Development of a Tool to Measure Compliance with Infection Prevention Activities Against Emerging Respiratory Infectious Diseases among Nurses Working in Acute Care and Geriatric Hospitals

Article information

Abstract

Background

This study developed a preliminary instrument to measure nurses’ infection prevention compliance against emerging respiratory infectious diseases and to verify the reliability and validity of the developed instrument.

Method

The participants were 199 nurses working at a university hospital with more than 800 beds and two long-term care hospitals. Data were collected in May 2022.

Results

The final version of the developed instrument consisted of six factors and 34 items, with an explanatory power of 61.68%. The six factors were equipment and environment management and education, hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette, infection risk assessment and flow management, protection of employees in contact with infected patients, ward access management of patients with infectious diseases, and wearing and removing personal protective equipment. We verified the convergent and discriminant validities of these factors. The instrument's internal consistency was adequate (Cronbach’s α=0.82), and the Cronbach’s α of each factor ranged from 0.71 to 0.91.

Conclusion

This instrument can be utilized to determine the level of nurses’ compliance with infection prevention activity against emerging respiratory infectious diseases and will contribute to measuring the effectiveness of future programs promoting infection-preventive activities.

INTRODUCTION

With the global spread of the coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19), Korea has reported 22,701,921 cumulative cases and 26,332 deaths as of August 25, 2022.1) COVID-19 is mainly transmitted through contact with aerosolized droplets produced when infected patients cough, sneeze, or converse. Personal hygiene such as hand hygiene and social distancing are required infection prevention activities to prevent the spread of such infectious diseases.2,3) Owing to the nature of respiratory viruses such as COVID-19, infections within hospitals result in worse outcomes than social infections because hospitals are largely occupied by older adult patients, and patients with underlying conditions or immunodeficiency rather than healthy individuals. Therefore, preventing the spread of respiratory infectious diseases is more challenging in hospitals, and infection control is crucial.4)

Infection prevention activity refers to the extent to which isolation guidelines are followed to prevent infection transmission in hospitals per standard precautions and transmission-based precautions.5) These activities protect patients, family members, and healthcare professionals from contracting infectious diseases, which is critical because infections not only cause the infected individual’s health to deteriorate but also spread diseases to other patients with weakened immunity. Furthermore, the isolation of healthcare personnel to infections can result in gaps in healthcare.6)

In particular, the subjects of long-term care services are older adult patients with geriatric or other underlying diseases who are at a high risk of infection.7) Thus, infection control by healthcare professionals is also essential in acute care hospitals and long-term care facilities.8)

The harmful effects of healthcare-related infections can be reduced by accurately understanding the standard precautions and complying with infection prevention activities.9-11) When suspecting or confirming an infectious disease in the event of an emerging respiratory infectious disease, such as the current COVID-19, contact precautions, droplet precautions, and air bone precautions based on the transmission route of the emerging respiratory infectious disease should be applied along with standard precautions.9,10)

Enforcing compliance with such infection prevention activities necessitates measuring the level of practice and ensuring their accurate implementation according to the guidelines. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses’ infection-prevention activities have increased owing to increased awareness of these measures. These include wearing masks, hand hygiene, and visitor management in healthcare facilities.12) Modified and supplemented versions of existing instruments or newly developed instruments targeting novel influenza,13) Middle East respiratory syndrome,14,15) and COVID-1916-18) are currently being utilized. However, because researchers have developed instruments based on the guidelines for each type of emerging respiratory infectious disease, the reliability and validity of each tool vary and pose difficulties in comparing study results. In particular, infection control guidelines continuously change throughout a pandemic; for example, for COVID-19,12) a new reliable instrument must be developed that reflects the updated guidelines to ensure compliance with infection prevention activities among healthcare professionals.

First, through literature reviews and focus group interviews (FGIs), this study developed a preliminary instrument to measure nurses’ level of compliance with infection prevention activities against emerging respiratory infectious diseases. We then verified the reliability and validity of this preliminary instrument.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This methodological study developed and measured the validity and reliability of an instrument to measure nurses’ compliance with infection prevention against emerging respiratory infections. The process consisted of instrument development and instrument evaluation stages.

