Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research as a Space of for Developing Research Ideas into Better Clinical Practices for Older Adults in Emerging Countries

Article information

Hypotheses in large-scale clinical trials with high levels of evidence that affect clinical care guidelines are rarely developed from scratch. Rather, hypotheses from numerous small studies that tinker with processes from clinical experience or from modest research ideas are developed, tested, and discarded at varying stages of research and evidence levels.1) During these processes, some ideas attract attention from academic societies, policymakers, or industries and survive for inclusion in larger trials.

As both clinicians and researchers in an emerging country, we sometimes feel frustrated at the difficulties in initiating research on our older population. Government-based funding sources commonly require existing clinical evidence on research topics, usually from high-profile journals; however, publication in these high-profile journals from developed countries is sometimes difficult in the case of small or idea-generating studies performed specifically in older adults in emerging countries. Therefore, researchers sometimes feel that acquiring research support for understudied clinical topics is a chicken-and-egg problem. Even worse, some Asian countries evaluate researchers’ performance on the basis of their record of publication in high-impact journals,2) giving minimal impetus to researchers submitting their articles to journals from emerging countries. Consequently, researchers are prone to conducting studies with ideas and designs that meet the interests of the readership of journals from Western countries. This focus may decrease the clinical relevance of the research findings in their own populations.3) Consequently, we have noted that many problems that we face in fragmented clinical practices for our patients remain in status quo and fail to be included in viable research agendas.4)

