Gastric Cancer in Older Patients: A Retrospective Study and Literature Review

Article information

Abstract

Background

With increasing life expectancy, the incidence of gastric cancer (GC) in older adults is increasing. This study analyzed differences in GC characteristics according to age and sex among patients who underwent surgical treatment for GC.

Methods

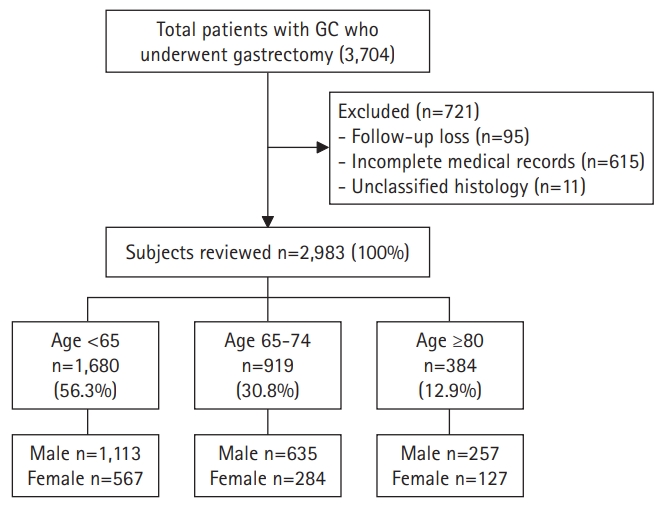

A total of 2,983 patients diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma who underwent surgical treatment at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between 2003 and 2017 were classified into three groups: I (<65 years, n=1,680), II (60–74 years, n=919), and III (≥75 years, n=384). We compared the baseline clinical characteristics, pathological characteristics of the tumor, overall and GC-specific survival rates, and associated risk factors between the groups.

Results

Cancer of the distal third of the stomach (p<0.001), with intestinal-type histology (p<0.001), and with p53 overexpression (p=0.004) were more common in groups II and III than in group I, and the proportion of intestinal-type GC increased with age. The cancer type, lymph node metastasis, and cancer stage did not differ significantly. In terms of overall survival, survival decreased with increasing age (p<0.001), but this difference decreased significantly for GC-specific survival. Cox multivariate analyses revealed age, histologic type (diffuse or mixed type), and advanced cancer stage (p=0.002, 0.001, and <0.001, respectively) as risk factors for GC-related mortality.

Conclusion

Age itself was found to be one of the most important prognostic factors for overall and disease-specific survival in elderly GC patients, along with cancer stage.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common cancer and third most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.1) The incidence and prevalence of GC are high, particularly in East Asia, including in South Korea. While a large-scale nation-led endoscopy surveillance program to reduce GC-related deaths in South Korea has shown considerable effect,2) GC-related death still ranked 4th among carcinomas in 2020.3) In addition, its peak incidence occurs in the seventh decade of life; thus, the incidence of GC is expected to increase owing to the extended lifespan of the general population.4) Furthermore, there are no specific surveillance and treatment guidelines for older age groups, making it difficult to determine the upper limit of the age of surveillance, diagnostic examinations, and invasive treatments. Another potential factor increasing the risk of GC-related death is the reluctance of both older adult patients and medical experts to receive or perform standard examinations or treatments due to the risk of complications.5) The present study compared the characteristics of GC in older patients to those of younger patients with GC and to those of previous studies to help guide treatment for GC in older adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Initially, we selected 3,074 patients aged >18 years from a prospective surgical cohort of patients who were diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma and underwent surgical treatment at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH) between 2003 and 2017. We previously reported the effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment, p53 overexpression, and incidence of metachronous GC in this cohort.6,7) The following patients were excluded from the present study: those with incomplete medical records or unclassified histology, those who were lost to follow-up, those with a prior history of other cancers at the time of diagnosis, and those with other inoperable diseases. Finally, we included 2,983 patients in the analysis and classified them into three groups based on age: I (young, age <65 years, n=1,680), II (early old, age 60–74 years, n=919), and III (old, age ≥75 years, n=384) (Fig. 1). We defined old age as 65 years and older based on previously published studies. We also conducted additional analysis of patients ≥75 years of age. Since the average life expectancy is increasing, so we tried to assess the difference between the relatively young and super-aged older adults. Data such as sex, age, death (including causes of death), histologic type of cancer, and social history such as alcohol consumption, smoking, and family history of GC were collected from surgical and medical records and reviewed using the Clinical Data Warehouse. Family history was defined as at least one patient with GC among first-degree relatives. Otherwise, the patient was categorized as having no relevant family history. The presence of atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia was confirmed by histological examination based on the modified Sydney Classification for endoscopic biopsy in the antrum and body, which was performed at the time of cancer diagnosis. If one or more of the three preoperative tests for H. pylori (urease breath test, rapid urease test, or histology) showed a positive result, the patient was considered H. pylori-positive; otherwise, they were categorized as H. pylori-negative. We verified the dates and causes of death of the enrolled patients through cross-review of data from the National Statistical Office.