Instrument Development

We reviewed the infection control guidelines and instruments used in previous studies by searching the Research Information Sharing Service (RISS), Korean Studies Information Service System (KISS), and PubMed databases to identify relevant articles indexed from December, 2000 to December 2021. The search strategies were adapted to each database and included terms such as “emerging infectious diseases,” “infection prevention activity compliance,” and “nurses.”

An FGI was conducted with five nurses working in pulmonary units, internal medicine intensive care units, emergency departments, outpatient pulmonology departments, and infection prevention and control departments to reflect the nurses’ occupational characteristics. The participants of the FGI were briefed regarding the study and asked to provide informed consent. Questions related to compliance with infection prevention activities against new respiratory infectious diseases were notified in advance to provide time for the participants to prepare their answers to the questions before the interviews. On the day of the FGI, the interview lasted approximately 2 hours after providing the participants with a description of the study and obtaining their written consent, including the recording of the interview. The interview was conducted until no new statements were found. The researcher took field notes and transcribed the contents of the interview along with recording the interview. The participants were questioned about the activities, tasks, and difficulties related to responding to emerging respiratory infectious diseases as follows: “Please tell us about your activities, work, and experience in responding to new respiratory infectious diseases in your place of work,” “What are the challenges of nursing and responding to new respiratory infectious diseases in medical institutions?” and “What measures are medical institutions taking to prevent and manage new respiratory infectious diseases?”

Sentences containing meaningful content related to compliance with infection prevention activities against emerging infectious diseases were derived from the literature review and the FGI. The factors were identified by grouping them into similar topics. Eight experts, comprising three infection control nurses, three professors of nursing with infection control nursing licenses, and two instrument development specialists, verified the content validity index of the questions derived from the literature review and the FGI. To investigate the opinions on the composition of the questions, such as the readability, ambiguity, and terminology, a preliminary survey was conducted on 10 nurses working in medical institutions, including four in general wards, one in an emergency unit, one in an outpatient department, and one in an infection prevention and control department.

Instrument Evaluation

Data were collected from 222 nurses to verify the item analysis, exploratory factor analysis, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability of the developed preliminary instrument.

Data collection

Because the estimated number of cases necessary for the verification of the tool was approximately 5–10 times the total number of items in the developed instrument,19) 200 cases, which is five times the number of preliminary questions developed in the study of 40 items, were required. A total of 222 individuals were recruited, accounting for a 10% dropout rate. The sample consisted of 122 nurses from a university hospital with over 800 beds in Daejeon City and 100 nurses working at two long-term care hospitals in Seoul Metropolitan City. The inclusion criteria for the study were limited to nurses with a total work experience of 12 months or more to ensure participants with a variety of nursing experiences, except for department heads, who did not participate in patient care in person. A total of 222 questionnaires were collected, of which 199 were used for the final analysis, excluding 23 cases with missing data (10.4% dropout rate).

Before the survey, the participants were briefed regarding the purpose of the study, autonomy regarding participation and withdrawal, the time, precautions necessary for completing the questionnaire, the contents of the questionnaire, and confidentiality. Data were collected from May 5 to May 30, 2022, and the participants were asked to self-complete the questionnaire. The approximate completion time was 15 minutes, and a reward valued at 4,500 Korean won was provided to all participants upon completion of the questionnaire to conclude their participation.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konyang University (IRB No. 2022-03-005-002). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before study initiation. Participant anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed. Also, this study complied the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing in the Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research.20)

Instrument verification

The data collected to verify the validity and reliability of the developed instrument were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Item analysis, exploratory factor analysis, convergent validity, and discriminant validity were used to verify the construct validity of the instrument. Cronbach's α was used to verify the instrument’s reliability.

RESULTS

Instrument Development

Instrument factors derived from the literature review and FGI

We examined questions used in the measurement of infection control of emerging infectious diseases,21) practices related to novel influenza,13) and COVID-19 infection prevention and control behaviors,22,23) as well as the standards presented by the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention10) and factors based on the transmission route. The integration of the construct factors derived from the literature review and FGI resulted in 39 questions, including the following 12 factors: infection risk assessment and screening, hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, personal protective equipment (PPE), patient placement, caregiver and visitor management, patient transfer and movement, equipment and environment management, medical waste disposal, colleagues’ training, patient education, and visitor education.