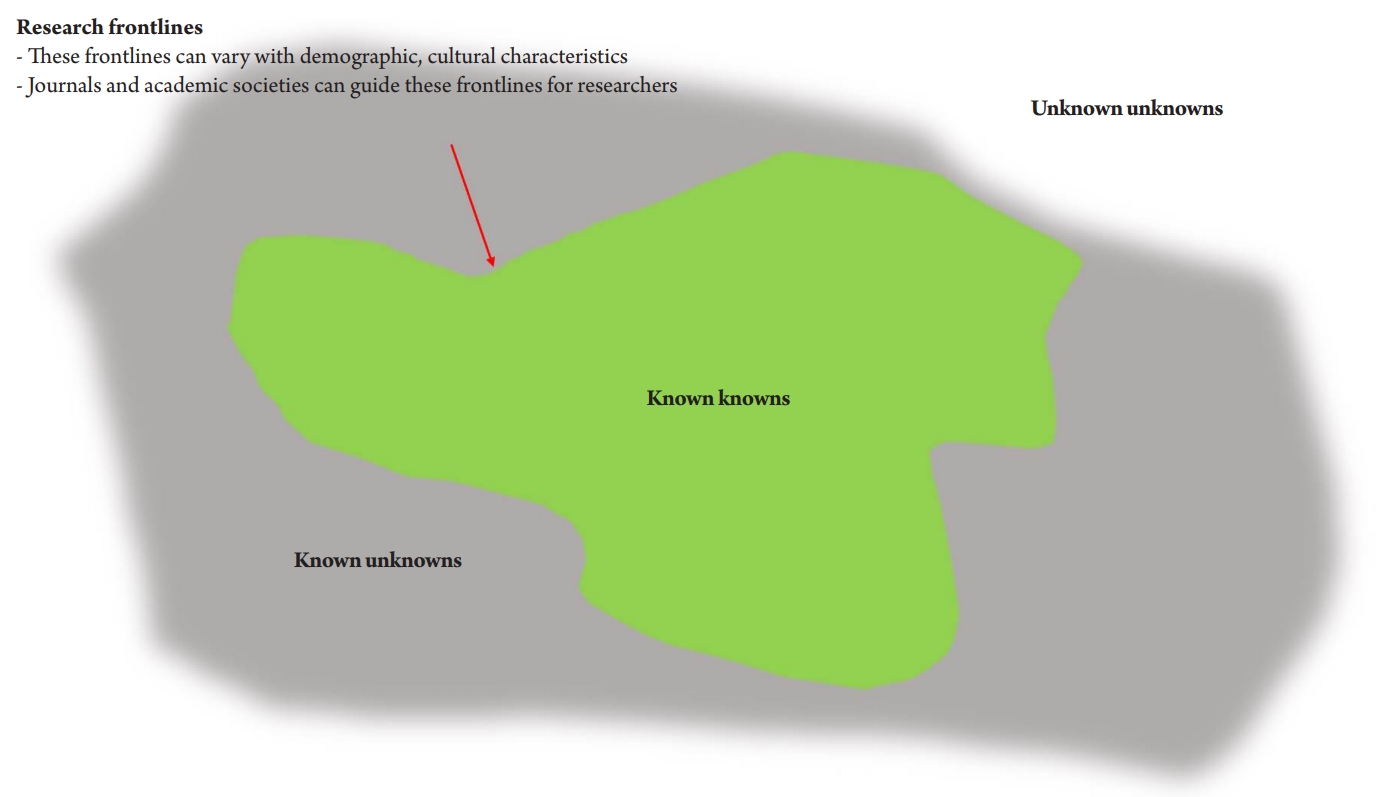

However, the research topographies of known, known-unknown, and unknown-unknown scientific knowledge differ by country because of varying socio-demographic and cultural characteristics and care delivery systems (Fig. 1). For example, the socio-economic importance of frailty and functional impairment might be more evident in countries with high aging population ratios, whereas these issues are less obvious in countries with populations of lower age groups. With these differences, emerging nations may have to repeatedly establish clinical evidence on varying topics related to population aging that are already well-established in developed countries. Consequently, journals with population-specific readership are needed in emerging countries experiencing unprecedented demographic aging, with distinct population characteristics from those in developed countries with more established care systems for their older population. Furthermore, we need journals with editorial perspectives that support the tinkering processes of research ideas that may eventually improve clinical practices for older populations.

To meet these unmet needs, our journal has been working with contributors and readers worldwide to become an easily accessible multidisciplinary journal for geriatrics and gerontology in emerging countries experiencing population aging at an unprecedented pace. In terms of advances in academic communication, we now celebrate that our journal is being indexed in Scopus, after our inclusion in the Emerging Scientific Citation Index in 2018. Furthermore, scholars from emerging countries, including Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and Hong Kong, with vast research experience in the field, have joined our journal as editors.

To bolster the development of research ideas for older populations in our region, our journal is eager to receive research on population- or region-specific issues, with varying levels of evidence, including qualitative research such as narrative studies, small-scale case series, or proof-of-concept pilot studies. For example, a study from Japan by Hattori et al.5) describing cases of successful removal of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes in patients with advanced dementia reflects unique cultural characteristics in East Asian countries regarding the importance of providing oral or enteral nutrition even to terminally frail patients. Similarly, a study from Brunei by Akbar et al.6) reports the perspectives of healthcare providers, including the cultural characteristics of Asian countries in terms of hierarchies among professionals and mood or pain status in less-expressive patients. Regarding the population-specific research topography of geriatrics and gerontology, we will publish more reviews and opinions to provide research perspectives, serving as signposts for planning studies.7) We welcome active input from varying countries, in addition to current contributions from small interest groups within the Korean Geriatrics Society.

As most countries have insufficient geriatric care workforces to serve the substantial healthcare demands of their rapidly aging populations, expanding geriatric concepts will be essential, as already observed in developed countries. To expand the concept of geriatrics to non-geriatric specialists and students, we also call for research on strategies for interprofessional geriatric education and geriatric teaching programs for medical students. Sharing of country-specific experiences and current problems in developing geriatric education systems will allow dialectic evolution of each country’s system to improve efficiency.8) Moreover, societies are in the processes of developing and advancing optimal care delivery systems for older adults with varying functional capacities and multimorbidity that are currently lacking in most countries. In these processes, clinicians, researchers, and policymakers can learn and brainstorm by sharing their country’s history, current situation, and plans for geriatric care. In 2018 and 2019, we received input from diverse countries, including Australia,9) Taiwan,10) and Korea.11) We hope to soon offer more papers on care model development in older populations.

In the next decade, most emerging countries are expected to experience increasing demands for their aging populations, with shortages of geriatric workforces and ailing healthcare systems that were designed for the 20th century. Our journal will serve as an arena for brainstorming among emerging nations worldwide to bring research ideas into practice by providing evidence in these aging populations.

Notes

The authors claim no conflicts of interest.