Statistical Analysis

The outcomes were overall and gastric cancer-specific survival. Student t-test and chi-square test were used for comparisons between groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards analyses were used to identify risk factors, and variables with p<0.2 in the univariate analyses were used as covariates in the multivariate analysis. The Kaplan-Meier estimator method and log-rank tests were used to compare survival. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Ethical Considerations

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (No. B-1902–523-107) and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 03978481). As this study was performed retrospectively, the IRB permitted a waiver of informed consent. All authors had access to the study data and approved the final manuscript.

RESULTS

Baseline Clinicopathological Characteristics

The baseline clinicopathological features of the patients are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Of the 2,983 patients, 1,680 were aged <65 years (group I), 919 were aged 65–74 years (group II), and 384 were aged ≥75 years (group III). A higher proportion of younger patients reported alcohol consumption and smoking (p<0.001 for both drinking history and smoking history), as well as H. pylori infection (p<0.001). Intestinal metaplasia was more common in group II than in the other groups (p=0.006). Sex and atrophic gastritis did not differ significantly between the groups (sex, p=0.333; atrophic gastritis, p=0.074) (Table 1). Cancer of the gastric body and diffuse-type histology were more common in younger patients, and cancer of the gastric antrum and intestinal-type histology increased with age (tumor location p<0.001 and histologic type p<0.001, respectively). Lymph node metastasis, cancer stage, and surgical methods did not differ significantly according to age (node metastasis, p<0.779; TNM stage, p=0.471; surgical method, p=0.504). p53 overexpression was more common in groups II and III than in group I (p=0.004) (Table 2). The results of additional analysis according to age and sex are provided in Supplementary Table S1. While females in groups II and III had more advanced cancer and lymph node metastasis than in males in groups II and III, the differences were not statistically significant. Comparisons according to tumor location showed that the incidences of cardia cancers increased with age, and associated risk factors included the presence of intestinal metaplasia and p53 overexpression. The detailed features of cardia and non-cardia cancers are described in Supplementary Table S2.