Expert investigation of the content validity and reflection of the preliminary survey results

The validity of the content evaluated by the eight experts ranged from 0.88 to 1.0 for each item, with >88% of the participants responding to all 39 questions with a score of three or higher. Reflecting the expert’s opinions, one question regarding the epidemiological relationship of the patient’s symptoms was added. After conducting a preliminary survey of 10 nurses with 40 questions, the terms used in six questions were modified.

Application of the Instrument

General participant characteristics

The general characteristics of the participants in the application of the developed instrument are listed in Table 1. Of the 199 participants, 178 (89.4%) were female, and 108 (54.3%) were aged between 20 and 29 years. The most common level of education was a bachelor’s degree (n=143; 71.9%), and more participants lived with their families (n=128; 64.3%) than those who did not. Slightly more nurses worked at acute care hospitals (n=110; 55.3%) than those at long-term care hospitals (n=9; 44.7%). The most common position was “general nurse” (n=176; 88.4%), and most participants worked in general wards (n=145; 72.9%). Most had 1–3 years of clinical experience (n=48; 24.1%), followed by 47 with 5–10 years of experience (23.6%). The most common duration of experience in the current department was <1 year (n=63; 31.7%), followed by 1–3 years (n=54; 27.1%). One hundred and eighty-five participants (93.0%) reported having experienced caring for patients with confirmed novel respiratory infectious diseases and 188 (94.5%) reported having experienced caring for patients suspected of having contracted an emerging respiratory infectious disease. In terms of receiving infection control education in the past year, 186 participants (93.5%) responded “yes.” Regarding whether infection control education “helps to practice infection-preventive behaviors when treating patients with confirmed or suspected emerging respiratory infectious diseases,” most responded “yes” (n=98, 49.3%), while 56 (28.1%) responded “neutral” (Table 1).

Verification of the construct validity

Item analysis: To verify the instrument, the mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of the 40 items were measured. The mean score for each item was 3.57±0.62. The item with the lowest mean was #14 (“I always wear a mask when within 1–2 m of a patient with respiratory symptoms”), while the item with the highest mean was #7 (“I practice hand hygiene after being exposed to or highly likely to be exposed to patients’ blood, body fluids, secretions, excrements, and mucous membranes, damaged skin, or actions with a high risk of exposure”). Evaluation of the normality of the response data revealed that the absolute value of skewness represented good normality. The Pearson correlation coefficients to determine the correlation of the total number of items satisfied the requirement of 0.30 or higher and ensured the suitability for conducting exploratory factor analysis (Table 2).

