoms improved, cognitive deficits also improved (MMSE score of 24/30). The patient was discharged with attenuated psychotic symptoms. During follow-up in psychiatric appointments throughout 1 year, clozapine dose was titrated up to 1,000 mg/day and combined with aripiprazole (10 mg/day) and amisulpride (50 mg/day). Mild improvement in the psychotic symptoms was observed, albeit without remission.

Verbal consent is obtained from the patient's relatives because the patient has deceased.

DISCUSSION

This clinical presentation of a two-stage progression psychotic episode, with partition delusions and multimodal hallucinations in the absence of formal thought disorders and negative symptoms, is typical of a VLOSLP.4) Several medical causes, including celiac disease, which has the second highest incidence in later life, were ruled out.

Cognitive deficits are usually present in VLOSLP, especially in the learning, abstraction, and cognitive flexibility domains.5,6) It is debatable whether our patient’s cognitive impairment could stem from prior cerebrovascular events, pathophysiological processes underlying VLOSLP, or both. Almost half of VLOSLP patients develop dementia within 5 years.7,8) However, cognitive impairment is common even in patients with VLOSLP who do not develop dementia.7) Therefore, it remains controversial whether the propensity to develop dementia is a true characteristic of VLOSLP or reflects an initial misdiagnosis. In this context, VLOSLP should increase the index of diagnostic suspicion of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), in which complex visual hallucinations are a typical early presenting feature and may co-occur with hallucinations in other sensory modalities and systematized delusions throughout its clinical course. A recent study suggested that the presence of psychomotor slowing and visual hallucinations might constitute a prodromal manifestation of DLB in cases wherein a clinical picture suggestive of VLOSLP is present, whereas the cingulate island sign in the single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) scan is an indicative biomarker of DLB.9) However, clinical conditions characterized by partition delusions and multimodal hallucinations are uncommon. Other clinical cues that point to the diagnosis of DLB include the presence of REM behavior disorder, which is a harbinger of alpha-synucleinopathy that may be present approximately one decade before cognitive impairment; a heightened sensitivity to antipsychotic effects; parkinsonism; and a dopamine transporter scan (DaTscan) showing unraveling striatonigral degeneration.

Some studies have suggested a specific neuropathology for VLOSLP: tauopathy restricted to the limbic regions.2) In addition, several cumulative age-specific neurobiological processes, such as subclinical neurodegeneration, accelerated white matter loss, and a decline in estrogen levels, lead to a mesolimbic hyperdopaminergic state, impaired neuroplasticity, immunosenescence, and neurovascular damage, which may have contributed to VLOSLP. Estrogen decline affect the expression and function of dopamine receptors and transporters and has detrimental effects on neuroprotective factors via genomic mechanisms and epigenetic modifications and on the cerebrovasculature, impairing vasodilatory mechanisms.10,11) Moreover, preclinical models of schizophrenia have suggested that estradiol ameliorates positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms.10) More recently, the role of immunosenescence, which encompasses the priming of microglial cells to produce an amplified inflammatory response to brain insults, has been posited in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia-like psychosis with late-life onset, in which an enhanced neuroinflammatory response mediates neurodegeneration, white matter alterations, aberrant synaptic pruning, and neurogenesis inhibition.12)

Based on these factors, the relevance of cerebrovascular disease in the aging brain has been widely suggested, with white matter hyperintensities occurring almost three-fold more frequently in patients with VLOSLP than that in patients with classic early-onset schizophrenia within the same age group.3) Neuroimaging studies have shown that lacunar infarction in the basal ganglia, along with chronic white matter small vessel ischemic disease, may be the underlying pathophysiology of psychosis via the disruption of frontal-subcortical pathways.13,14) Nevertheless, the interval between stroke and emergence of psychosis in our patient was nearly 3 years, which is an extremely long period compared with that in the previously reported cases of post-stroke psychosis, which usually resolves completely within a few months.15) Evidence suggests that a high burden of vascular factors is associated with late-life psychosis in patients with cognitive impairment, regardless of the presence of cerebrovascular lesions.16) Long-term hypertension is associated with microstructural white matter abnormalities. Several studies have demonstrated the association between hypertension, white matter lesions, and cognitive decline.17,18) Cognitive decline and VLOSLP are more strongly associated with periventricular white matter hyperintensities than with subcortical brain infarctions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).2,3,18) Additionally, several studies have suggested an association between estrogenic receptor polymorphisms and vascular cognitive impairment.11)

This case report adds to the growing body of evidence regarding the relevance of cerebrovascular risk factors, including hypertension, basal ganglia infarctions, and microvascular brain lesions, in the pathophysiology of VLOSLP. These factors may disrupt the frontal-subcortical circuitry and neurobiological processes that occur in the aging brain, with a possible limbic tauopathy occurrence. Additionally, neurosensory impairment and psychosocial aspects, such as retirement and social isolation, are well-known predisposing factors of late-life psychosis.

In conclusion, the neurobiological underpinnings of VLOSLP are complex and multifaceted and may result from an interplaying array of age-specific cerebral alterations. More systematized studies are needed, including neuropathological and neuroimaging studies, such as SPECT and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, to pinpoint specific biomarkers, which would elucidate the role of these neurobiological factors and stratify them as core etiologic factors or as trigger factors. Moreover, identifying a specific biomarker would facilitate clinicians to more accurately diagnose VLOSLP, differentiate it from other overlapping clinical entities, such as dementia or post-stroke psychosis, and provide a tailored treatment for the patient.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The researchers claim no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, JR; Supervision, FMP; Writing-original draft, JR; Writing-review & editing, FMP.