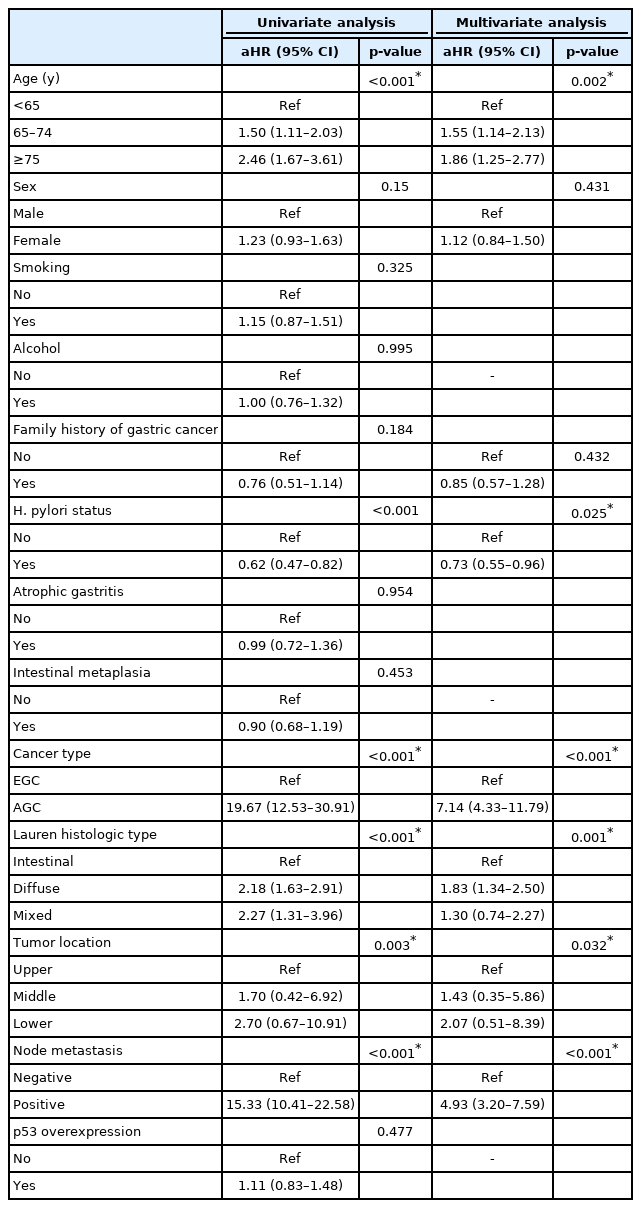

Risk Factors for GC-Related Death

Cox univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to determine the risk factors for GC-related death (Table 3). In univariate analyses, older age, female sex, lack of a family history of GC, H. pylori negativity, advanced-stage cancer, diffuse or mixed type histology, middle- or lower-third tumor location, and lymph node metastasis were identified as potential risk factors. In multivariate analyses, the risk factors for GC-related death were old age, H. pylori negativity, advanced-stage cancer, diffuse or mixed type histology, middle- or lower-third tumor location, and lymph node metastasis (age, p=0.002; H. pylori status, p=0.025; cancer type, p<0.001; histologic type, p=0.001; tumor location, p=0.032; node metastasis, p<0.001, respectively).