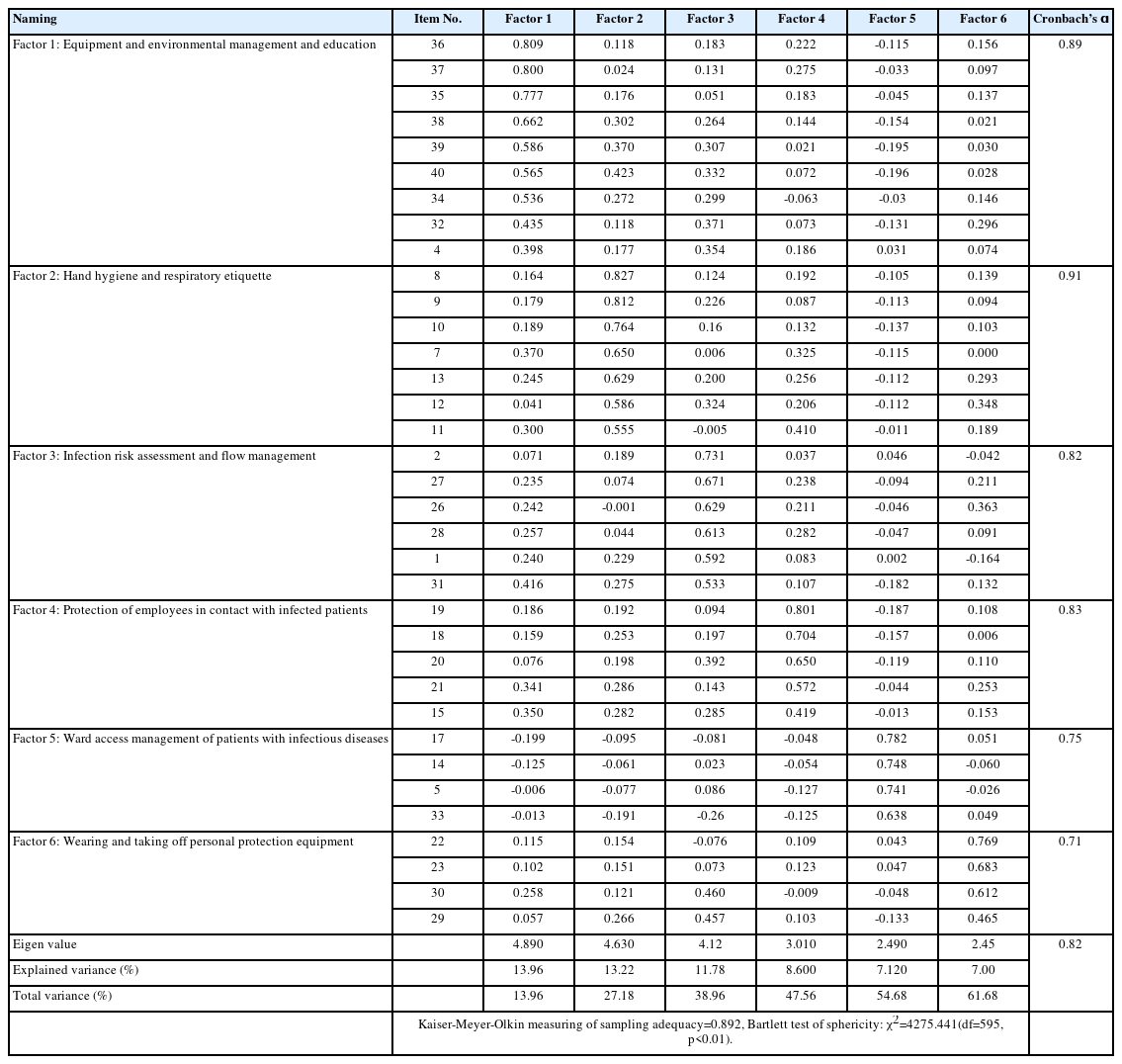

Exploratory factor analysis: We performed exploratory factor analysis to verify the instrument’s validity. After performing the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test and Bartlett test of sphericity to evaluate the appropriateness of the factor analysis, we performed a principal component factor analysis using the varimax rotation method. The factor analysis identified eight factors from the 40 items, and the cumulative variance of 65.1% demonstrated the appropriate explanatory power. However, items #24, #15, #16, #3, and #6 included in Factor 4 differed in content, as they were grouped into the same factor. Therefore, four questions were excluded, aside from item #15 (“I wear an N95 or KF94 mask when performing procedures [i.e., inhalation, airway intubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and bronchoscopy] in which aerosol is generated”), which experts considered essential for measuring the practice of infection-preventive activities. Among items #17, #14, #5, #25, and #33 included in Factor 6, item #25 was excluded because it differed in content from the other items included in Factor 6.

Six factors were identified by conducting a second factor analysis with 35 items, following which item #4 of Factor 1 was excluded due to its commonality of <0.4. Ultimately, eight items for Factor 1, seven for Factor 2, six for Factor 3, five for Factor 4, four for Factor 5, and four for Factor 6 were derived. The total variance explained by the 34 items was 61.68% (Table 3).

Convergent and discriminant validity: We used the construct reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) to verify the convergent validity of the instrument. The CR of the developed instrument was 0.71–0.91, where all factors satisfied the threshold of 0.70 or higher.24) Of the eight factors, Factors 1, 2, and 4 satisfied the AVE value of 0.50 or higher, while Factors 3, 5, and 6 did not (Table 4).

We measured the square of the correlation coefficient between the factors to verify the discriminant validity of the instrument.24) The results showed that the value was lower than the AVE of each factor of the developed instrument, except for Factors 1 and 3 and Factors 3 and 4 (Table 5).

Verification of the instrument’s reliability: We calculated Cronbach's α to verify the instrument’s reliability. Cronbach's α for the 34 items in the developed instrument was 0.82 overall, and ranged from 0.71–0.91 for each factor (Table 3).

Factor naming and instrument finalization: We selected 34 questions in the development of an instrument to measure nurses’ compliance with infection prevention activities and verified the validity and reliability of the measurement. The instrument consisted of six factors: Factor 1, equipment and environmental management and education, included eight items (#36, #37, #35, #38, #39, #40, #34, and #32); Factor 2, hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette, included seven items (#8, #9, #10, #7, #13, #12, and #11); Factor 3, infection risk assessment and flow management, included six items (#2, #27, #26, #28, #1, and #31); Factor 4, protection of employees in contact with infected patients, included five items (#19, #18, #20, #21, and #15); Factor 5, ward access management of patients with infectious diseases, included four items (#17, #14, #5, and #33); and Factor 6, wearing and removing PPE, included four items (#22, #23, #30, and #29). The score ranged from 35 to 140, with higher scores indicating more frequent infection-preventive behaviors.

DISCUSSION

The validation of the reliability and validity of the developed instrument to measure nurses’ compliance with infection-prevention activities against emerging respiratory infectious diseases derived six factors consisting of a total of 34 items, as follows: equipment and environmental management and education (eight items), hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette (seven items), infection risk assessment and flow management (six items), protection of employees in contact with infected patients (five items), ward access management of patients with infectious diseases (four items), and PPE wearing and removal (four items).

Factor 1, equipment and environmental management and education, had an explanatory power of 13.96%. It comprised eight questions, including medical waste, linen, reusable products, environmental surface management, and the education of patients, caregivers, and colleagues. In contrast to measures such as hand washing, cough etiquette, use of face masks, and social distancing identified by Jung and Hong,17) which examined COVID-19 infection-preventive practices in the general public, equipment and environmental management were derived as the main infection prevention activity compliance against emerging respiratory infectious diseases in this study of nurses. Specifically, in the case of emerging respiratory infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, the droplets released from a person's respiratory tract can contaminate environmental surfaces25); thus, the management of these surfaces is an increasingly important infection-preventive measure.

Factor 1 included three questions regarding nurses’ provision of information and educating communicative patients, caregivers, and colleagues. The agents who execute standard and transmission-based precautions are not limited to hospital staff, including nurses.10) Specifically, a standard precaution is a concept in which patients, staff, caregivers, and visitors in a healthcare facility recognize the risk of infection on their own and practice cautionary guidelines. Therefore, educating patients, caregivers, and colleagues is crucial for preventing the infection of nurses with emerging respiratory infectious diseases. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare facilities have restricted visitors; however, as they allow resident caregivers to care for patients, infection prevention education for caregivers, such as hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, and the use of face masks, is increasingly emphasized.26) In addition, as government guidelines frequently change with the rapidly fluctuating trends of the pandemic, the education of nurses, especially those who educate and inform their peers, is a major component of infection prevention activity compliance in emerging respiratory infectious diseases.

Factor 2, hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette, had an explanatory power of 13.22% and comprised seven questions, including four questions related to hand hygiene and three questions related to respiratory etiquette. Hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette are elements of the concept of standard precautions, which were also included as the primary concepts in the instruments of prior studies.17,25,27) Although the standard precautions include hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette, separately as an independent factor,10) this study grouped them as a single factor of preventive action against emerging respiratory infectious diseases because of the nature of the hand-mediated transmission of respiratory droplets that cause respiratory infectious diseases.