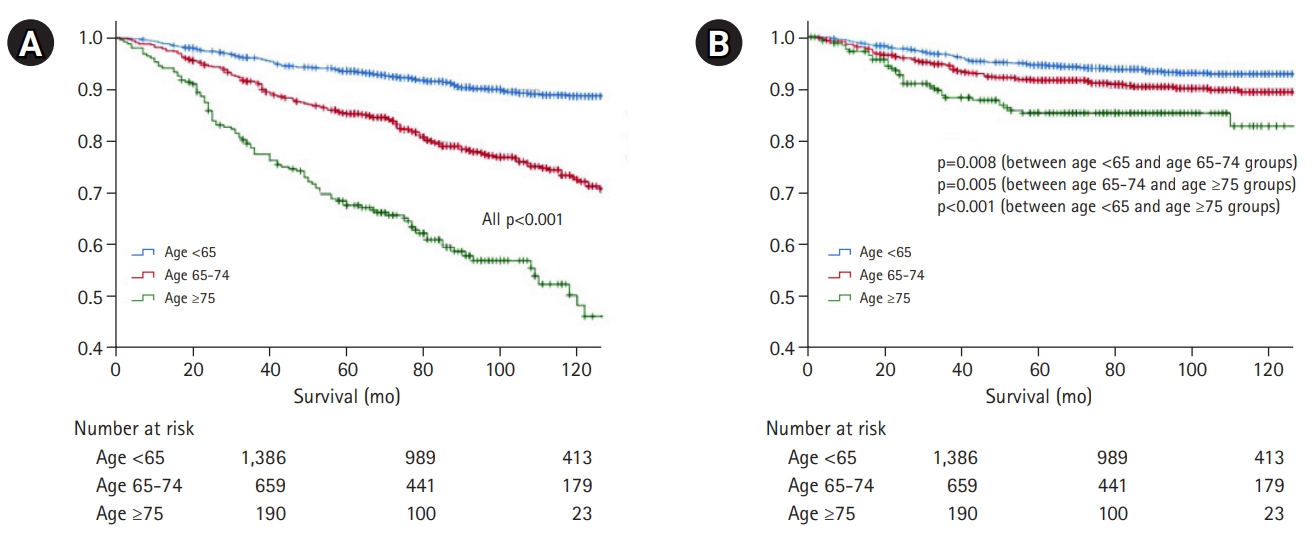

Overall and Cancer-Specific Survival

Overall survival in the three groups is shown in Fig. 2. In terms of overall survival, we observed a statistically significant difference according to the age, with survival decreasing with increasing age (p<0.001) (Fig. 2A). However, in GC-specific survival, the difference according to age decreased compared to that for overall survival, although the difference remained statistically significant (p=0.008 for group I vs. II; p=0.005 for group II vs. III; and p<0.001 for group I vs. III) (Fig. 2B).

(A) Overall survival and (B) gastric cancer-specific survival according to age. Overall survival differs significantly with age, with survival decreasing with increasing age (p<0.001). However, the difference in gastric cancer-specific survival according to age is lower than that for overall survival, although the difference remains significant (p=0.008 for group I vs. II; p=0.005 for group II vs. III; p<0.001 for group I vs. III).

The results of additional stratification analysis according to cancer stage and sex are shown in Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2. In the stratification analysis according to GC stage, we observed age-specific differences in overall survival (Supplementary Fig. S1) compared to GC-specific survival (Supplementary Fig. S2). In particular, the differences in overall and GC-specific survival depending on age were significant in stages I and II (Supplementary Figs. S1A, S1B, S2A) but not in stages III or IV. We observed female advantage in overall survival in each age group (Supplementary Fig. S3). In contrast, men showed advantage in GC-specific survival in all age groups (Supplementary Fig. S4).

In the analyses of survival and causes of death, the GC-related mortality rates increased with age. However, deaths from diseases other than GC more significantly increased with age. The older adult groups showed more deaths from cerebrovascular and pulmonary diseases, sepsis, and multiorgan failure, compared to the younger patient group (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that among older patients, GC was more prevalent in the lower third of the stomach; furthermore, they also had a high rate of intestinal-type histology. Lymph node metastasis and cancer stage did not differ significantly according to age. While we observed a significant difference in overall survival according to the age at which survival decreased with increasing age, those differences decreased in GC-specific survival, suggesting that not only cancer itself but also other factors, such as comorbidities, combine to affect the prognosis of older patients with GC. We observed female advantages in overall survival and male advantages in GC-specific survival among all age groups.

Previous studies also described the characteristics of GC in older adult patients. Clinically, GC in this population occurs predominantly in men, compared to GC occurring in younger patients. Endoscopically, GC is antral dominant and often visually depressed (II-c in early GC and Borrmann type III in advanced GC). Histologically, intestinal-type well-differentiated cancers are common while diffuse-type ones are rare, consistent with our observations. Approximately 8%–15% of cases present synchronous lesions at the time of diagnosis, likely due to the multifocal carcinogenic foci of atrophic gastritis and internal metaplasia. Hematological metastasis to the liver through the portal vein is common, whereas peritoneal seeding or lymph node metastasis is relatively rare compared to GC in younger patients.8-10)