Factor 3, infection risk assessment, and flow management, had an explanatory power of 11.78% and comprised six questions, including identifying the clinical symptoms of patients, caregivers, and visitors and history of contact with a confirmed patient; logging entries; social distancing of 1–2 m; minimizing patient transfers and providing information to receiving departments; and limiting visitation. Unlike previous studies that measured the clinical symptoms of COVID-19 in terms of knowledge,28) the present study derived the risk of infection, clinical symptoms, and transmission route as the primary infection prevention activity in evaluating nurse compliance. Nurse assessment of infection risk and implementing appropriate isolation precautions according to the degree of infection risk are essential infection-preventive behaviors for preventing the spread of emerging respiratory infectious diseases.

Factor 4, protection of employees in contact with infected people, had an explanatory power of 11.78% and included five questions related to the selection of gowns, masks, goggles, and face shields, as well as precautions when putting on PPE. As presented in Factor 4, most prior studies10,18,19) also include PPE as a primary component of infection prevention against novel respiratory infectious diseases. Notably, the size of respiratory droplets produced during aerosol-generating procedures is <5 μm, with a very high risk of such droplets spreading with the flow of air.22) Therefore, the use of PPE, including high-efficiency filter masks, is an imperative strategy for preventing novel respiratory infections.

Factor 5, ward access management of patients with infectious diseases, had an explanatory power of 7.12% and comprised four questions, including hand hygiene of nurses before entering a patient’s room and coming in contact with patients with infectious diseases, wearing gloves, using masks, and disinfecting the environmental surfaces of isolation rooms. Factor 5 also included the elements of contact and droplet precautions of the transmission-based precautions.8) Viruses that cause emerging respiratory infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, are mainly transmitted through droplets. However, they are likely to aerosolize in areas with poor ventilation or insufficient environmental surface disinfection, or during procedures that produce aerosols such as suction28); thus, the implementation of airborne precautions is needed in such situations. The elements of airborne precautions were not constructed into a factor in this study, as the participants did not have ample experience in nursing confirmed patients with severe enough symptoms to undergo aerosol-generating procedures. Future studies should include participants who have experienced nursing patients with novel respiratory infections in a variety of situations.

Factor 6, wearing and removing PPE, had an explanatory power of 7.00%. Factor 6 comprised four questions, including the order in which PPE was put on and removed, the wearing of PPE for patient transfers, and providing hand hygiene and PPE to visitors. Many unknown aspects of emerging respiratory infectious diseases remain unknown, such as the pattern of occurrence and mutation of causative pathogens. Therefore, observing the order of wearing and removing PPE and treating patient blood, bodily fluids, secretions, and excrement as sources of infection, regardless of the diagnosis of an infectious disease10) are important preventive measures. Hand hygiene was required after the removal of each PPE item. Specifically, it is imperative to perform hand hygiene before touching the face, eyes, nose, and mouth, which are highly vulnerable to pathogen invasion.29)

This study developed an instrument with stable validity and reliability through a literature review, an FGI with nurses with experience in responding to emerging respiratory infectious diseases, and exploratory factor analysis. Compliance with infection prevention activity compliance against emerging respiratory infectious diseases could be accurately measured because the instrument was developed based on the experience of nurses who had treated patients with emerging respiratory infectious diseases at clinical sites, including long-term care hospitals. However, one limitation is that the instrument does not cover all infectious diseases, although it reflects preventive measures against respiratory infectious disease, as it was developed in the context of COVID-19. In addition, limitations may exist in measuring compliance with infection prevention activities against emerging infectious respiratory diseases among nurses caring for patients in other locations, such as children's hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, and outpatient clinics. The present study mainly targeted acute and long-term care hospitals where adult and older adult patients were hospitalized. However, this instrument can be validated, modified, and supplemented by repeatedly applying it to studies that target nurses working at various sites.

The developed instrument will allow the identification of nurses’ level of infection prevention activity compliance with novel respiratory infectious diseases. We further recommend the development of education and training programs promoting this compliance and the utilization of the developed instrument to evaluate their effectiveness.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The researchers claim no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This paper was supported by the Konyang University Research Fund in 2021.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: SYJ; Data curation: MSS, SYJ; Funding acquisition: HJJ, MSS, SYJ; Investigation: HJJ; Methodology: HJJ; Project administration: HJJ, MSS, SYJ; Supervision, HJJ, MSS, SYJ; Writing-original draft, HJJ, MSS, SYJ; Writing-review & editing, HJJ.