Several small-scale studies have reported on the treatment of GC in older adult patients, and most have reported similar results as that seen for GC in young patients. First, in the case of surgical treatment, very old adults (≥80 years) showed more postoperative pulmonary complications compared to older adult patients aged 65–79 years; however, there was no difference in mortality.11) A study of GC patients over the age of 85, 81 and 89 patients who received conservative care and who underwent surgery, respectively, reported that surgery improved GC prognosis.12) Suematsu et al.13) reported similar overall postoperative complication and survival rates after total gastrectomy, even in patients >75 years of age. Some studies have reported no statistically significant differences in complications according to age after gastrectomy and that surgical treatment is tolerable in old age.14-16) As it is often difficult to actively administer chemotherapy due to the presence of underlying diseases or organ dysfunction in older adult patients, Wakahara et al.17) recommended active treatment such as surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy, if possible, and reported improved survival in older adult patients with advanced GC who received adjuvant chemotherapy for >3 months. Meanwhile, another study reported that surgery alone improved survival compared to conservative treatment in older adults patients who were ineligible to receive chemotherapy.18)

However, careful decision-making is needed for the treatment of older adult patients with GC. First, Zhou et al.19) reported lower albumin levels, higher ASA (American Society of Anesthesiology) grades, comorbidities, tumors located in the upper third of the stomach, and advanced TNM stages in older adult patients with GC. Moreover, complications tended to increase with age, especially respiratory problems, and severe complications increased significantly in the old-old (≥80 years); therefore, caution is needed in determining the treatment policy in extremely old patients. A previous study reported similar short-term outcomes according to age but inferior long-term prognosis in older adult patients and those with advanced cancer; therefore, the indications for surgery in older adult patients with advanced cancer require careful consideration.20) Lim et al.4) analyzed 1,107 patients who underwent surgery for GC between 2005 and 2009 by classifying them into three age groups (<65, 65–74, and ≥75 years) and observed were more advanced diseases and synchronous cancers in the older groups, suggesting the need for caution before determining the treatment method in these patients.

As mentioned above, we observed statistically significant differences in overall survival according to the age at which survival decreased as age increased; however, these differences were smaller for GC-specific survival, suggesting that not only the cancer itself but also other factors, such as comorbidities, may together affect the prognosis of older adult patients with GC. Factors other than age are more important in determining the prognosis of patients with GC. Tatli et al.21) suggested that the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score was more important than age in determining treatment methods. Other researchers proposed comorbidities and nutritional status as prognostic factors in older adult patients with GC as poor nutritional status and multiple comorbidities were risk factors for death.22) An analysis of 1,658 patients diagnosed with GC based on the age of 45 years, GC in older patients showed male predominance, less aggressive features and less advanced stage than those in younger patients. And precancerous lesions including atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, overexpression of p53 and and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and microsatellite instability (MSI) were more common in older patients than in younger patients. Moreover, tumors with p53 mutation, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) overexpression, and microsatellite instability (MSI) are more often observed in older adult patients. However, despite these clinical and pathological differences, cancer stage was the prognostic factor that most significantly affected patient survival.23) In addition, in the present study, overall survival was superior in women, while GC-specific survival was superior in men, especially in the 65–74-year age group. Additional analyses revealed trends of higher lymph node positivity and advanced cancer trends in women in that age group, although the differences were not statistically significant. While there remains uncertainty in the prognosis of GC according to sex, studies have reported a worse prognosis in women with advanced stomach cancer; thus, sex is also an important factor to consider in the treatment of older adult patients with GC.24)

Thus, active treatments such as surgery or chemotherapy can be considered even in older adult patients, and it is not reasonable to determine a treatment plan based on age alone. However, additional indicators should be considered in very old patients as we observed a significant increase in mortality. A previous study utilizing various scoring systems, including the ASA score, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and Glasgow Prognostic Score, reported that the scores of these indexes tend to be low in older adult patients.13) Poh and Teo25) proposed that the Edmonton Frailty Scale (EFS) might also be useful as a screening tool before elective cancer surgery in older adult patients. Our results suggested that these indicators should be used in patients >75 years of age in sufficiently good general health condition before active treatments, such as surgery. In addition, active implementation of strategies of primary prevention, including H. pylori eradication, and secondary prevention, such as endoscopic surveillance, are needed to prevent GC. A recent Japanese study reported that while GC-related deaths in Japan declined overall, those in older adults did not, which the authors attributed to the fact that many older adults did not undergo regular screening.5) In addition, if available, endoscopic treatment of early cancer should be considered as the risk of complications has decreased due to the advancement of examination techniques; thus, endoscopic treatment is less invasive than surgery or systemic chemotherapy.

Our study had several limitations. First, there was potential bias due to its retrospective design. For instance, we could not determine all patient comorbidities, which could probably affect the overall survival results of patients; thus, there were some older patients in whom the cause of death was not clear. However, we attempted to analyze all causes of death in the medical and surgical cohorts. Second, as we analyzed only patients who underwent surgery, we could not compare our findings to patients who did not receive curative treatment or other treatments such as chemotherapy. Third, we could not confirm the history of H. pylori eradication despite H. pylori being a well-known risk factor for GC. As this was a retrospective study, the results of all three H. pylori tests and history of eradication treatment could not be confirmed in all patients. Further research is needed to determine the effect of H. pylori eradication on reducing GC incidence in older adult patients. Finally, as the 6th edition of the AJCC staging system was published in 2002, the 7th edition in 2010,26) and the 8th edition in 2016,27) we could not adopt a consistent edition of the AJCC cancer staging system due to the long patient enrollment period. Despite these limitations, the number of patients with data from long-term follow-up in our study was relatively large and the histological type of cancer was accurately confirmed through surgical methods. Moreover, we performed additional subgroup analyses according to age (early old and old) and sex to observe the changes in overall and GC-specific survival.

In conclusion, cancer of the distal third of the stomach and intestinal-type histology were more commonly seen in older adults with GC, and the proportion of intestinal-type GC increased with age. We observed a statistically significant difference in overall survival according to the age at which survival decreased as age increased; however, this difference decreased in GC-specific survival. The risk factors for GC-related mortality were age, histological type, and advanced cancer stage. While age was not the most important factor in determining the prognosis of GC, it remains one of the most important prognostic factors, along with cancer stage. Care should be taken when deciding on surgery for older adult patients with GC, considering their poorer survival outcomes. Various prognostic indicators such as age, sex, nutritional status, comorbidities, and performance status score should be used to consider patient functional, social, and emotional aspects.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.21.0144.

Pathological characteristics of each group according to sex

Comparison of characteristics between those with cardia and non-cardia cancers

Overall survival according to cancer stage in each age group: (A) stage I, (B) stage II, (C) stage III, and (D) stage IV. Overall survival (p<0.001 in stage I and II; p=0.080 in stage III; p=0.035 in stage IV; respectively) differs significantly among age groups.

Gastric cancer-specific survival according to cancer stage in each age group: (A) stage I, (B) stage II, (C) stage III, and (D) stage IV. The statistical significances are reduced for GC-specific survival, with a smaller difference compared to the overall survival (p<0.001, p=0.554, p=0.210, and p=0.112 for stages I–IV, respectively).

Overall survival according to sex in each age group: (A) I (young: age <65 years), (B) II (early-old: age 60–74 years), (C) III (old: age ≥75 years). Women show a non-significant advantage in overall survival in each age group (p=0.130, p=0.060, and p=0.081 for groups I–III, respectively).

Gastric cancer-specific survival according to sex in each age group: (A) I (young: age <65 years), (B) II (early-old: age 60–74 years), (C) III (old: age ≥75 years). Men showed GC-specific survival advantages all age groups (p=0.867, p=0.032, and p=0.793 in groups I–III, respectively).

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The researchers claim no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital Research Fund (No. 02-2020-041).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization, NK; Data curation, YC, NK; Funding acquisition, NK; Supervision, DHL; Writing-original draft, YC, NK; Writing-review & editing, KWK, HHJ, JP, HY, CMS, YSP, DHL.